Archaeologists are improving our understanding of the ancient world at a pace that feels more rapid than ever. Technological advances are accelerating our discovery of prehistoric civilizations, extinct species, and other mysteries of bygone eras.

Last year alone saw the discovery of the world’s oldest known shipwreck, dating to the time of ancient Greece, and what may be the world’s oldest known figurative art, the 40,000-year-old cave paintings identified via a new method of flowstone dating.

And just this past week, archaeologists announced that the Lovers of Modena, two skeletons romantically preserved arm-in-arm, are actually both men. We’re even learning new things about good old King Tut, like the fact that the boy king’s dagger was likely made from a meteorite.

And although we may not have yet topped historic discoveries like Tut’s tomb, famously uncovered by Howard Carter in 1922, or Heinrich Schliemann’s excavation of the mythical city of Troy in 1870, there have still been many mind-blowing archaeological finds in the past decade. Here are our top eight.

The Lost City of Tenea

An aerial shot of the ruins of the lost city of Tenea. Photo courtesy of the Greek Culture Ministry.

Last fall, Eleni Korka, one of Greece’s leading archaeologists, finally discovered the site of Tenea, a city founded by the Trojans following the Trojan War and built by prisoners of war. The discovery, in the Peloponnese region of southern Greece, marked the end of Korka’s decades-long search in the area, begun back in 1984.

Over the past year, about 200 coins have been found on the site, an extraordinary number that demonstrates the wealth of Tenea, which was mentioned in ancient texts including the legend of Oedipus. Korka’s team of archaeologists believes the city, once home to 10,000 people, was raided by the Visigoths and, some 200 years later, by the Slavs before being abruptly abandoned. As excavations continue, they expect to find additional homes, temples, and the city marketplace, or agora.

“It’s like an iceberg and we’re just hitting the tip,” Korka’s colleague Konstantinos Lagos told the BBC. “It’s going to keep giving interesting findings for the next 100 years.”

Spanish Stonehenge

Photo of the Dolmen of Guadalperal. Courtesy of Ruben Ortega Martin, Raices de Peraleda.

Long submerged beneath the waters of the Valdecañas Reservoir, the Dolmen de Guadalperal, better known as the Spanish Stonehenge, was made newly visible this summer as drought struck Spain’s Extremadura region.

The Dolem de Guadalperal consists of about 100 monolithic stones, some reaching as tall as as six feet, and is 7,000 years old. The site has been underwater since the government built the reservoir in 1963.

“Like Stonehenge, [the megaliths] formed a sun temple and burial ground,” local resident Angel Castaño told the Local. “They seemed to have a religious but also economic purpose, being at one of the few points of the river where it was possible to cross, so it was a sort of trading hub.”

1,000 New Ancient Maya Sites

A LiDAR scan of Caracol, a Maya city in Belize. Image courtesy of University of Central Florida Caracol Archaeological Project.

One of the most shocking revelations of the decade came in 2018 when archaeologists in Guatemala announced that thousands of unknown Maya structures hidden in the jungle had been revealed thanks to a new technology—planes from the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping equipped with high-tech Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) mapping tools. In an instant, the LiDAR takes topographical readings, creating three-dimensional maps of the earth’s surface that would take years to plot on foot.

Maya archaeologists have always had difficulty navigating the dense tropical undergrowth, which obscures the ancient ruins and makes it impossible to see most Maya structures beyond a few feet away when on the ground. That’s especially true when it comes to the networks of low roadways, causeways, and irrigation systems that were discovered en masse thanks to the LiDAR.

“LiDAR is showing us things that we never would have been able to see with 100 years of research—and we have 100 years of research under our belts already, so it’s not like that’s hyperbole,” archaeologist Marcello Canuto, who helped oversee the LiDAR initiative from Pacunam, told artnet News.

The Hidden Palace of Ramesses II

Special hieroglyphic symbols denote the name of Ramesses II at a previously undiscovered palace at the ancient site of Abydos. Photo courtesy of Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities.

In March, an excavation team from New York University announced that a previously unknown palace has been discovered next to the Temple of Ramesses II in the ancient Egyptian city of Abydos. Archaeologists thought they had found the full temple 160 years ago, until the stone walkway leading to the adjoining building, a secret royal palace marked with the cartouche of Ramesses II, was uncovered.

Previously, the prevailing theory was that Abydos, home to a temple and burial ground, was mainly used for ceremonial purposes. “The fact Ramses II required a palace at Abydos also reveals that he didn’t just order a new temple at the site but was spending enough time there to warrant such accommodation,” NYU professor Joann Fletcher told Newsweek. “To have a building in which people lived their lives is always a fascinating thing to find.”

Buried Treasure in an Ancient Greek Tomb

Excavation leaders Sharon Stocker and Jack Davis have worked in the Pylos region of Greece for 25 years. Photo courtesy of the University of Cincinnati.

A husband-and-wife team from the University of Cincinnati was digging near the ancient Palace of Nestor, in the town of Pylos on the southwest coast of Greece, when they literally unearthed buried treasure: a cache of bronze weapons, gold and silver cups, and hundreds of precious and semiprecious beads of amethyst, carnelian, amber, and gold.

“It was surreal,” one of the archaeologists on the dig, Flint Dibble, told Smithsonian Magazine. “I felt like I was in the 19th century.”

Aside from its incredible wealth, the remarkable tomb offers new insights into the roots of European culture, and about links between the ancient Mycenaean society on mainland Greece and the Minoans on the island of Crete. The two cultures were likely intertwined, together giving birth to what we think of as Western civilization.

The Oldest Human Jawbone Outside of Africa

This fossilized human jawbone was discovered in Israel, suggesting that Homo sapiens first migrated out of Africa at least 50,000 years earlier than previously thought. Photo by Gerhard Weber, courtesy of the University of Vienna.

A human jawbone unearthed by a team from Tel Aviv University in Misliya Cave on Israel’s Mount Carmel in Israel offers new evidence that humans migrated beyond Africa some 50,000 years earlier—or more—than previous research had led experts to believe.

The fossil was discovered in 2002 by a freshman on his first archaeological dig, but news of its significance was only announced in 2018. The archaeologists dated burnt flint flakes that were also found in the cave to 250,000 to 160,000 years old, far earlier than the other evidence of modern humans outside of Africa, which places their earliest migration at 120,000 years ago.

The jawbone “looked so modern that it took us five years to convince people, because they couldn’t believe their eyes,” said Mina Weinstein-Evron, an archaeologist on the project from the University of Haifa, told the New York Times.

Germany’s 10 Million-Year-Old Teeth

Researchers say that this tooth—recently discovered at a fossil site in Germany—is the upper left canine of an ancient Eurasian primate. (From this angle, the canine’s tip is jutting outward.) Photo courtesy of Herbert Lutz.

This one is controversial. In 2016, archaeologists in Eppelsheim, Germany, discovered two 9.7 million-year-old teeth. They weren’t exactly human, but they bore a close resemblance to the teeth of Lucy, the famous fossil of Australopithecus afarensis, an early ancestor of homo sapiens. These teeth were four million years older than Lucy, the oldest species of hominins, the subfamily including human, extinct humans, and their immediate ancestors.

But National Geographic was quick to warn against sensationalizing the find by describing it as evidence that mankind originated in Europe, rather than Africa. (Newsweek proclaimed the fossils “could rewrite human history.”) The teeth may belong to an extinct hominoid primate only distantly related to humans—or to an entirely different type of species, possibly even a ruminant animal. More research is definitely needed for this fascinating discovery.

“We want to hold back on speculation. What these finds definitely show us is that the holes in our knowledge and in the fossil record are much bigger than previously thought,” said study leader Herbert Lutz, the deputy museum director of Germany’s Mainz Natural History Museum, to ResearchGate. “It’s a complete mystery where this individual came from, and why nobody’s ever found a tooth like this somewhere before.”

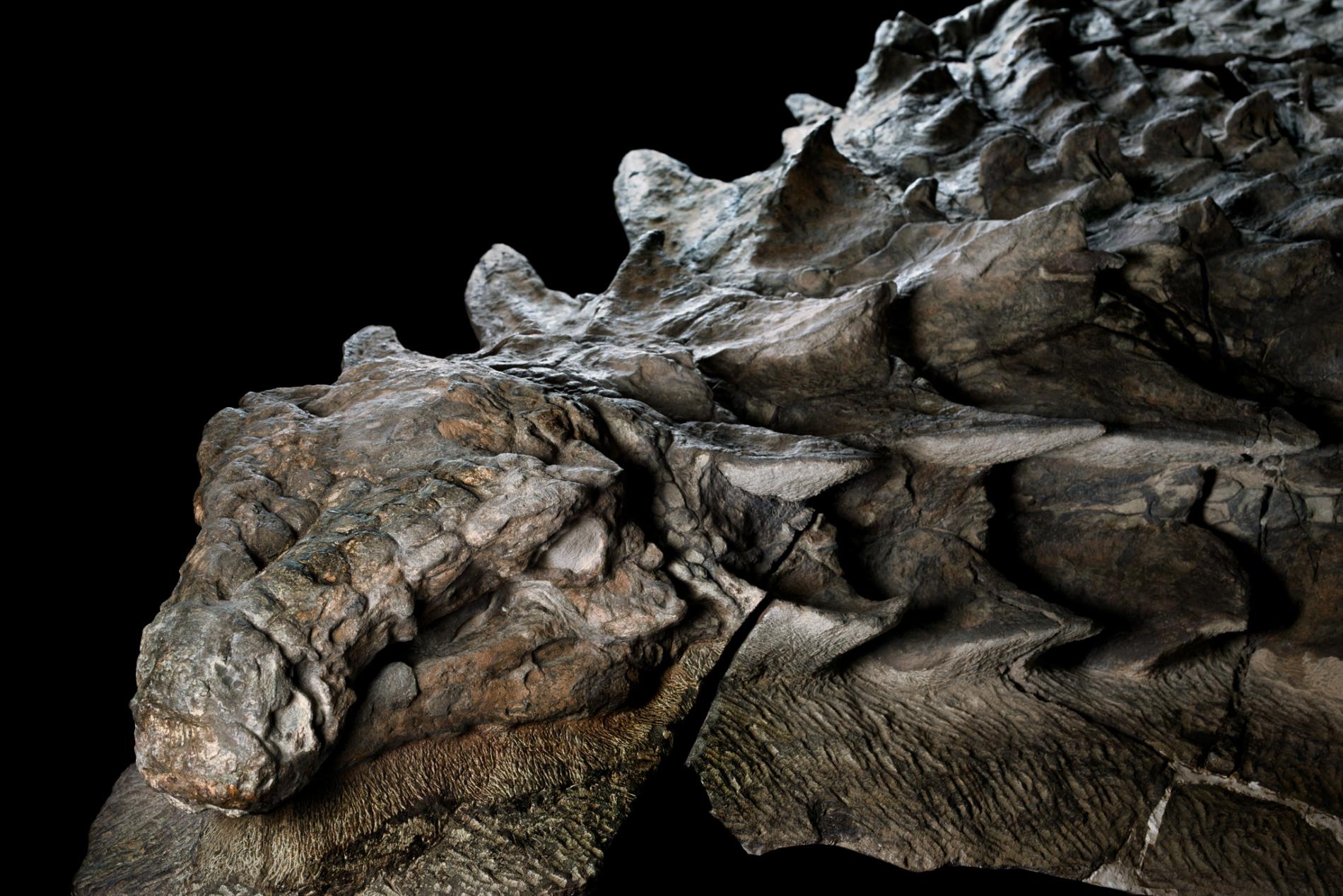

Mummified Dinosaur

While digging at a Canadian mine one day in 2011, a worker was shocked to discover an almost perfectly preserved 110 million-year-old nodosaur specimen. Paleontologists are used to uncovering the fossilized bones and teeth of ancient dinosaurs, but it is much less common for the skin and other soft tissue to survive for millions of years. Here, the bones aren’t even visible, because the flesh, heavy body armor, and scaly skin remains intact.

After 7,000 hours of painstaking work by a fossil preparator, the incredible find, weighing 2,500 pounds and measuring 18 feet long, was unveiled at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Alberta, Canada, in 2017. Unexpectedly, analysis of the skin showed shading that indicates that the plant-eating nodosaur, despite its size, used camouflage to conceal itself from predators.

“It will go down in science history as one of the most beautiful and best-preserved dinosaur specimens,” said the museum’s Caleb Brown in a statement, calling the nodosaur “the Mona Lisa of dinosaurs.”