Up Next

‘It’s All About Secrets’: Inside Mexican Artist Paloma Contreras Lomas’s Baroque Worlds

The rising artist's works have recently been showcased at Independent Art Fair and CARA in New York.

The rising artist's works have recently been showcased at Independent Art Fair and CARA in New York.

Katie White

“I have an obsession with Mexicanity,” said artist Paloma Contreras Lomas on a phone call from her CDMX studio earlier this spring. “It’s an obsession with the way history and contemporary violence have been built around pop culture and projected onto Mexico.”

Contreras Lomas (b. 1991) thrives in a complexity of meanings, creating multifaceted works she often describes as “Baroque.” A former member of the acclaimed Biquini Wax EPS artist-run space, Contreras Lomas is regarded by many as one of the most significant voices in Mexican contemporary art. Over the past decade, she has cultivated a wide-ranging practice encompassing film, writing, drawing, performance, sculpture, and painting. Recently, she’s garnered increasing attention from the U.S. art world.

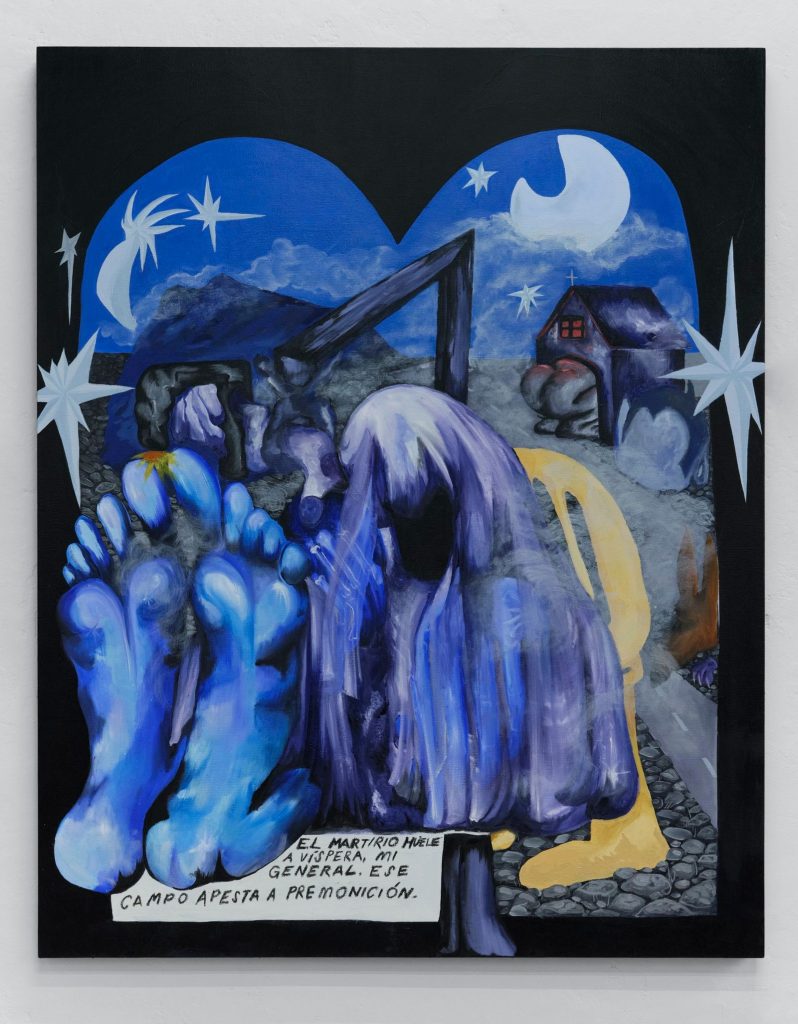

Paloma Contreras, Lomas El martirio huele a víspera (2024). Courtesy of Pequod Co.

In May of this year, Galería Agustina Ferreyra and Pequod Co. jointly presented recent paintings by the rising star at the Independent Art Fair in New York. Contreras Lomas’s paintings feel at once folkloric and comic, pairing monstrous entities with reinterpretations of pop culture figures, like Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny, and Bart Simpson. Like most of Contreras Lomas’s practice, the paintings buck categorization.

“The Baroqueness of my work is very Mexican,” she said “Mexico is a country with a subtext. In my work, I do not say everything that I want to say.”

At the 2023 iteration of Desert X, hosted in Palm Springs, the artist presented Amar a Dios en Tierra de Indios, Es Oficio Maternal (2023), a large-scale installation of a vintage car spilling over with plush, fuzzy soft sculptures ranging from cartoonish cacti to a tangle of limbs. The work embodies many of the tensions in the artist’s work; the work is opulent and alluring, the sculptures touchable and colorful, but a closer look reveals alarmingly violent themes. “I was thinking of this American obsession with cars and cinema—movies of serial killers going up to people kissing in their cars,” the artist said.

Paloma Contreras, Amar a Dios en Tierra de Indios, Es Oficio Maternal (2023). Courtesy of Pequod Co.

Installed at the historic estate of Sunnylands, the former summer home of Ambassadors Walter and Leonore Annenberg and a famed diplomatic destination, the installation did feel cinematic, conjuring up a pastiche of horror and Western aesthetics while ruminating on violence against women, trafficking, and border crime.

“Sunnylands is this oasis in the desert and this artificial ecosystem,” she explained. “These are the places that politicians and rich people go—where everyone is so nice and everything is blooming—even though it’s the desert. It’s suspicious and a metaphor for how politics work in the Americas.”

This spring, Contreras Lomas presented a reinterpretation of Amar a Dios en Tierra de Indios, Es Oficio Maternal in a two-artist show with Austrian artist Ines Doujak at the Center for Art, Research and Alliances (CARA) in New York. The exhibition presented an intergenerational look at feminist artistic discourse and a shared fascination with subcultures and the grotesque. “Ines has a body of work that’s so extensive and it’s important for me to honor the work of artists who have been working long before me,” said Contreras Lomas. “We both have a very similar sense of humor, even though our productions can be very different.”

Installation view “Paloma Contreras Lomas and Ines Doujak” 2024. Courtesy of Center for Art, Research, and Alliances.

Humor—a discomfiting, anxious wit—is central to Contreras Lomas’s practice. The artist, who grew up in a middle-class family, remembers her father’s books of political cartoons intriguing her. She was captivated by the way satire and jest could often get to the heart of complex and serious subjects.

“Humor is not a way of softening these topics. I’m not being cynical, but it’s a way of being generous as a way of approaching topics like this,” she said, “To me, there is something both humorous and perverse in creating soft sculptures that are attractive and touchable but also disturbing.”

The artist doesn’t exempt herself from this critiquing humor. Most of her works—films, sculptures, or drawings—are generated from autobiographical writing exercises, if even obliquely.

Installation view “Paloma Contreras Lomas and Ines Doujak” 2024. Courtesy of Center for Art, Research, and Alliances.

“When I went to art school, I had a naiveness. I thought I could actually help people. But I’m a middle-class artist, not an anthropologist,” she said “Essentially, I’m a tourist to these experiences of violence. I call my work a genre of ‘middle-class horror.’ It’s the stupidity of the intellectual class going into certain topics or places. But I’m that person—even if it’s in bad taste.”

Her fiction writings draw from these dark fascinations—bridging true crime and horror with science fiction—telling of a world of ghosts and inspectors. These visions sometimes translate from the page into her visual practice. Contreras Lomas acknowledges that her works are more enmeshed with pop culture than anything else.“I’m much more influenced by cinema and fashion and television than contemporary art itself,” she said.

Horror films and true crime podcasts particularly captivate her. “ Mexico is the country that most consumes true crime,” she said. “In a country where we don’t get answers from the state about people who have disappeared, Netflix becomes a private investigator for the people. I’m obsessed with this kind of storytelling.”

Installation view “Paloma Contreras Lomas and Ines Doujak” 2024. Courtesy of Center for Art, Research, and Alliances.

For the artist, introducing her work to new audiences—American audiences—has offered her new insights into her own artistic outlook.

“The American public asks about everything, every symbol. What does a cactus mean? There is an obsession with representation and what it means—this is part of being from a country of transparency where people are used to being given answers,” she explained. For Contreras Lomas, power comes from a place of resistance to clear responses, obfuscation, and layering.

“Mexicanity that has to do with another kind of truth. If you ask me something, I might tell you one thing, but in reality, it’s another. That’s a Latin American way of thinking, it started as a resistance to transparency with colonizers,” she explained “Mexico is a country filled with sad, obscure, and urgent symbols. It is a graveyard with layers. When I draw, I hide things. When I draw, it’s all about secrets.”