Art & Exhibitions

With ‘Afro-Atlantic Histories,’ the Often-Staid National Gallery of Art in Washington Finally Acknowledges Contributions It Long Ignored

“Afro-Atlantic Histories” is like nothing else ever shown before at the National Gallery.

“Afro-Atlantic Histories” is like nothing else ever shown before at the National Gallery.

Kriston Capps

For a week in May, the sculpture garden at the National Gallery of Art was the noisiest spot in the U.S. capital.

Each afternoon, a steam-powered carnival organ designed by Kara Walker huffed and puffed on the National Mall, drawing curious crowds. Her piece, The Katastwóf Karavan, is a calliope, a mechanical organ once common on the steam engines that lumbered up and down the Mississippi River. The cacophony is broadcast from a parade wagon wrapped in steel silhouettes depicting the artist’s storybook scenes of antebellum nightmares.

Kara Walker, The Katastwóf Karavan (2017). Installation view: Prospect 4: The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp, New Orleans, 2018. Photo: Alex Marks © Kara Walker.

The sour melody piping from Walker’s contraption cast a spell over onlookers. More so than its traffic-stopping appearance at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2019—more so, even, than its magical debut at the Prospect 4 triennial in New Orleans in 2018—The Karavan’s disruptive, dyspeptic residency in DC marked a turning point for its venue. Walker’s work came to the city as part of “Afro-Atlantic Histories,” a consequential show for one of the most staid institutions in Washington. Perhaps no longer.

“Afro-Atlantic Histories” is like nothing else ever shown before at the National Gallery. With artworks dating from the 1700s to the present moment, it traces the paths of the African diaspora as enslaved peoples arrived in the Americas and pursued their liberation. The exhibition couples collection items alongside contemporary acquisitions as well as Indigenous works, including objects that the National Gallery might not have acknowledged as art only a few years ago.

For the first time, a museum that has been silent on so many of these fronts in art history—or art histories—has decided to get loud.

The show opens with A Place to Call Home (Africa America Reflection) (2020), a mirror by Hank Willis Thomas shaped like a Western hemisphere from an alternate Earth, with the North American continent tethered to Africa by way of Central America.

The entrance to “Afro-Atlantic Histories” at the National Gallery of Art with Hank Willis Thomas’s A Place to Call Home (Africa America Reflection) (2020) in the background.

This is one of several new acquisitions by the National Gallery for its presentation. Other new permanent-collection works in the show include a totem by Daniel Lind-Ramos of Puerto Rico and a drawing by Njideka Akunyili Crosby of Lagos. A striking, monumental, ebony portrait by Zanele Muholi (Ntozakhe II, (Parktown) from 2016, also new to the collection, can be seen all over town in promotional ads.

Zanele Muholi, Ntozakhe II, (Parktown) (2016). © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of the artist, Yancey Richardson, New York, and Stevenson Cape Town / Johannesburg.

While these contemporary works are welcome additions for a museum with a laserlike focus on the canon, “Afro-Atlantic Histories” makes its strongest case through 18th- and 19th-century portrait and landscape works. This ought to be firmer territory for the National Gallery, but “Afro-Atlantic Histories” finds the museum on new footing.

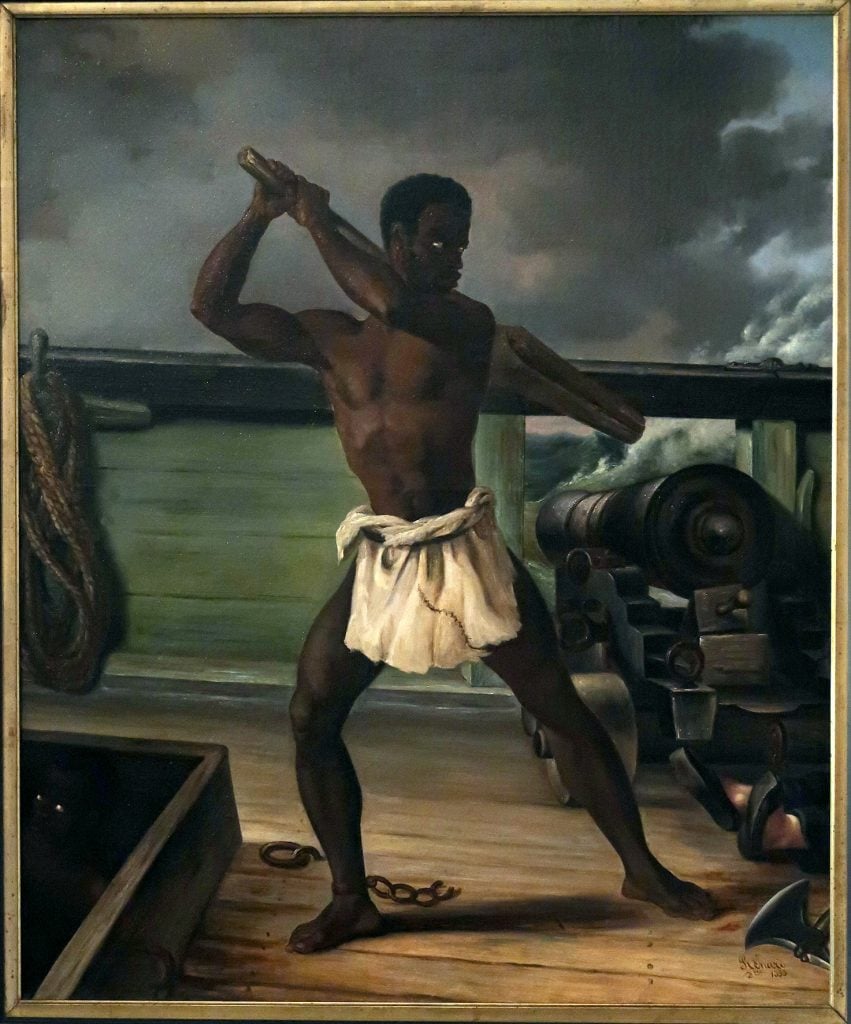

Édouard-Antoine Renard’s Slave Rebellion on a Slave Ship (1833) depicts a heroic Black man holding a mighty oar as if it were a baseball bat, the feet of a white slaver decked out beneath him. Nathaniel Jocelyn’s Portrait of Cinqué (1839–40) is a rich contemporaneous portrait of the Mende farmer who led the revolt on the Spanish slave ship La Amistad. Alongside these idealized paintings are more ambivalent scenes, such as George Morland’s European Ship Wrecked on the Coast of Africa (1788–1790), which shows benevolent Africans saving distressed Europeans, as well as Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s The Last Sale of Slaves in St. Louis, Missouri (1880), a picture of social stagnation in the heartland. Fantasy, testimony, and other ideas on view, sometimes side by side, help to ground the concept of competing histories, plural.

Edouard Antoine Renard, A Slave Rebellion on a Slaveship (1833). La Rochelle, Musée du Noveau Monde, France.

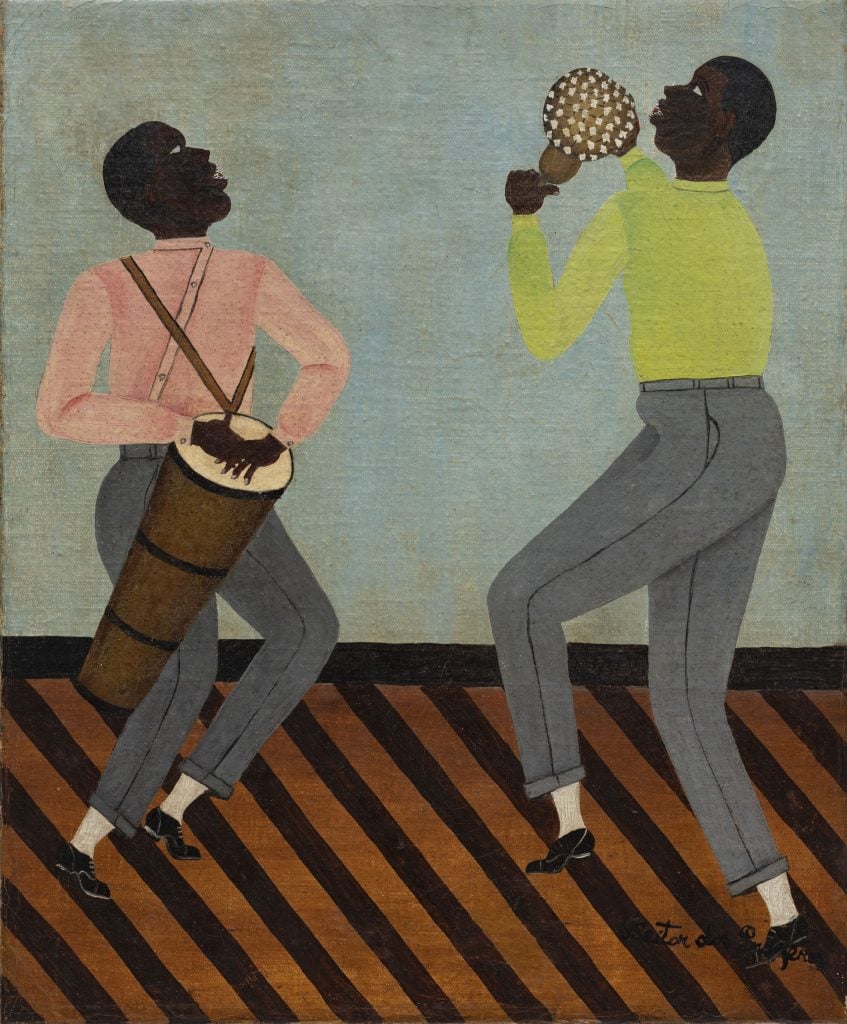

Originally organized by the Museu de Arte de São Paulo and Instituto Tomie Ohtake in Brazil, “Afro-Atlantic Histories” has been adapted for presentations in the U.S. at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (where it was on view from October 2021 to January 2022) and the National Gallery (on view through July 17). From the Museu de Arte come flattened figurative oil paintings by Heitor dos Prazeres of Afro-Brazilian work and play, while the MFAH contributions include paintings on cardboard of Louisiana plantation life by Clementine Hunter. As much as anything else in the show, these self-taught artists challenge and expand the histories that the National Gallery has sought to elevate in the past.

It would not be too strong to say that the National Gallery’s presentation of Black figurative artworks feels contemporary—hip even. The showcase of mid-century paintings by dos Prazeres, Horace Pippin, Hayward Oubre, William H. Johnson and other outlier artists aligns with similar gestures elsewhere, whether that’s Azikiwe Mohammed’s deskilled-looking installation across town at Transformer or Célestin Faustin’s inclusion at this summer’s Venice Biennale. In the art world, there’s always something in the water; the National Gallery is just usually nowhere near it.

Heitor dos Prazeres, Musicians (1950s). Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand.

The shift at the museum starts with staff. At the top of the org chart is Kaywin Feldman, who made “Afro-Atlantic Histories” a priority upon her arrival as director in 2019. She hired Kanitra Fletcher, the museum’s first curator of African American and Afro-diasporic art and organizer for the exhibition’s U.S. tour. (Fletcher also brought the Tate Modern’s “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” exhibition to Houston.) In addition, the National Gallery appointed Steven Nelson, professor of African and African American art history at the University of California in Los Angeles, as dean of the museum’s prestigious Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts. Joining them is Eve Straussman-Pflanzer, the new curator and head of Italian and Spanish paintings, among scores of other recent hires.

Appointing a feminist art historian to run the Southern European paintings department or naming a curator to bring the African diaspora into the collection might seem like planting seeds for future growth. But changes are already happening. The National Gallery just acquired a painting of a noblewoman by the 16th-century Mannerist artist Lavinia Fontana, perhaps the West’s first professional woman artist. It picked up a second piece by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, the first Native American painter in the National Gallery collection. And the museum is aggressively acquiring works by Black artists, among them Genesis Tramaine, Marion Perkins and David Driskell. (The National Gallery would not confirm the acquisitions of Fontana or Perkins.)

This is a reversal from a dismal record that stretches back decades. Recent shows spotlighting Oliver Lee Jackson and Lynda Benglis (curated by Harry Cooper and Molly Donovan, respectively) represent two of just a handful of exhibits by living artists who are women or people of color. The story isn’t much better for marginalized artists of the past.

“Afro-Atlantic Histories” can only tell so much about the National Gallery’s trajectory. It’s not a perfect fit for the museum, or for the U.S. It’s shallow on Afro-Latino artists from Haiti and Cuba: Rigaud Benoit, Wilson Bigaud and Wifredo Lam didn’t make the cut for the U.S. tour. While the exhibit proceeds both thematically and chronologically, by the end, it sprawls. A painting of the Emperor Haile Selassie by Ethiopian painter Alaqa Gabra Selasse, for example, doesn’t seem to fit the theme.

But the show has already demonstrated what a new outlook for the National Gallery could mean for the museum, and for Washington. Incoming U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson toured the exhibition. So did the Obamas. The National Gallery has yet to produce an original show under the imprimatur of its new director, Feldman, but with a startlingly relevant first outing, the museum is already making noise.