Art World

‘This Exhibition Is a Provocation’: Curator Adriano Pedrosa on His Vision for the Venice Biennale

Venice Biennale curator Adriano Pedrosa on the myth of the foreigner and the weight of making less visible narratives visible for new audiences.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity—to hear the full version, tune into The Art Angle.

This is the first biennial to be organized by a curator who openly identifies as queer, the first to be helmed by a curator from Latin America, and the first to be led by someone who’s also based full-time in the Global South. This is also the largest representation of queer and Indigenous art in the Venice Biennale’s history. These are major milestones—I imagine they bring with them a sense of pride and also an amount of pressure to get it right.

It is interesting that you mention pride. I always saw it as a huge responsibility because of all that—because of being from Latin America, from the first curator actually living in, based in the global south—after, of course, the first curator from the global south, the late and great Okwui Enwezor who curated the Venice Biennale exhibition in 2015, although he was based in Germany at the time and working in Munich.

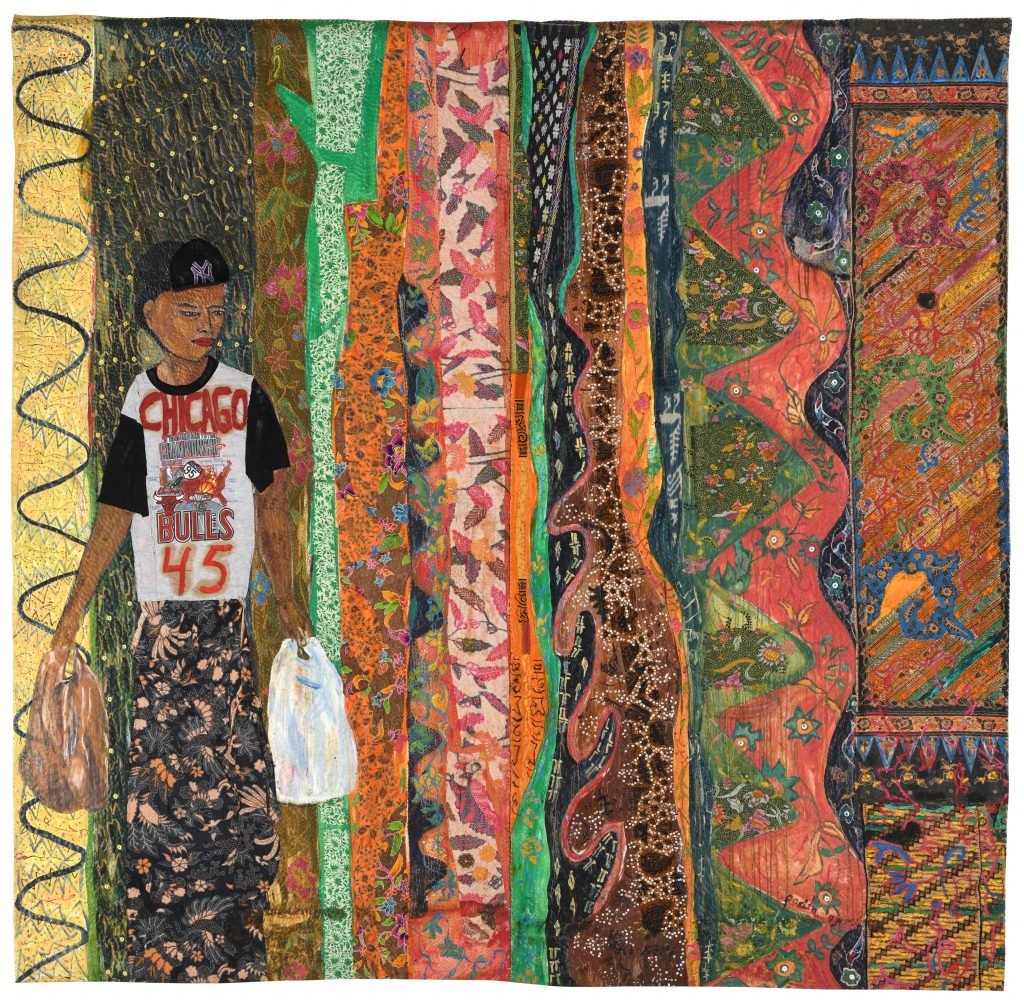

Pacita Abad (Basco, Philippines, 1946 – 2005) You Have to Blend in before You Stand Out (1995) Image courtesy of Pacita Abad Art Estate / Photo by Peter Lee

I thought about the Biennale quite strategically. The Biennale is arguably the most important biennial, and perhaps the most important platform of contemporary art and certainly the one that draws more visibility to the works and to the artists.

I do understand that it’s much easier than it was for most of the 20th century for foreign artists from the global south to participate in a large scale international exhibition. You can’t organize a biennial or a large scale global art show without artists, say, from Mexico or Nigeria or India or Turkey, or Brazil or Argentina or South Africa for that matter. These artists are always present in these exhibitions, but that doesn’t happen so much with artists that were working in the 20th century. That’s why I thought it was interesting not only to develop the nucleo contemporaneo as I call it, which is focused in four subjects: the foreigner, the Indigenous, the queer, and the outsider, but also a nucleo storico that looks at modernisms in the Global South and artists working in the 20th century in the global south.

Rómulo Rozo (Chiquinquirá, Colombia, 1899-1964, Merida, Mexico) Bachué, Diosa Generatriz (1925), Granite sculpture. Courtesy Proyecto Bachué, Colombia.

These artists are canonical figures in Egypt or South Africa or Nigeria or Pakistan or Ecuador or Colombia, but they are not well known internationally and they didn’t have the chance to participate in the Biennale. In a way, it’s almost as if the Biennale is paying a debt towards these artists.

These thematic clusters, these nuclei—those who know your curatorial work will recognize that you’ve taken a similar approach at the São Paulo Museum of Art, MASP, which you lead, with an ongoing series of exhibitions called “Histories.” Can you explain what these shows are? What kind of overlapping approaches can we look for in Venice?

At MASP, where I’m artistic director, we have been organizing our exhibition program since 2017 dedicated to a full set of histories: sexuality, feminist histories, Afro-Atlantic histories. Last year we did Indigenous histories, and this year we have a full year devoted to queer histories. Some of these themes have come up and are coming up in our program in Venice, most notably Indigenous histories.

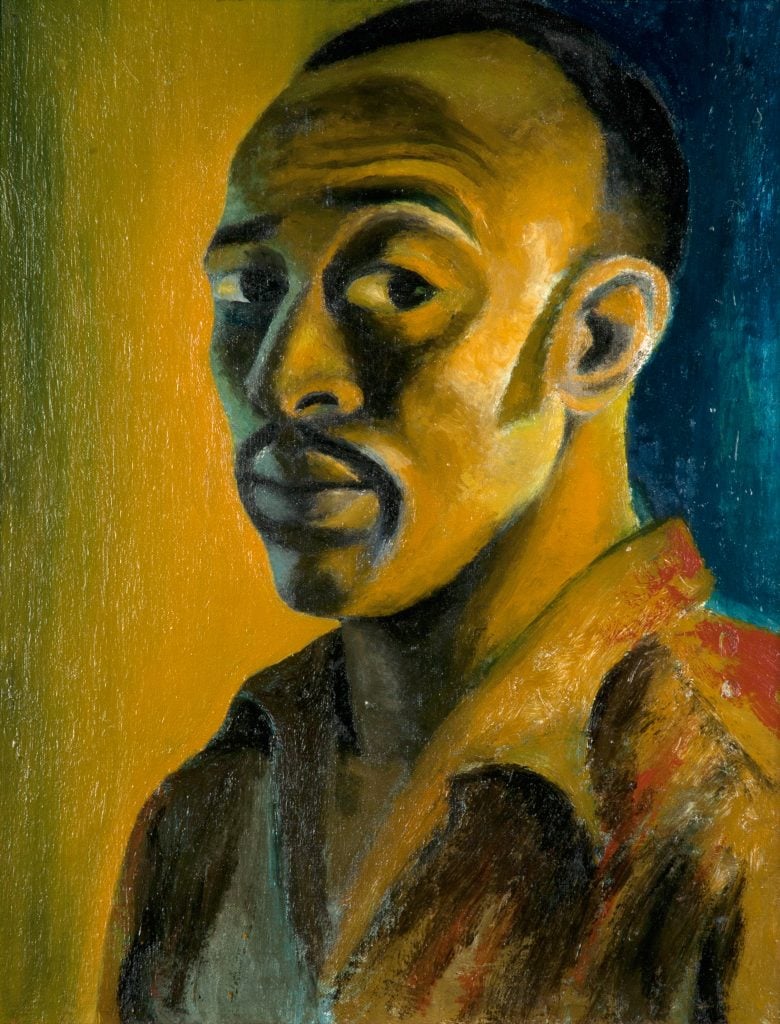

Afro-Atlantic Histories was a very special year for us. We looked at relationships between Africa and the Americas through the Atlantic. Some of the same works will be in the nucleo storico—like, for example, Barrington Watson, a Jamaican artist. We have Gerard Sekoto, a South African modernist.

Gerard Sekoto (Botshabelo, South Africa, 1913-1993, Nogent-sur-Marne, France), Self Portrait (1947). Photo Kristian Tobin Photography / The Kilbourn Collection

I should say that this nucleo storico hearkens back to another project that I worked on in 1998, in the Sao Paulo Biennial when I was a very young curator, invited to work with Paulo Herkenhoff, who is a very important curator in Brazil, in what is considered one of the most iconic editions of the Sao Paulo Biennial. That exhibition also had a historical segment, “Antropofagia,” which is an important concept within Brazilian modernism that I’m using as a possible tool to look at Modernisms in the global south.

Biennials are typically a referendum on the now. But this idea of the contemporary, as you note, leaves out many people who did not have a chance to be visible before. What do you hope to achieve by working with different sense of timeliness?

I think a biennial is mostly devoted to contemporary art, but I’m coming from a history in Sao Paulo where there were often historical segments and historical positions in the exhibition itself. These histories are quite relevant and very exciting. What I’m trying to do is almost a speculative curatorial exercise. It hasn’t really been done. It’s a draft, it’s an essay, it’s a provocation. It’s definitely not a definitive sort of encyclopedic presentation of a vast topic such as modernism in the Global South. I do feel that Venice does give us an opportunity to reinvent something and propose something quite ambitious because of the enormous energy that it gathers. There’s an exceptional kind of unique visibility, and this is what these artists really need.

Claudia Andujar (Neuchatel, Swisstzerland, 1931 – Lives in São Paulo, Brazil) Yanomami – da série A casa (1974) © Claudia Andujar / Courtesy Galeria Vermelho

There are some connections between what Cecilia Alemani was trying to do and what I am trying to do. She had historical positions as well with a completely different, wonderful, and relevant approach with her capsules. I am with this idea of the nuclei in quite a different manner, but we do have this interest in a certain rewriting of art history. I don’t think I’m rewriting art history, but I am proposing to question more established narratives of art history.

This exhibition is a provocation; other people, institutions, or scholars might want to unfold this and take it elsewhere. I think this is very exciting and very contemporary.

I’m curious about how you researched and edited an exhibition of this size. Alemani had a very unique challenge—she had to do this during the pandemic. I imagine you were able to do a lot more mileage and travel.

Yes. The global self is much bigger than the Global North. I don’t think you can face a project like this and think that you will be visiting all these places. I visited a few places for the first time—Luanda, Hara, Nairobi, Santo Domingo, and Guatemala. There were some very specific places that I had not been, but other than that, mostly I was returning.

Returning to Beirut, Istanbul, Hong Kong, to Manila, Jakarta. I think it’s much easier to return, even if you have only a couple of days. You have that history of being in that place. So it became easier for me to compliment this with new research. While the exhibition does have quite a lot of artists, the checklist is a little bit deceiving because we have a larger number of artists in the nuclei storico than in the nuclei contemporaneo. But in the nuclei storico, each artist is present with one single work only in these three sections. When you look at the list of artists, it’s a bit deceiving because it doesn’t correspond to the reality of the exhibition and the presence of the works in the space.

Lorna Selim (Sheffield, United Kingdom, 1928-2021, Abergavenny, Wales) Unknown (1958). Courtesy Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art / Photo Hamad Yousef

The last edition, while there were fewer artists, there were many more works. So for us, the density of the exhibition in the space, in terms of volume, won’t be as much as it was in the previous edition.

Can you give some insight into the name of the exhibition, “Foreigners Everywhere”? I understand that you’ve had it in your mind for many years.

Claire Fontaine is in the show and they collaborated on the design and merchandise. We do a lot of back and forth and collaboration—I’ve been working with them for more than 15 years. They appropriated the name of a collective that was fighting racism and xenophobia in Torino in the beginning of the 2000s. They’ve been doing a series of neon sculptures since 2004 that [contain] the expression foreigners everywhere in many different languages. They will be presented in a large scale installation in Venice.

Claire Fontaine (Founded in Paris, France, 2004 – Based in Palermo, Italy) Foreigners Everywhere – Spanish (2007) Photo by Studio Claire Fontaine / © Studio Claire Fontaine / Courtesy Claire Fontaine and Mennour, Paris

The expression itself has been in my mind for a long time. In 2009, I was invited to curate an exhibition at the Modern at Sao Paulo. I thought it was interesting to do something more provocative and speculative, and my proposition was that Brazilian contemporary art was not solely made by Brazilians. It could be art made by foreigners that had Brazilian references or content. It was very polemic project. I was accused of not including Brazilians. In that project, I had a small residency with maybe six or seven artists and Claire Fontaine was invited. There, they did two neon sculptures, one foreigners everywhere in Portuguese and a second sculpture was made in old Tupi, an extinct language Indigenous Brazilian language. The title became the subtitle of the exhibition. It was completely different exhibition—completely different in scale and approach—but with the same title.

In 2011, I was looking around the Venice Biennale and thinking how difficult it must be to come up with a framework and a title with that specificity but is generous, and also palpable. This is my humble opinion, but I find that most biennials, they usually have either quite poetic names or cryptic titles. They’re not very didactic or very generous, or they do not provide a lot of specificity. There are these wonderfully poetic titles that everything could fit under. It is more interesting to come up with something that has some complexities—the poetic dimension, political dimension—but also to be generous and give hints to the audience and what they will encounter.

To hear the rest of this interview, tune into the full episode on The Art Angle.