Gallery Network

7 Questions for Artist Kendell Geers on His Enduring ‘Fascination With Frontiers’ and a Duchampian Mystery

The artist's exhibition and a new book titled 'Duchamps Endgame' will be unveiled at Wilde Gallery in Basel, Switzerland.

The artist's exhibition and a new book titled 'Duchamps Endgame' will be unveiled at Wilde Gallery in Basel, Switzerland.

Artnet Gallery Network

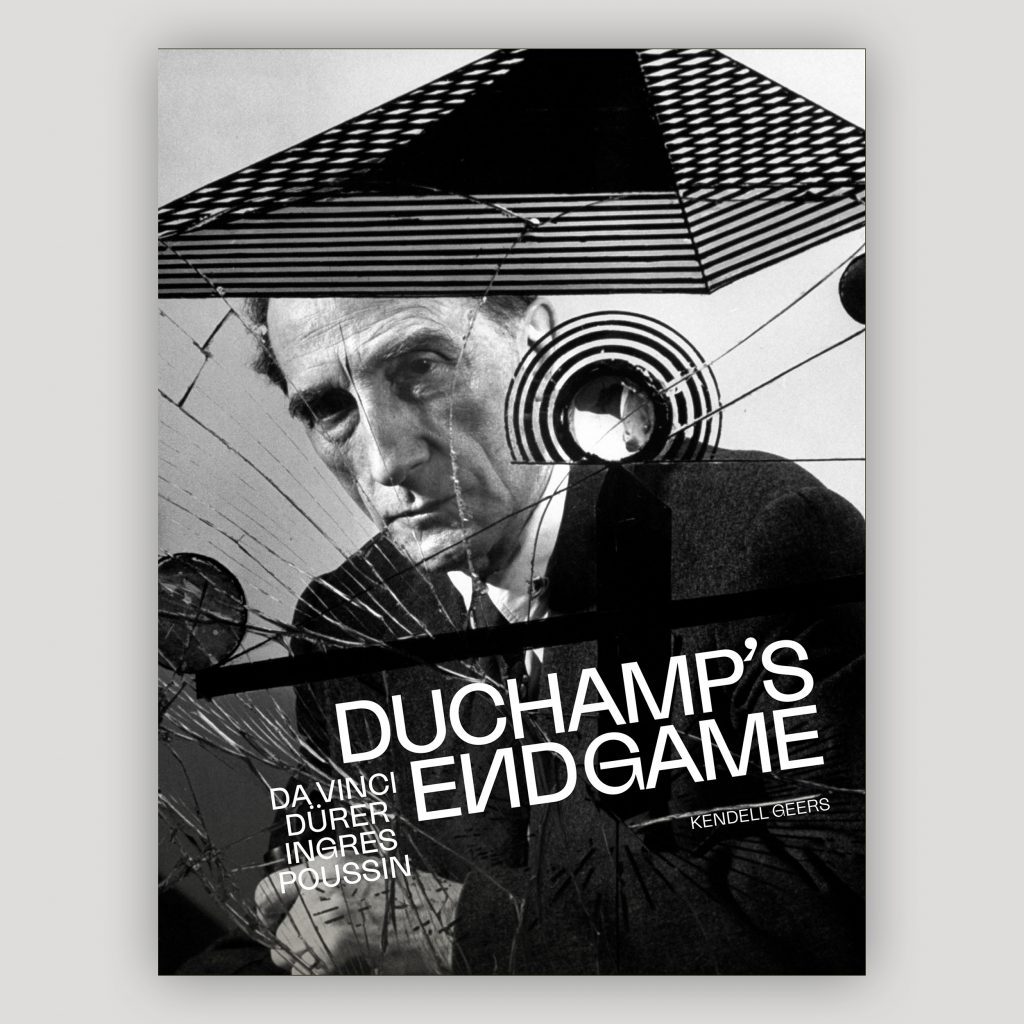

South African conceptual artist Kendell Geers is recognized worldwide for his evocative multidisciplinary practice that frequently subverts social and political norms and reflects deep engagement and research into art history, activism, and culture. Coinciding with Art Basel, Geers’s solo exhibition “The Oculist Witness” opens with Wilde at their Basel location—his first with the gallery and in the city. On view through August 17, 2024, the show features a range of Greers’ works both from the 1990s and more recent, and centers around one of the artist’s newest projects: the publication of his book Duchamp’s Engame, published by Wilde in partnership with Fonds Mercator and Yale University Press.

The week of Art Basel, the book will be available exclusively through Wilde, and an artist talk and book signing will be held at the gallery June 13.

Ahead of the show and book launch, we reached out to Geers to learn more about what visitors and readers can look forward to, and what inspired this significant undertaking.

Installation view of “Kendell Geers: The Oculist Witness” (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Wilde, Geneva, Basel, Zurich.

How does your book Duchamp’s Endgame figure within the show, and how would you like visitors and readers to consider it both on its own and within the context of the exhibition?

In 2023, I closed my studio and stopped making art. I did not have a choice because I needed to distance myself from the art system to take care of my mental health. I had all but given up on returning to the fold when Barth Pralong invited me to make a “statement exhibition” during Art Basel with Wilde Gallery. The timing and challenge were too good to refuse, so I pulled myself out of depression and decided that the exhibition will be a book. Not just any book, but a total recalibration of the 20th-century’s most infamous grandmaster chess playing conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp’s Endgame is the burning core of the exhibition, to which I added a carefully curated selection of works dating back to the 1990s. The book and exhibition are like a game of chess being played through time and across dimensions.

Duchamp’s Endgame: Da Vinci, Dürer, Ingres, Poussin (2024) by Kendell Geers. Published by Wilde in partnership with Fonds Mercator and Yale University Press.

In what ways does the work shown together within “The Oculist Witness” continue or diverge from themes and ideas you’ve engaged with in the past?

In many ways, the project began in June 2001. I made a performative work for Sonsbeek in which curator Jan Hoet was spanked by a local dominatrix. His personality and curatorial methodology were both the subject and object of the work, and reversed the male/female, curator/artist, and European/African power relationships. The work pushed institutional critique to the limits, and I felt that the next step would have been problematic, so I took a year away from making art and focused on researching the history of art and the influence of politics and faith. It felt as if the path that post-war art had taken was a dead end and grew ever more curious about the origins of the avant-garde language and roots of abstraction. Art is an open-source language that each generation of artists copies, pastes, edits, adds to, and subtracts from.

How would you describe your process, where do you start? Do you work on one piece at a time, or envision collections or bodies of work holistically?

I am a white African artist and that places me in a rather unique, albeit extremely uncomfortable, position. Even though my family has been living in Africa for three centuries, I am still not considered African by many people simply because I am white. On the other hand, my cultural background and identity are quintessentially African, so I don’t belong in Europe either and I find myself trapped on the border and the in-between. Consequently, I am fascinated by frontiers because whilst they protect us, they also imprison us. It used to bother me that I don’t belong anywhere, but I have since found strength by embracing my contradictions as a methodology and developed a meta practice that is defined by the fluidity of my identity. I might even define my work as pan-aesthetic surgery.

Kendell Geers, Rack (2009). Courtesy of the artist and Wilde, Geneva, Basel, Zurich.

Marcel Duchamp is a core element of the show, what initially drew you to his work? Are there any other historical artists you find similar resonance with?

The full title of the book is Duchamp’s Endgame: da Vinci, Dürer, Ingres & Poussin, and that list could have also included Lucas Cranach the Elder, Guercino, Hans Baldung, Raphael, Man Ray, and of course Francis Picabia.

Growing up during Apartheid South Africa, it was compulsory for every white man to go to the military and the only way to avoid conscription was to continue studying. I ran away from home at 15 and was absolutely against the Apartheid regime so refused to go to the army. The only way to avoid being sentenced to six years in civilian jail as a war resister was to endlessly study. As I weighed my options and tried to decide what I might study, I encountered the work of Duchamp and Picabia. I was taken by their cross-dressing, anti-authoritarian, iconoclastic attitudes, so I decided that going to art school to stay out of jail would be my destiny. I became an increasingly militant Anti-Apartheid activist and eventually had to flee the country as a refugee. In 1989, I ended up in New York where I worked as an assistant to Richard Prince, and finally returned to South Africa after Mandela was released.

Installation view of “Kendell Geers: The Oculist Witness” (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Wilde, Geneva, Basel, Zurich.

What is one thing you would like most for visitors of the show to take away with them?

The book is about how artists look at the work of other artists very differently than art historians or curators. It examines their work as prisms that separate perception from what we think we see or from what we assume to see, both of which have been influenced by what we have been told to see, none of which has anything to do with what we are looking at.

Ultimately, the book answers the question about what happened in 1912 when Duchamp fled to Munich for three months and made two oil paintings and three drawings, which became the basis for everything that followed. For more than a century, art historians have tried to decode these works, but they have been looking in the wrong place. These works are the key, but they are also the lock, because they contain everything we need to know if we look beyond the obvious.

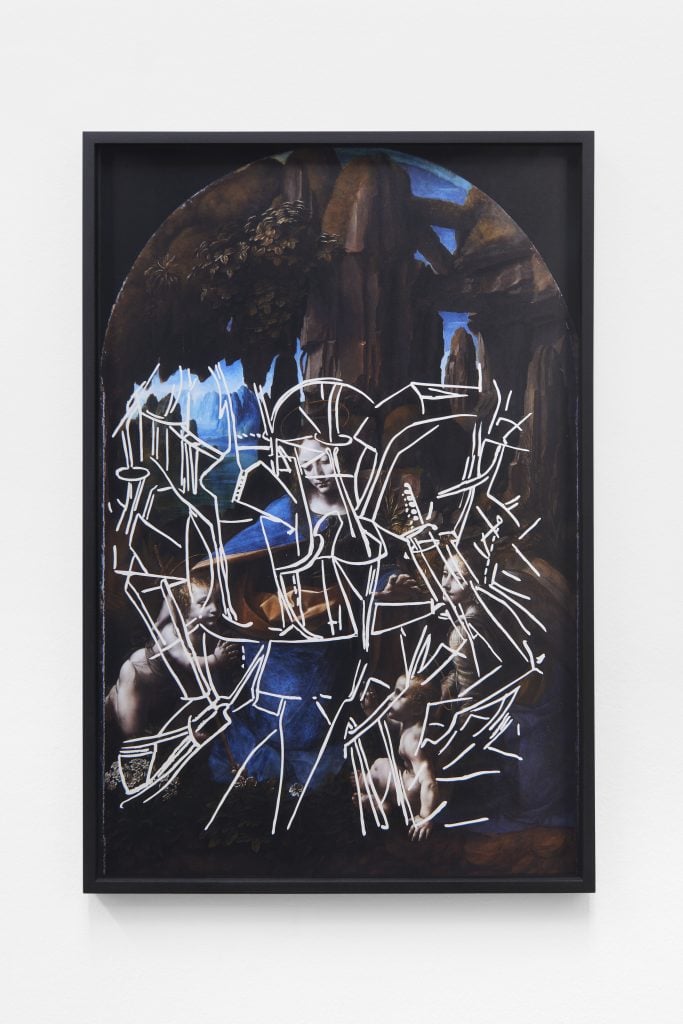

Each of them has been abstracted from an old master painting by either Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, or Dürer. Two, for example, are traced from da Vinci’s two Virgin of the Rocks (1491/2-9 and 1506-8) paintings. Of the five works, only Dürer’s Virgin as Mother of Sorrows (1495–98) was actually in Munich, and almost certainly traced it from a book. The connection to Munich was through a process of abstraction outlined by Kandinsky in his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which was published in 1912.

If there is one thing that I would like viewers to take away with them it is that great art cannot be simplified into an easy, comforting explanation, and even if it takes a century to perceive, great art will always shift our perceptions by shaking the tree of our assumptions.

You make it sound so obvious so why did it take so long to see?

I ask myself that exact same question and spent many sleepless nights wondering if I have seen something that is not there. Every morning, I traced the lines again and always they lined up. Interestingly, Duchamp’s Endgame grew out of a lecture I gave 10 years ago called “Following the Blind Man” in New Delhi, as part of an exhibition curated by RAQS Media Collective. I gave different versions of the same lecture in Chicago, Philadelphia, Toronto, Brussels, and New York. Perhaps I needed the weight of a printed book to be heard?

Having said that, I think the most troubling aspect of the book will be realizing that Duchamp’s final painting Tu m’ (1918) was really based on art history’s even more enigmatic painting, Et in Arcadia Ego (1637–38) by Nicolas Poussin. Both paintings have complex titles that are missing a verb, and both are compositionally centered upon a tomb and hand with outstretched index finger pointing towards mysterious shadows. Ever since it was painted in 1638, Et in Arcadia Ego has puzzled art historians, but the answer was hidden in plain sight. The Poussin painting, Duchamp’s Passage from Virgin to Bride (1912), and Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864) are all based on da Vinci’s Virgin of the Rocks. The Ingres, Poussin, and da Vinci all hang a few hundred meters apart, all in the same museum, so yes, the question really is why did it take so long to see the links between them?

Kendell Geers, Oculist Witness, Le Passage de La Vierge à La Mariée / Virgin of the Rocks (2014). Courtesy of the artist and Wilde, Geneva, Basel, Zurich.

What are you working on now, or planning to work on next?

Being an artist is a calling more than a career, so I don’t plan ahead. I simply follow my work and try to understand where the research wants to take me. Duchamp never actually said that painting was dead so much as that he was tired of the stupidity of painters. He really wanted to restore art to the service of the mind, and I hope that my book will rekindle an interest in art that is more than about visual stimulation. Secretly, I hope perhaps that after realizing how much we have missed in the work of Duchamp, da Vinci, Dürer, Ingres and Poussin, the sensitive reader might reconsider what they have assumed about my work.

“Kendell Geers: The Oculist Witness” is on view at Wilde, Basel, June 10–August 17, 2024.