Art World

This Year, Archaeologists Discovered How the Egyptians Built the Pyramids. Here Are 16 Other Amazing Discoveries of 2018

From tombs in ancient Egypt to the "holy grail" of sunken treasures, it was a big year for cultural discoveries.

From tombs in ancient Egypt to the "holy grail" of sunken treasures, it was a big year for cultural discoveries.

Sarah Cascone

Among the biggest headlines of the year were for stories about unbelievable, sometimes history-making cultural discoveries. There was the identification of a long-lost Andrea Mantegna painting, previously mistaken for a lowly copy, and the archaeologists who found the mythical city of Tenea, built by the Trojans and lost for generations.

Here’s our roundup of the best—and worst—creative discoveries of the year.

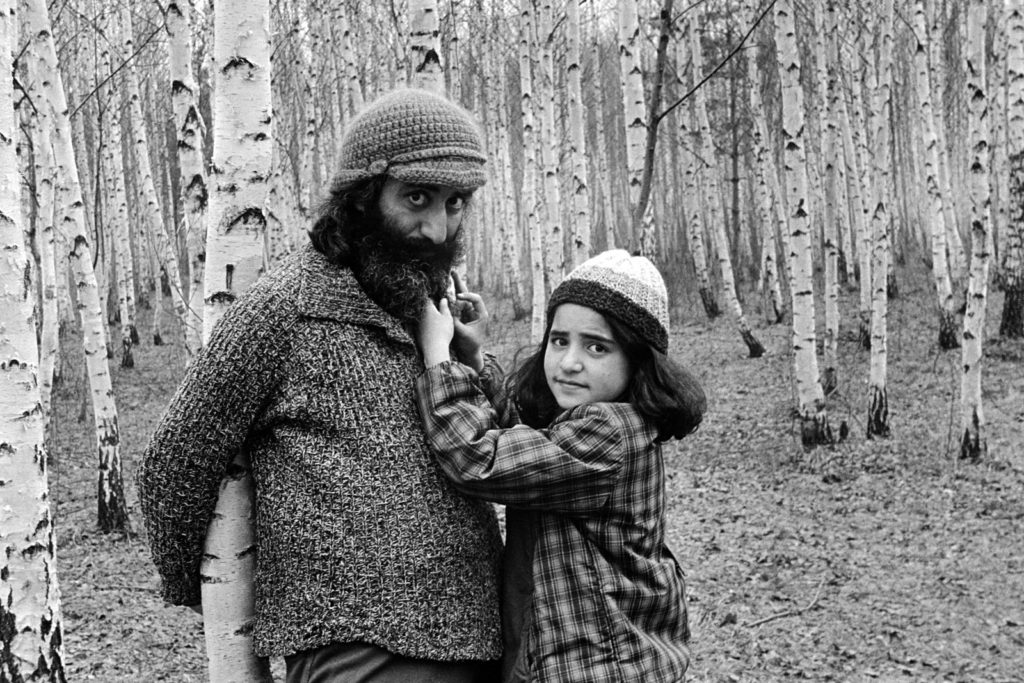

Masha Ivashintsova’s photo of her husband, Melvar Melkumyan, and her daughter Asya Ivashintsova- Melkumyan. Leningrad, USSR (1980).

For decades, Masha Ivashintsova took photographs of life under the Soviet regime, hiding the undeveloped film and negatives away in her St. Petersburg attic. She died in 1990, but it wasn’t until last year that her family discovered her life’s work and began developing some of the 30,000 unseen images. The first batch of photographs was unveiled this year, a series of black-and-white images depicting the artist’s family, as well as slice-of-life street photography.

Ivashintsova’s unsung creative genius has invited comparisons to the American nanny Vivian Maier, whose prolific work as a photographer was only discovered posthumously in 2009. Expect to be hearing more from Ivashintsova as her family considers opportunities to sell and exhibit her work.

The world’s oldest figurative art was found in this Borneo cave. Photo by Pindi Setiawan.

Ancient cave art kept making headlines this year. There was the discovery of both the world’s oldest depiction of a supernova and a paper that made the case that prehistoric cave paintings were actually sophisticated astronomical dating systems based on the movements of the heavens, with the animals standing in for constellations.

Meanwhile, in a Borneo cave, archaeologists used a new method of flowstone dating to identify what they claim is the world’s oldest figurative art, from 40,000 years ago.

Topping them all, should the marks truly have been made intentionally by human hands, are a set of nine red strokes dated to some 73,000 years ago, found in a South African cave. Some experts doubt that the red ocher pigment are actually abstract drawings, but if they are, they predate all other known examples of Homo Sapiens’ art by 30,000 years—and are even older than the 65,000-year-old Neanderthal cave art identified in a series of Spanish caves in February.

The Roman horse’s head pre-restoration. Photo: J. Bahlo, German Archaeological Institute.

A German farmer got a happy ending after suing his local government for shortchanging him following the discovery of a remarkable 2,000-year-old bronze horse head on his property in 2009. Incredibly well preserved, the ancient Roman sculpture was unearthed at the bottom of a 36-foot-deep well, likely hidden as townsfolk fled from an invading force.

The government initially awarded the farmer just €48,000 (about $56,000), but once he saw news articles celebrating the find, he began to suspect he’d received a raw deal. (Archaeologists now believe the horse head was part of a larger work that would have featured a rider, the illustrious Caesar Augustus.) The courts agreed, ruling in July that the farmer should have received half the work’s estimated value of €1.6 million ($1.8 million), meaning that the government owed him €773,000 (nearly $904,000)—plus interest.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Studies of hands for the Adoration of the Magi Sheet 2 (c.1481), under ultraviolet light. Courtesy of Royal Collection Trust/Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

As the world prepares to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci in 2019, experts have been taking a closer look at the life’s work of the Renaissance great. While examining works on paper ahead of the touring UK show “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing” researchers using high-energy X-ray fluorescence found elegantly drawn images on seemingly blank pages.

Leonardo didn’t intend to use invisible ink, however. The images are instead a trick of the passage of time, a chemical reaction turning the ink into a transparent copper salt. The exhibition will reveal these lost drawings, as well as showcase changes made by the artist during the drawing process, which can be seen thanks to infrared light.

An Imperial Yangcai crane and deer Ruyi vase. (18th century). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

An 18th-century Imperial “Yangcai” Famille rose vase found in a French attic was brought to Sotheby’s in a shoebox for appraisal—and proved valuable beyond the owner’s wildest expectations. Because most known pieces of Yangcai are in the collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei the vase was extremely rare and went on to sell for €16.18 million ($19 million) at Sotheby’s, a stunning 32 times the pre-sale estimate.

Another collector who stumbled across unexpected finds this year brought an early America teapot, originally purchased for £15 ($20) at an antiques fair, to sell at auction to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a staggering £460,000 ($520,000).

Bronze Age artifacts discovered by a local dog named Monty. Image courtesy of Hradec Králové Region.

It doesn’t get much better than the story of Monty, a dog in the Czech Republic that went for a walk and uncovered a cache of buried Bronze Age artifacts some 3,000 years old. The rare find included 13 sickles, two spear points, three axes, and numerous bracelets.

Monty’s keen nose has led to numerous searches with local experts, but so far the professional archaeologists have been unable to match his incredible find. (For his trouble, Monty’s owner received a 7,860 CZK ($360) reward.)

Other noteworthy, equally unlikely finds include a jar full of golden Roman coins found in the basement of a theater in Como, Italy, and a 3,400-year-old tomb uncovered in an olive grove in Crete after the earth beneath the farmer’s car gave way.

Willem de Kooning, Untitled II (ca. 1970). Photo courtesy of David Killen Gallery.

Art dealer David Killen stumbled upon a goldmine when he bought the contents of an unclaimed storage unit in New Jersey for $15,000. It had belonged to a conservator who once worked for New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and alongside the mostly minor artworks inside were a half-dozen abstract paintings on paper that were labeled “Willem de Kooning.”

Although the artist’s foundation does not authenticate works, the six paintings went on to sell for a combined $2.5 million earlier this month. Similar works with the artist’s signature have gone for as much as $4.2 million each, so don’t be surprised if the paintings resurface again in a few years.

A carved black wooden sarcophagus inlaid with gilded sheets discovered by an Egyptian archaeological mission on the west bank of the Nile north of the southern Egyptian city of Luxor. Photo by Khaled Desouki/AFP/Getty Images.

It was a banner year for Egyptian archaeology, with discoveries that included an ancient sphinx found by construction workers in August and a perfectly preserved royal priest’s tomb, hailed as one of the most significant finds in the past decade. The country is hoping that the recent spate of high-profile discoveries will help boost flagging tourism in the region, which has declined in recent years due to political instability.

Other finds include two important tombs, announced in November, and government officials even opened a mummy from one of the sites in front of the press. Archaeologists also announced that they think they now have a definitive understanding of how they Egyptians built the pyramids thanks to the discovery of a quarry featuring a complex system of ramps and post holes.

Iron Age square barrows, Pocklington, Yorkshire. Photo: Emma Trevarthen. Copyright Historic England.

One positive effect of global warming? Unprecedented temperatures in the UK have actually led to archaeological discoveries such as crop marks, which indicate the presence of ancient buried structures and are more easily detected in bone-dry soil.

This year’s bumper crop of discoveries included Stone Age monuments, Iron Age settlements, a Roman farm, and the foundations of an Elizabethan hall—but as cool as it is to uncover the remnants of lost buildings, the overall implications of this year’s record heat, and the potential negative effects of climate change, land these finds on our “worst” list.

Teacups at the site of the San Jose shipwreck. Photo courtesy of REMUS image and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

In May, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution confirmed that the legendary treasure of the San José, a Spanish ship that sunk off the coast of Colombia in 1708, had been found intact among the wreckage. The long-lost cargo, considered the “Holy Grail” of shipwrecks, could be worth as much as $17 billion.

What’s the bad news, you ask? There’s already a fight over who gets to recover the golden trove. A US company claims that it first identified the wreck’s coordinates in 1981 and is therefore entitled to split the treasure with Colombia, as per a 2011 ruling. Meanwhile, Spain wants its treasure back. Sadly, this exciting find seems destined to end in a long, drawn-out court battle unworthy of tales of swashbuckling on the high seas.

The contents of a recently discovered sarcophagus that some hoped held the remains of Alexander the Great. Photo courtesy of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities.

It was impossible not to get excited over the possibility that a large granite sarcophagus discovered in Alexandria in July might have held the remains of the port city’s namesake, Alexander the Great. Despite the warnings of Egyptian officials, who insisted there was nothing to the rumors, the date wasn’t too far off from the famed conqueror’s time, and the dark, mysterious coffin had a commanding aura to it that suggested the find was truly significant.

Although the contents were interesting—one of the three skeletons inside had a hole drilled into its head, evidence of trepanning, an ancient form of brain surgery—the definite lack of Alexander was a big let down. And the signatories of a Change.org petition who demanded they be allowed to drink the red liquid in the sarcophagus, assumed to be sewage, in order to “assume its powers and finally die,” were similarly disappointed.

On the plus side, fearful rumors that opening the mummy could unleash a deadly curse has also thus far proved unfounded.

Details from the five Vincent van Gogh sunflower paintings included in the Facebook Live virtual exhibition. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Vincent van Gogh’s famed sunflower paintings are without a doubt among his most beloved masterpieces, but it’s not clear how much longer the world will be able to enjoy them—at least in the way that we see them today. A team of scientists from the University of Antwerp and the Delft University of Technology have found that Van Gogh’s chrome yellow pigments are starting to turn brown.

The paint’s potential oxidization has been noted before, in a 2015 study. The following year the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam set out to restore one of the sunflower paintings. Luckily, the change isn’t yet perceptible to the naked eye, and we can help slow the process down by limiting the works’ exposure to light.

This skeleton of a man killed by a falling rock while fleeing the eruption of Vesuvius was recently discovered at the archaeological site of Pompeii. Photo courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Pompei.

Archaeologists at Pompeii found a particularly gruesome skeleton in May, when they unearthed the remains of a man who had managed to make it out of Pompeii, only to die when a block of stone sent flying by the erupting Vesuvius hit him head on and apparently decapitated him.

As it turned out, the head’s placement had shifted during earlier excavations and was found, intact, lower down in the dig. But while a flying projectile didn’t crush his cranium, the man’s death was still pretty horrific: National Geographic reports that he was engulfed in a deadly pyroclastic flow, a cloud of toxic gas as hot as 1000 degrees being ejected from the volcano with the strength of hurricane-force winds.

The Voynich manuscript has baffled scholars for centuries. Photo by Cesar Manso/AFP/Getty Images.

It would have been truly exciting if we finally knew what the fabled, gorgeously illustrated Voynich manuscript, which has held its secrets for 600 years, was actually about.

But the method used to decode the mysterious text—which researchers recently claimed was originally written in Hebrew—doesn’t apparently hold up to scrutiny. The artificial intelligence-driven algorithm analyzed the manuscript based on modern languages, but the grammar, spelling, and vocabulary from a 15th-century manuscript would have been dramatically different than the way it is used today.

No wonder the team had to make spelling corrections before Google translate was able to make heads or tales of the “Hebrew” original!

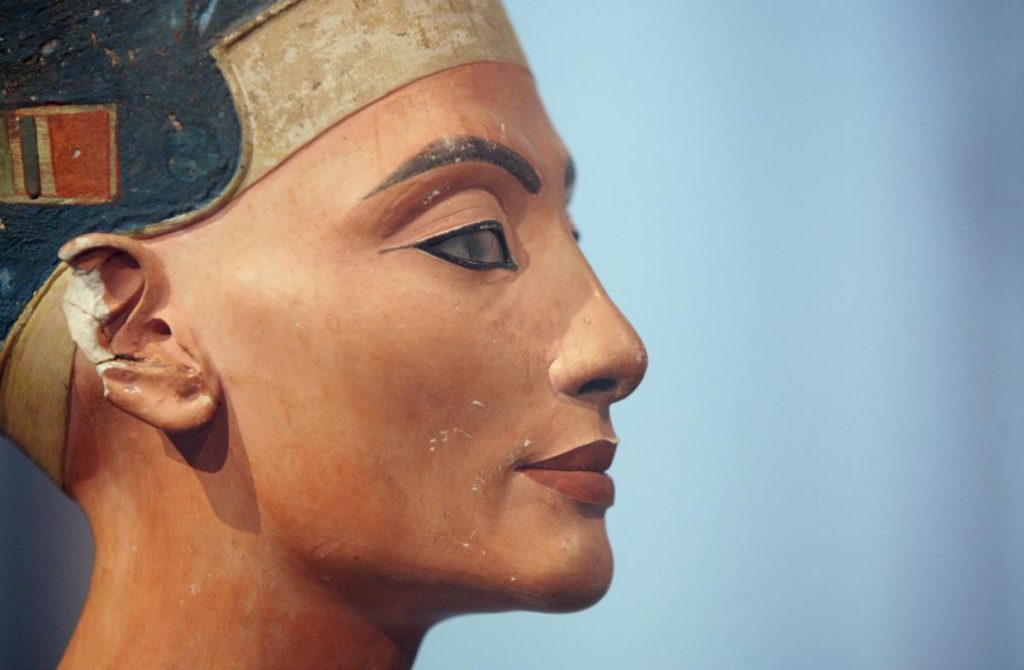

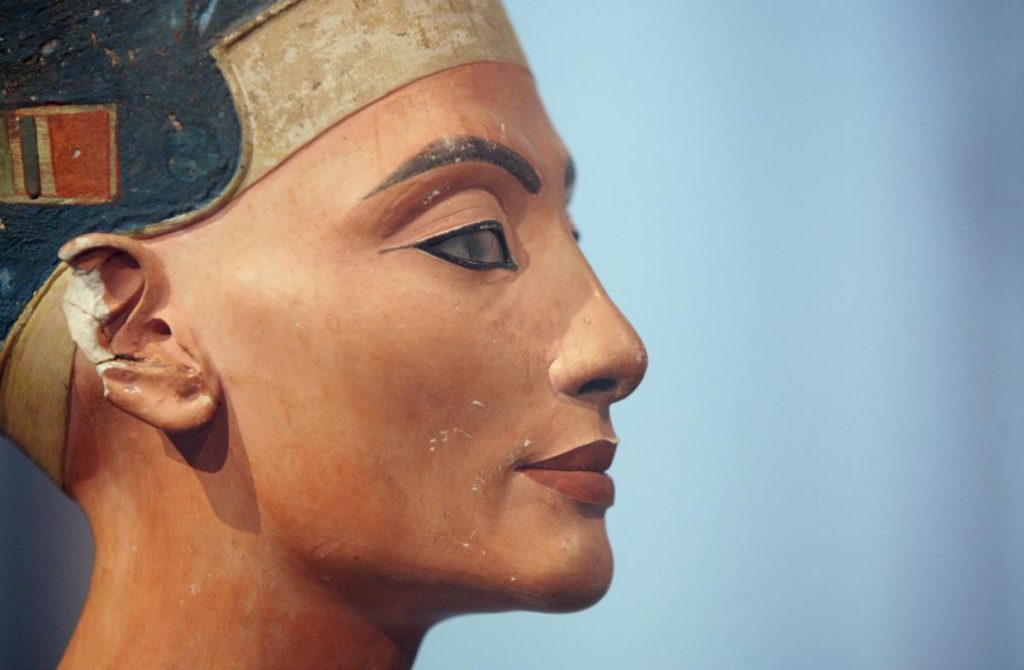

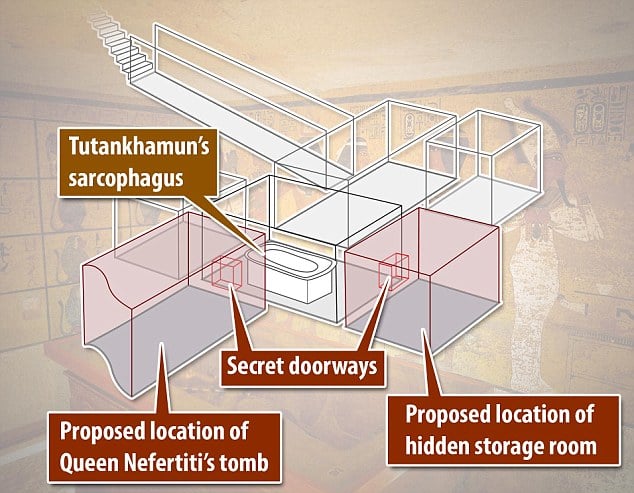

A diagram of King Tut’s tomb showing the suspected locations of Nefertiti’s tomb. Image courtesy of Nicolas Reeves.

Egyptologist Nicolas Reeves thought he had it all figured out. Studying high-tech scans of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, he saw the faint outlines of a sealed-up doorway. The boy king’s tomb had always seemed small for the splendor it contained, and there was a mix of different iconographies in the grave’s goods. Perhaps, the tomb and its contents had originally been meant for somebody else, hastily converted when Tut died young?

In 2015, Reeves published a spectacular theory: the tomb originally belonged to Queen Nefertiti, Tut’s stepmother and a pharaoh in her own right. Some the burial objects featured queenly iconography, and must have been made before her coronation as pharaoh. Reeves argued that her final resting place was just behind the stone walls, hidden under archaeologists’ noses.

The bold hypothesis captured the imagination of art historians, journalists, and archaeologists around the world, threatening to unleash a new wave of Egyptomania. Even the Egyptian government got on board, agreeing to green-light an investigation into the supposed entryways.

Initial probes seemed to indicate the presence of a hidden chamber with 90 percent certainty, but hopes of the archaeological “discovery of the century” ultimately proved unfounded. In May, the government announced that new scans definitively (and heartbreakingly) disproved the theory.