Art & Tech

Adobe Has Introduced a New Icon to Tag A.I.-Generated Images. Will It Create Transparency or More Confusion?

We asked artists and photographers if the icon addresses their concerns about authenticity and accuracy.

We asked artists and photographers if the icon addresses their concerns about authenticity and accuracy.

Adam Schrader

Adobe has created an icon into which special metadata or “Content Credentials” can be embedded, serving as a sort of watermark on a digital image to show it is “trustworthy.”

The icon was created by the computer software company with news publishers and other companies as part of an initiative of the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity, an organization that seeks to create technical standards to certify the provenance of content.

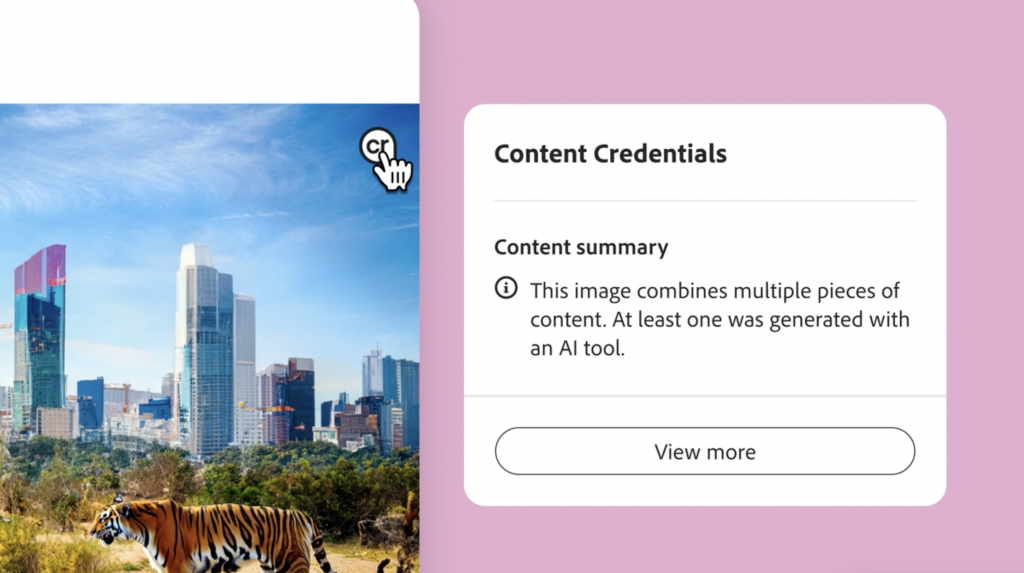

The coalition, in describing how the tool works, said users can scroll over the credentials—the icon with the letters “CR”—to reveal what it called a “digital nutrition label.” The information shown includes general metadata such as the name of the publisher or creator, as well as where and when it was created.

But the key feature that makes it stand apart from other data that can be embedded in a digital file is that it also indicates whether artificial intelligence was used to create an image, and other edits made along the way.

Adobe, in a blog post, praised corporations from Microsoft to Leica Camera that have already endorsed the tool, further highlighting it as an invisible watermark for A.I.-generated images.

Adobe’s Content Credentials or CR icon. Photo: Adobe.

But does the effort address the key issues surrounding A.I. images, particularly how they have impacted transparency and authenticity?

Cosmo Wenman, an open access activist and design consultant involved in A.I. imagery and universal access research, called it “very weird” for companies that trade in digital imagery and provenance to propose that an icon, self-certified and appended to an image, could somehow assure authenticity.

“The market prizes authenticity, but authenticity is a social phenomenon that can’t be distilled in pixels,” he said.

He pointed out the similarity of the icon to that of Creative Commons, which he believes might ironically create confusion on provenance and licensing, adding that “there’s no maker’s mark that can’t be forged by counterfeiters or abused by the brands themselves.”

For example, the artists we spoke to noted it would be simple to make a screenshot of a work and establish that as a new digital file that could in turn be manipulated, then slapped with new content credentials. There’s also nothing to stop a person from painting a copy of a painting that has appeared in a photograph labeled with the credentials, limiting its function as a tool to combat plagiarism.

An article by Fast Company further noted that the icon will be overset with a red X if changes are made to an image in which the creator had opted-in to content credentials. If changes are made to the image using software that is not compliant with the new paradigm, it would be slapped with that X the same as if all metadata was stripped from the picture or the creator opted out of signing and tracking changed with content credentials. A viewer could also see the red X and believe the image has been improperly altered.

Adding to the confusion, A.I.-generated images can also receive the credentials.

The CR icon is also intended to help viewers identify images generated using A.I. Photo: Adobe.

Photojournalists, a group that might benefit most from being able to track the provenance of images, similarly felt unsure how the tool applied to them.

Stephen Yang, a photojournalist for the New York Post, doubted the tool can do what Adobe says it can and track edits: “Not sure why you would need to do that unless you’re tracking copyrights. And, unless every site uses this tech, won’t it be useless?”

He further questioned the novelty of the tool, noting that “there have been a lot of attempts” to make similar “invisible” watermarks to help artists and photographers track down images, such as Pisxsy.

“To me this looks like an Adobe B2B [business-to-business] play where they get to charge companies to use this new ‘tool’ and maybe the odd ‘creator’ in the name of transparency and copyrights,” Yang said. “It’s a way for brands to put an ad in everything in the name of ‘transparency,’ and their pics and ads are getting ripped off online and they want to stop it.”

Daniel McKnight, another photographer for the New York Post, said he’s unlikely to use the tool and expressed that Adobe and other involved companies don’t seem to have “any real vested interest in battling misinformation in journalism,” one of the suggested possible uses for the tool.

Hovering over Adobe’s CR icon will bring up general metadata of the image. Photo: Adobe.

Some artists, however, do see the potential for Adobe’s “CR” mark in helping to curb copyright infringement.

Michael Moebius, best known for painting pop-culture icons blowing bubble gum, recently won a $120 million copyright lawsuit against hundreds of foreign counterfeiters who had stolen his work. Though not a digital creator, he often posts images of his work online like most artists. He hopes the new icon can be displayed when he shares photographs of his work on social media or elsewhere online: “I would definitely apply the mark to all of my images before publishing them.”

Moebius is now suing fast-fashion giant Shein in a suit that must establish that the infringement of his copyright happened on U.S.-based servers. Having the ability to track edits to a digital image could help in such copyright cases during the discovery process because an investigator could follow digital breadcrumbs.

Still, Moebius fears that “people who copy can get around this” and that “this will not make lawsuits too much easier.”

Artist Claudia Diroma Messica will soon head to court for her appeal of a copyright lawsuit against fashion designer Alexander Wang. Though she felt such a mark could not have prevented infringement, at least it could be a “great solution to prevent A.I. software from referencing or utilizing works without proper licensing,” she said.

She added that “the ultimate form” of protection Adobe could give artists and photographers who use its products would be to allow the metadata to communicate with software that a file cannot be altered from its original state, much like a locked PDF document.

“Imagine if a .jpg was transformed into a different file extension [like] .crp and you can only view the image but you are unable to screenshot, import, or open the file anywhere, only view it,” she suggested. “Perhaps the media has an expiration date on it and you can only view it for a certain amount of time(s): ‘expire-able media.’”