Art World

The Art of Recovery: How a Radical Public Art Experiment Is Reshaping Sicily 50 Years After a Devastating Earthquake

Organizers hope that the rebuilt town of Gibellina will be Italy's answer to Marfa.

Organizers hope that the rebuilt town of Gibellina will be Italy's answer to Marfa.

Patricia Zohn

On a recent day this summer, I left the colorful, urban interventions and crowded revelries of Manifesta 12 in Palermo, Sicily, and descended into the rural, arid Belice Valley. I was accompanied by Zeno Franchini of the Fondazione Manifesto, an advocacy group that leads tours of the region, which was devastated by the 1968 earthquake in Sicily. I joked that I had kidnapped the 29-year-old ex-Veronese who had taken his passion and can-do to the very southernmost regions of Italy, but in fact I found that violence was threaded throughout the story of this trauma.

More than the number of people who died (approximately 400), or the number rendered homeless (approximately 100,000), the earthquake exposed grave fissures in the socioeconomic and political fabric of one of Italy’s poorest regions—disparities that linger to this day.

While thousands of earthquake victims lived outside Gibellina, an isolated agricultural community, in two shanty towns with barebones infrastructure, in 1970, the National Institute of Social Housing in Rome, determined, after numerous plans for reconstruction were abandoned, to build an entirely new city, a Gibellina “Nuova,” for the victims at a site 11 miles from the ruins. The land for the new city was partially purchased from the Salvo cousins, two notorious, wealthy Mafia bosses who had worked behind the scenes for years as economic capos.

The urban plan resembled a butterfly with a central axis for services and housing in the “wings.” It was based on a model of cars and grand boulevards (with shades of Robert Moses), completely antithetical to the medieval central square plan of Gibellina “Antico.” Artist Nanda Vigo remembers how “cold and anonymous everything looked” in the original plan. Finally, construction of the new city began in 1971. But by 1979, scant progress had been made due to government corruption, the Mafia influence, and red tape, and victims were still living in dire conditions. That’s when Gibellina’s flamboyant, powerful gay Mayor, Ludovico Corrao, invited a number of leading Italian and German artists and architects to participate in a rescue mission.

Corrao, who was known to whisk into rooms of Roman bureaucrats with his colorful scarves and brash attitude, believed he could inspire a new utopian network of relations and exchanges through the arts, and that Sicily—and especially his beloved Gibellina—was the place to realize his “Mediterranean Dream.” Though there was no budget for art or culture, Corrao had already begged and borrowed to found the Orestiadi performance festival, just outside the ruins of Gibellina, with the help of performers like John Cage and Philip Glass. Emilio Isgrò, an artist and dramatist, described a wind-chilled night of 1983 “where artisans, sheep farmers, housewives, anti-Mafia judges and theater directors and personalities from all over Europe sat together to watch” his performance in the festival.

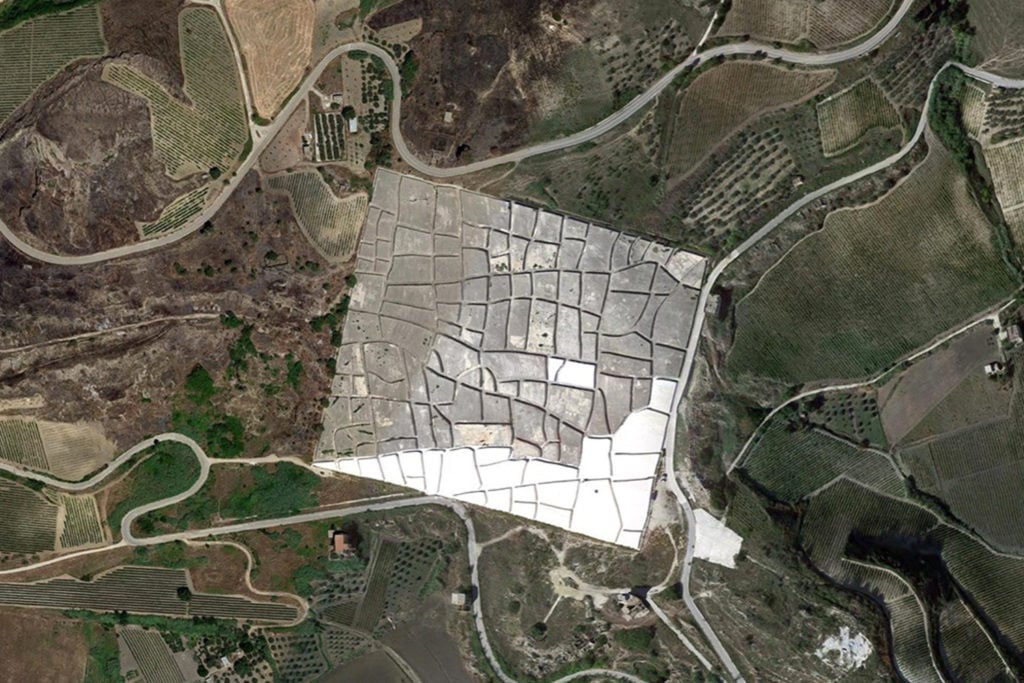

Artists began responding to the devastation, most famously Alberto Burri and his 1984 Grande Cretto, a blanket of white concrete laid over the destroyed town of Gibellina. But while such “Concrete Utopias” are now getting attention in museums, it was actually the concrete Utopian city of Gibellina Nuova that became an open-air laboratory for assessing the healing capabilities of public art. Today, 50 years since the earthquake struck, many look back on Corrao’s radical experiment in civic engagement, rehabilitation, and unification as a cautionary tale. But new efforts are now underway to realize a more pragmatic version of that utopian dream.

Alberto Burri, Cretto (1984–2016). © Fondazione Manifesto.

“The city needs to really become an Art Town,” says Alessandro La Grassa, president of the Center for Social and Economic Research of Southern Italy, the organizational heir to the early activist efforts. He envisions it as a place “where artists live or stay and where empty buildings and spaces start to find a new function. A city that becomes a sort of Mediterranean Atelier for Contemporary Art. We are trying to reignite Corrao’s dream after years of economic and social stagnation.”

Today the region is a symbol of hope. A newly revitalized combination of social activists, municipal agencies, educational institutions, and private support is finally bringing the unique art interventions of more than five decades in the Belice Valley—and especially the city of Gibellina—to the attention of a wider public. But to understand the enormous ambition of the current project, one must understand its complex history.

The tour stopped first at the small town of Poggioreale where Franchini and I are met outside a chain-link fence that protects the remarkably preserved ghost town by La Grassa. As we walk the main street past the ruins of a propped-up church, a school, and dwellings interspersed with tumbleweed, La Grassa describes it as “a town that resisted the heartbreak” (only three died here). Its haunting quality makes it easy to see why it has been used by Giuseppe Tornatore and others as a film location.

Ruins of Poggioreale. © Fondazione Manifesto.

Our second stop is Burri’s Grande Cretto, already on the radar of art cognoscenti. Burri, a master of the unconventional, was resistant to working in the new city and proposed instead to memorialize Gibellina Antico in its entirety. It’s impossible not to be awed by the enormous artistic, fiscal, and human energies poured along with the concrete, which covers the massive wound and honors the original footprint of the medieval city. Carrao pulled every string imaginable to get construction assistance—including a military airdrop—for the first phase of work in 1985.

But it’s arriving at the third stop on the tour, Gibellina Nuova, via a pristine new road from the Cretto that I more fully understand the ambition—and unintentional blind spots—of Corrao’s activists and artists.

When Carrao issued the call to invigorate the new city, they began to suggest projects to him. Franco Purini, who with his wife Laura Thermes designed the 1980 Casa del Farmacista, remembers he gave them the freedom to “propose necessary, experimental solutions” in consultation exclusively with him. Purini and Thermes were also behind the Sistema delle Piazze (1990), a new take on the town square.

We enter the town from a side street but there’s an immediate theatricality that makes me feel as if I’ve entered a de Chirico painting—in fact, the inspiration for Purini and Thermes. Many other framing devices and sky spaces designed to set off the architecture and monuments make Instagrammable moments appear at every turn.

Franco Purini and Laura Thermes, Sistema Delle Piazze (1990). © Fondazione Manifesto.

We pass Carmelo Cappello’s 1979 striking aluminum and concrete sundial Ritmi Spaziale, Pietro Consagra’s 1984 majestic but incomplete Teatro Frontale, as well as his soaring 1976 Meeting Hall, which now houses a small café, one of just two in the city. More than 76 Brutalist, postmodern, and more contemporary buildings and monuments were begun over five decades, many from elements that had survived the earthquake. Artist Nanda Vigo, who repurposed a fountain, an arch, and some pillars from the old town for her 1976 installations Tracce Antropomorfe, says, “everybody was free to choose location and materials. There were no restrictions. The only problem was the money, which of course was not there.” Corrao scraped together funding for some projects, but many of the works were ultimately donated by the artists.

Pietro Consagra, Meeting Hall (1976). © Fondazione Manifesto.

It’s not until I become conscious of the wide, deserted streets and squares that it becomes harder to reconcile Corrao’s vision with reality. A number of the artworks have degenerated or were never completed due to lack of funding. The priest whose congregation was intended to occupy architects Ludovico Quaroni and Luisa Aversa’s 1972 Chiesa Madre, which dominates the town like a 10th planet, felt he had not been properly consulted on the plans and never preached there—and then the roof collapsed.

The recorded folk songs that once issued from Alessandro Mendini’s Torre Civica (1987) were disorienting to the populace and now no longer sound. Salvatore Cuschera’s Scultura Sdralata (1992) was arbitrarily moved inside a school from its intended location. Giampaolo di Cocco’s submarine-inflected Animalia Grandi Naufragi (1993), has twice been vandalized. “I don’t know if it’s worth reconstructing another time,” he admits. “Art and architecture can make a place special but it must be continuously managed.”

Aside from the lack of funding for installation and upkeep, an underlying and more crippling problem emerged. Although some local artisans and craftsmen participated in the process, many victims, thrust into a new environment of wide boulevards and isolated works of art in which they had no stake, felt disoriented. “Sometimes the elders seemed lost in a metaphysical town ill-suited to their needs and habits,” says Cuschera.

La Grassa, whose wife grew up in an encampment adjacent to Gibellina, says, paradoxically, “Although things had been bleak in the shantytowns, there had been a strong sense of community due to the activist movement for reconstruction.” Far from their agricultural roots and traditions, already hampered by illiteracy and unemployment, many residents fled when they were left out of the decision making. This skepticism, alongside the government inefficiency and waste, derailed the outsized project. Thus housing and public corridors designed for up to 20,000 contain only approximately 4,000 inhabitants. Artist Emilio Isgrò came to understand that the “survival problems of the Gibellinese could not be resolved only by art.”

Igino Legnaghi, Ritmi Sismici (1984). © Fondazione Manifesto.

University of Palermo professor Federica Sibilia did an exhaustive study of Gibellina Nuova in 2016 and it’s the first time I’ve ever read of a whole town suffering from “depression” and an “identity crisis.”

But La Grassa defends Corrao. “Sometimes I try to imagine the efforts of this mayor in trying to work on every aspect of this astonishing plan,” he says. “He not only had to convince and ‘cuddle’ the artists and architects,” but he also had to find the money, confront the bureaucracy, and “stay as distant as he could from the Mafia.” In the end, Carrao was a visionary who was not equipped to oversee the long run. “Gibellina is a surreal place where tractors are parked in front of world-famous artworks,” La Grassa says. “It’s up to us and the new generation, who are now really beginning to look at their city in a new way, to complete the work.”

Luckily for Gibellina, La Grassa is a pragmatist with an abundance of patience who believes in consensus. His organization, the Center for Social and Economic Research, is collaborating with the municipality, the Fondazione Orestiadi (the theater and museum organization), the wine company Tenuti Orestiadi, and other local entities to reinvigorate this extraordinary city in which so much art investment has already been made.

Costas Varotsos, L’Infinito Della Memoria (1992). © Fondazione Manifesto.

La Grassa’s group has helped devise practical solutions in a “New Urban Plan.” When he was not able to attract interest from Italian foundations or philanthropists, he turned his attention to European funding and open calls. In 2016, the Center received an EU L.E.A.D.E.R Program rural development fund grant of €7 million ($8 million), which is focused on tourism and Cultural Heritage for both public and private investment in the Belice region, and which could be directed towards restoration or completion of some of the structures in Gibellina Nuova. La Grassa hopes some national or international cultural organizations might use some of the buildings. In others, plans for summer camps for arts and theater are in the works. He is also exploring a formal relationship with Marfa, an obvious “sister city,” and a documentary on their similarities is already in production.

“We need to attract courageous art people, provided they can also maintain a rapport with the farmers,” La Grassa said. But it’s not just the farmers who need attention. Clearly the artists, too, feel as if their donated projects have become “victims” of another kind of neglect. In a new joint venture, the Tenuti Orestiadi has underwritten a study by the Milanese Brera Academy to evaluate and guide restoration of the artworks. (Already Gino Severini’s Natura Morta in Consagra’s Meeting Hall and the replanting of Piero Burzotta’s Orto Botanico have been completed.)

Pietro Consagra, Porta del Cremlino (1996). © Fondazione Manifesto.

While the restoration of old works is ongoing, new works are also being added. In 2017, the duo Sten Lex contributed Varco, a large diptych mural, while artist Christoph Büchel recently reclaimed a garden next to Consagra’s theater and made it into a work of art, titled Concrete Utopia Uncultivated Garden of Coexistence—The Third Landscape, which explores art, plant life, and the culture of gardening.

The municipality has repaired the Chiesa Madre and Santa Caterina church at the base of the Cretto, among other buildings, and the mayor is also working on corporate partnerships. In one exciting new development, the fashion house Yves Saint Laurent has announced its new ad campaign will be set at the Burri Cretto and the Chiesa Madre. Architect Vicenzo Messina, who grew up in Gibellina Nuova and recalls the thrill of being cast in a Robert Wilson production at Orestiadi Festival as a boy, has presented a project for Consagra’s abandoned theater (along with another homegrown architect, Giuseppe Zummo) at the Italian pavilion of the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Marcello De Filippo, Grande Area 85 (1990). © Fondazione Manifesto.

The Center for Social and Economic Research has also opened a Center of Living Memory, which includes a website that aggregates photos, oral histories, and documents from the region. It also supports an initiative to make a new work tax deductible for citizens as part of an ongoing contribution to the “culture” of Gibellina Nuova. Messina says of his parents, “With time, some of them understood what had happened and what they had helped to do.” Cuschera, who visits often, says that he sees “growing curiosity, interest of the young people in their multi-cultural heritage and in the art history of Gibellina.”

Franchini also wants to change the perception of Gibellina as moribund, and allow the citizens of Gibellina “to take back ownership” of their town. He has opened a development office and plans a greenery restoration project. He wants to encourage local purveyors to open shops and is not just concerned with the art tourists who might eventually put the town on the map after their pilgrimages. But, he says, “to finish and polish everything would make no sense. You need to embrace the fact you can’t control everything.”

Italy suffers from massive unemployment and a debilitating refugee crisis. Can the revived “Dream-in-Progress” attract enough attention with so many demands on the national purse and a new right-leaning government gone to the mattresses? Would YSL or Prada be willing to make a more permanent contribution? The divergent proposals remind me of the fractious history of the Vietnam War Memorial and Ground Zero. How much should we depend upon art and architecture to heal wounds?

Alberto Burri, Cretto (1984–2015). Courtesy of Wikipedia.

An influx of state funds finally permitted the completion of Burri’s Cretto in 2011. Climbing the raked “streets” and around windswept corners, startled first by two passing horse and riders and then a small crew preparing a World War I-era film shoot, I found its earlier, graying concrete more evocative of the tragic remains below, even though Franchini says the newer sections more accurately reflect the pristine white that Burri preferred. On the hills above, a recent wind turbine project (rumored to be a Mafia investment) is, alas, the wrong kind of surreal juxtaposition. At the base, the Santa Caterina church, now revitalized in Corrao’s memory, allows the art pilgrims to refresh.

Corrao met a violent end when his young Bengali houseman brutally murdered him with a blow from an ivory statue. (The irony of his demise by an immigrant wielding a piece of art is not lost on me.)

Can you really give a city back its identity? Nicolo Stabile, an advocate who was able to spur funding to complete the Cretto, once described Corrao as a “Fitzcarraldo, [who] knew that those who dream can move mountains.” The passion and energies of La Grassa and Franchini allow me to leave Gibellina Nuova, passing under Consagra’s magnificent entry symbol of promise, Stella (1981), with new hope for this grand experiment.

Mimmo Paladino, Montagna Di Sale (1992). © Fondazione Manifesto.

Tours of Poggioreale, Burri’s Cretto, and Gibellina Nuova are available until November 14 through fondazionemanifesto.org.