Art History

What Does It Mean to Be an Afrofuturist Now? Three Contemporary Artists on What the Term Means to Them

Alisha Wormsley, Mequitta Ahuja, and Cauleen Smith all help move the conversation beyond Black science fiction tropes.

Alisha Wormsley, Mequitta Ahuja, and Cauleen Smith all help move the conversation beyond Black science fiction tropes.

Melissa Smith

A lot of people came to learn about Afrofuturism without knowing it was Afrofuturism at all—they were just looking for a lifeline. They were trying to conceptualize Blackness for what they knew it was. And could be. They found themselves in “inhospitable places,” said artist and professor Sherwin Ovid, and wanted “to create a space to breathe.”

In a 1993 essay called “Black to the Future,” cultural critic Mark Dery coined the term “Afrofuturism” to cover a set of ideas that had been championed by three people he interviewed for the piece: cultural critic Greg Tate, science fiction author Samuel Delaney, and music scholar Tricia Rose. Those three were also instrumental in establishing a broader community for a sensibility that had otherwise mainly circulated in the music industry, associated with progenitors like Sun Ra and George Clinton.

As much as Afrofuturism can be defined, its principles coalesce around a shared commitment towards resistance to societal tropes associated with Blackness, using a type of “science fiction that is fact-based,” artist Cauleen Smith recently told me, to pull from “the past, or people in the past, to speculate and offer models for the present and future.”

That said, it’s important to stress that not all narratives relating to speculative futures equal Afrofuturism—and vice versa. In the present, as Ovid explained to me, we seem to be “living in the horizon of what many of those [progenitors and others] would have imagined”—so how does Afrofuturism find meaning with artists today?

Alma Thomas shown with two of her paintings that were part of an exhibition of her work at Howard University Art Gallery in Washington, DC, on April 20, 1966. (Photo by Ellsworth Davis/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

In many ways, Afrofuturist art and thought is a reconsideration, a re-imagining of history—in both directions. For her book Charting the Afrofuturist Imaginary in African American Art, Dr. Elizabeth Hamilton decided to look to the past to establish “a lineage for [Afrofuturism] that wasn’t based in music,” she said. She cites artists like Harriet Powers (1837-1910), who “imagined other worlds outside of 19th-century Georgia, with celestial patterns within her quilts that are like star charts,” and painter Alma Thomas (1891-1978), who often gave her abstractions titles that referenced outer space like Starry Night and the Astronauts (1972).

The term “Afrofuturism” had yet to exist in these artist’s lifetimes, and it’s an open question as to whether or not they would have thought it even fit. For more recent examples, Hamilton sees resonances with Afrofuturist thought in contemporary work from a range of artists including Sanford Biggers, Robert Pruitt, and Renee Cox—many of whom explore Afrofuturism as a discipline “founded on Black feminist thought,” Smith told me.

In Dery’s essay, he asked: “Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of that history, imagine possible futures?” Artnet News spoke to three artists who have dedicated part of their practices to wrestling with this question, and so can be said to explore what a contemporary Afrofuturist project looks like. They’re artists who have helped to give form to a movement that, despite what Black Panther would have people believe, was, according to Smith, never actually meant to be one.

Alisha Wormsley. Image courtesy the artist.

Artist Alisha Wormsley is not sure she’d call herself an Afrofuturist—but she is a self-proclaimed “Black person who is into imagining futures,” she said, as a way of “reclaiming our own things.”

Science fiction often has been treated as the ideal vehicle for Afrofuturism’s reappraisals. Around 2011, Wormsley was working on science fiction films with Black characters in them. Her friend Ingrid LaFleur then introduced her to the possibility that these works could be characterized as “Afrofuturist.”

About that time, Wormsley was making a short film called Children of Nan: Beginnings about an “apocalyptic future where there’s only white men and Black women left on the planet and they’re at war,” she explained. The film used material from her Children of Nan archival project, which consisted of “all these things I’d collected about Black women around the world, and across time.”

Alisha Wormsley, Children of NAN: Chapter 1, beginnings (2011). Image courtesy the artist.

When she moved back to her hometown of Pittsburgh in 2012, Wormsley continued to pursue ideas that overlapped with what many consider to be the core tenets of Afrofuturism: technology, mysticism, liberation, and the Black body.

In 2013, she curated a Black film and performance series, called “Afronaut(a),” which brought in groups like Black Radical Imagination, a touring platform that screened films informed by Afrofuturism, Afro-surrealism, and magical realism.

When Wormsley was then asked to participate in a panel discussion on Afrofuturism in 2014, she called Greg Tate to learn even more, she recalls. All the while, Wormsley was also developing projects around a slogan that struck a chord exactly for just how basic it is: “There are Black People in Our Future.”

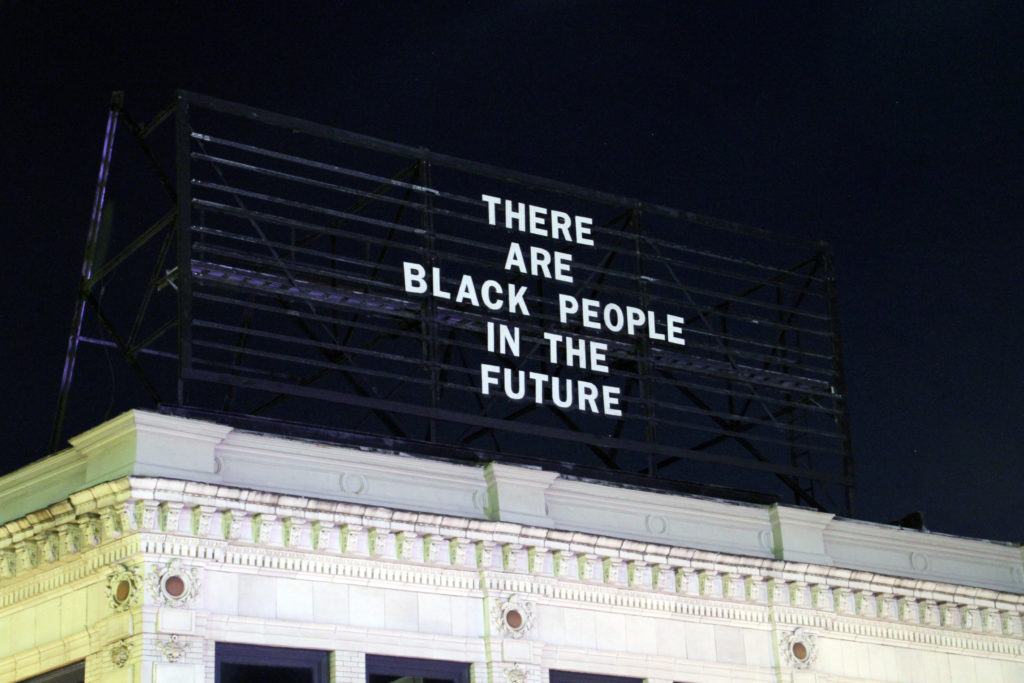

Alisha Wormsley’s contribution to The Last Billboard project in Pittsburgh. Photo courtesy of The Last Billboard project.

She came up with the line after her students who lived in and around the Homewood section of Pittsburgh told her they considered the neighborhood an ideal location to shoot a zombie film. Howewood was once where “the first Black opera started,” Wormsley explained, but had since become more and more deserted. By deciding to plaster the slogan all over that area, the artist was bringing attention to the obvious fact that Black people are being erased from both the present and future—or at least the futures “conceived by white people,” as Cauleen Smith said of Wormsley’s work.

Eventually, Wormsley was commissioned to put the slogan on a billboard in a gentrifying neighborhood in Pittsburgh called East Liberty (which caused a stir after the landlord of the building asked that it be taken down.)

In college, Wormsley had been an anthropology major. At the time, she read The Sanctified Church by Zora Neale Hurston. In the book, Hurston described visiting Black houses of worship. “Hurston was really into when people would speak in tongues—she called it shouting,” Wormsley said. “And she talks about how she found traces of African dialects in that shouting.”

This is a way to point out that, in the same way that Black people are using Afrofuturism to “liberate themselves from white supremacy so we can imagine more freely,” Wormsley told me, they also refuse to be held captive to the concept of time itself. That “different sense of time,” the artist continued continued, “shows up in everything that we do. So I feel like Afrofuturism can be very specific. Or it’s everything.”

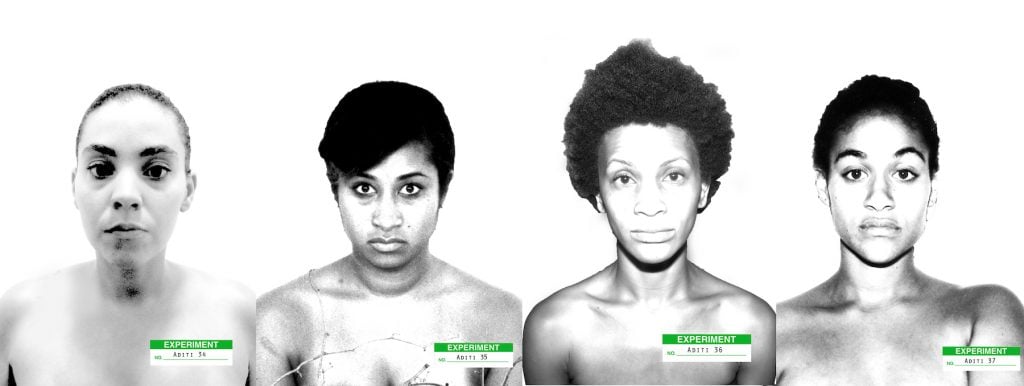

Mequitta Ahuja, 2021. Photo by Nicholas Riley Bentham.

“I think my own reasons for maybe not using the word myself,” said painter Mequitta Ahuja, “is I see it as included in this history of science fiction and Black science fiction writers.”

And it certainly has been. But not always.

In “Black to the Future,” author and “grandmaster of Afrofuturism,” Samuel R. Delany, said this: “The historical reason that we’ve been so impoverished in terms of future images is because, until fairly recently, as a people, we were systematically forbidden images of our past.”

To describe her portrait work, Ahuja has often used the term “automythography” (which is a variation of biomythography, a term coined by Audre Lorde that, as the etymology suggests, describes the combination of myth, history, and biography.) She considers it a tool in becoming more aware of “who we are.” To her, imagination and self-invention are a critical part of undoing that denial of past images.

The history of Black people is unknown, but doesn’t have to be unknowable. So Ahuja is out to create, through avenues real and imagined, “a continuity of the past, present and future,” she said.

In Ahuja’s recent show, “Black-word,” she used letters and archival material that she’d uncovered from research into her ancestry to “picture the ancestors for whom I don’t have photographs.” She then created those faces from the faces she did know, in a part-fact, part-fiction exercise that seems straight from Afrofuturism’s playbook.

In Charting the Afrofuturist Imaginary in African American Art, Hamilton looked at Afrofuturism’s relationship to mythmaking, and how artists like Ahuja have also used “transformations of the hair,” she explained, as “a way of taking back the Black female body and making it superior.” So even though Ahuja knows “automythography is not Afrofuturism per se,” she said, she “thinks it fits within this framework of combining different elements to create the whole picture.”

Cauleen Smith. Photo by Joshua Franzos.

“Sometimes I’m hesitant to participate in conversations around Afrofuturism, because I am not interested in a lot of what it has produced now,” Smith told me, “which to me is so, so much about the way people want to fashion themselves, as opposed to conversations about proposals for living.”

As a blueprint for life, “Afrofuturism has so much to do with a relationship to technology,” Smith continued, “which has so much to do with the way in which Black people were deployed as human machines and attempting to understand how that plays out in the present, and what it might look like in the future as a way of getting control over these very heavy shadows of psychic trauma.”

Smith was a film student at UCLA when she stumbled upon the afrofroturism.net website. It was 1994, and she was looking to “read or find people trying to think about how to produce images of Black people that really resisted the mainstream commercial structures that we had to operate within,” she recalled. There, she found a group of people coming up with strategies to do just that.

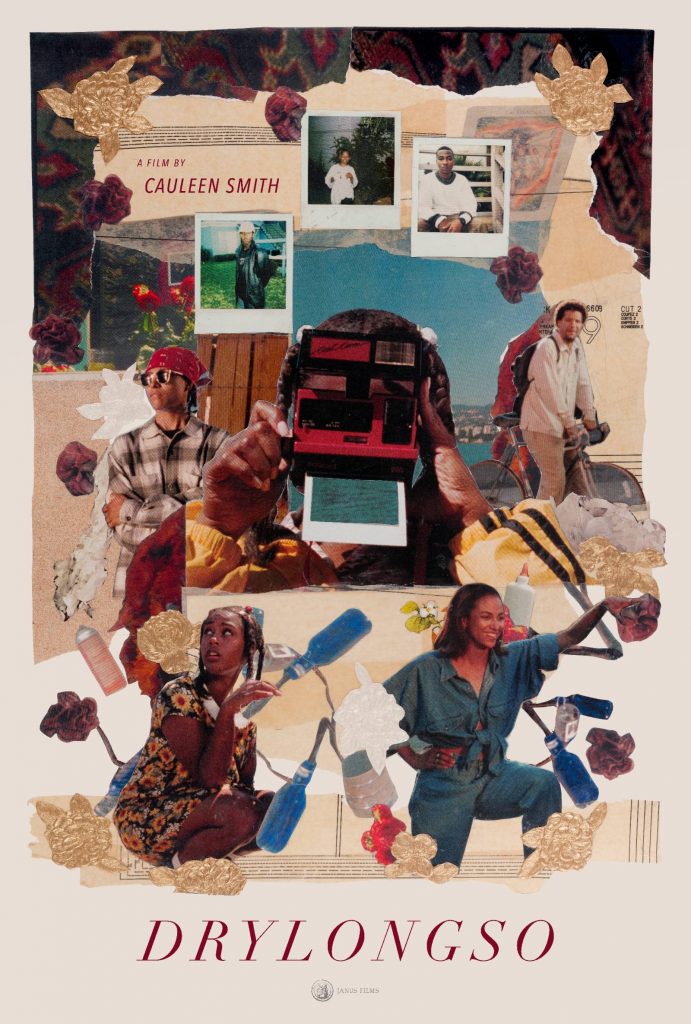

After making a film about “leaping back and forth into different identities,” Smith remembered, Greg Tate explained to her that she already had been developing such strategies herself. (Smith’s 1998 indie film Drylongso has just now been restored and is getting a theatrical re-release.)

Poster for Cauleen Smith’s Drylongso (1998).

Smith has been a devotee of Afrofuturism ever since, dedicating many strands of her work, mostly in the form of experimental films, to exploring how to reject trauma narratives in favor of imagining something different—something utopian, even, for Black people.

Even so, Smith has never truly claimed to be a spokesperson for Afrofuturism.

For her, the moment that Afrofuturism “can be branded, or someone has appointed themselves as a spokesperson for that conversation, is my cue that it isn’t viable anymore,” she says. Back when she happened upon the term, “the whole point of it was that it was a conversation, and that it wasn’t defined.”

Similarly, in our conversation, Ahuja described a similar fear of being categorized. When things get defined, even as just “Black,” it sometimes becomes “hard to maintain a sense of community or shared ideology, without it becoming so narrow.”

In that way, these contemporary artists are working with Afrofuturism in the tradition of how Smith remembers first discovering it—as a conversation and a place to call home.