Art World

‘Time’ Magazine Says Contemporary Art Is to Blame for Trump. That’s Stupid.

Alex Melamid issues a bold and baffling denunciation of cultural "infantilism."

Alex Melamid issues a bold and baffling denunciation of cultural "infantilism."

Ben Davis

This week, Time has graced its Ideas section with an opinion piece exhorting readers to “Blame Donald Trump’s Rise on the Avant-Garde Movement.” The artist Alex Melamid penned the essay. He’s currently publisher of Artenol magazine and formerly one half of witty conceptual art duo Komar & Melamid, which might lead you to think that this was some kind of satirical experiment. Except I don’t think it is.

Even judging by the extremely low bar set by cultural hot takes on Trump, this one is an oddity.

To paraphrase, it starts in the 1960s and is about how Andy Warhol made publicity and money cool. Ergo, Warholian values are to blame for the fact that we have a president who’s all about publicity and money. That’s probably overstating the case, even if it is true that Warhol is the one artist that Trump seems to know by name.

But Melamid does not stop there. He jumps back in time to Dada maestro Tristan Tzara and Cubist king Pablo Picasso, arguing that these modern artists cleared the way for the rise of a general cultural “infantilism” that has now touched the highest heights of power.

He then rounds back towards the present:

Recent artists have taken the idea further. Jeff Koons’ “Play-Doh,” a gigantic sculptured pile of the familiar childhood substance, has been dignified by the New York Times’ Roberta Smith as an “almost certain masterpiece.” (Koons also just released a new sculpture in Rockefeller Center; it is a balloon.) Cy Twombly’s pieces look as if they were made by a four-year-old; Howard Hodgkin’s are hardly more sophisticated. Looking at the work of Warhol’s protégé Jean-Michel Basquiat, hailed by many as the greatest artist of the last fifty years, one might be forgiven for assuming it’s the product of a disturbed nine-year-old—and a lot of parents will tell you that nine is a bad age, destructive and freewheeling, in a peculiarly American sense.

Leaving the political stuff aside for a moment, let us pause to say what a weird list of artists this is. You don’t ordinarily group, say, Hodgkin’s lush old-school abstraction with Koons’s slick neo-Pop.

The late Howard Hodgkin (1932–2017) with a suite of his paintings, in 2008. Photo by Cate Gillon/Getty Images.

To lump them together as evidence of a general “infantilism” seems itself pretty immature: Surely the adult way to approach art is to grant each artist the dignity of a more-than-superficial reading.

In any case, you get the idea: Mainstream art is childish, which has filtered out to make the world childish. (While he’s at it, Melamid pins the present epidemic of superhero movies on the “avant-garde” influence too. Why not?)

“Whatever the intelligentsia nurtures and celebrates in our galleries and academic journals is bound to flow eventually into the nation’s cinemas, through its ballot boxes, and toward the swamp of Washington, D.C.,” Melamid writes, closing the case.

It would actually be very comforting if this were true, to believe that art had that kind of prophetic power!

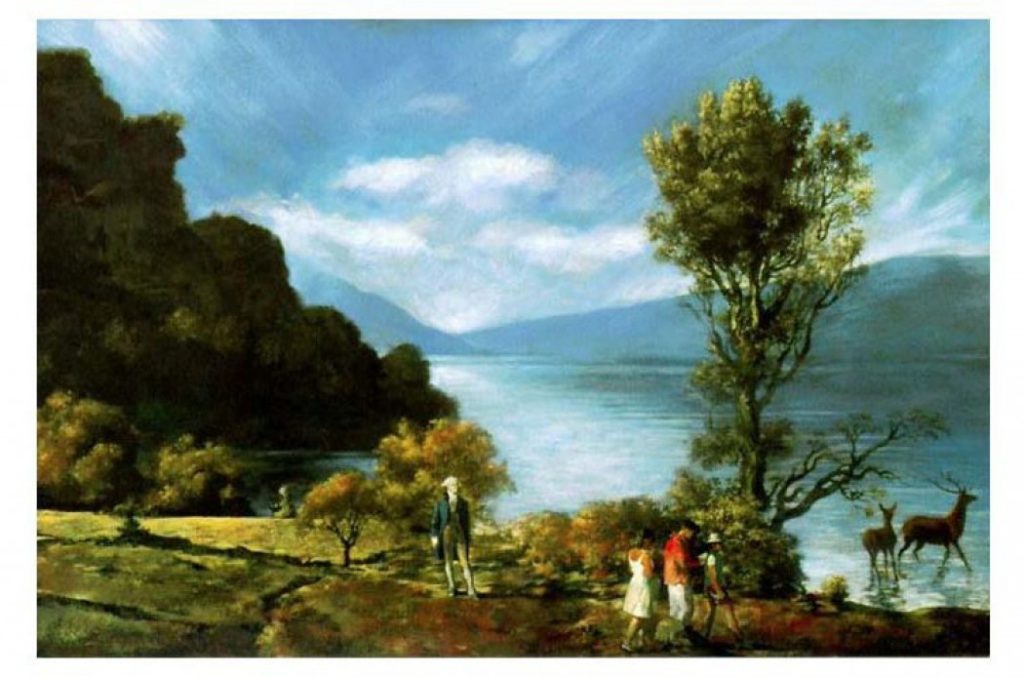

Komar & Melamid’s version of the USA’s Most Wanted painting. Image courtesy of DIA Foundation.

The oddest thing is that, as part of Komar & Melamid, Alex Melamid made his name with the project The People’s Choice (1994–1997). For that famous work, the duo did opinion polling in a variety of countries about artistic taste. Based on the responses, they then had a painting fabricated that would be, theoretically, the perfect artwork to match each country’s taste.

What did popular taste look like? Well, the “people’s choice” was definitely not avant-garde, usually some kind of watery Impressionist-inspired realist landscape, with a familiar historical figure near a lake and lots of blue (This formula was true of all the surveyed nations except, randomly, for Holland, whose “most wanted” painting is an abstract composition of color swatches.)

What does The People’s Choice show, in its knowingly campy way, except that popular consciousness is actually rather segregated from anything remotely approaching the “avant-garde movement”?

The political situation is dire. Nothing really feels important right now unless it somehow connects to that situation, which leads to all kind of flailing around in cultural commentary. In this case, turning the problem inside out, Melamid ends up echoing the most thoughtless caricature about modern art—”my kid could do that!”—just to construct a credible way to plug art into the Conversation about Trump, who acts like a kid.

I’m not saying that there is no blame to be shared by the “intelligentsia,” or their “galleries and academic journals.” It’s just I think it is mainly to be found in how out of touch that conversation is; how it constructs a bubble with a puffed up sense of its own universality; how it doesn’t really touch on the world, not how it does.

Despite being wildly sloppy, Melamid’s argument seems to have some traction. Why? I think maybe because it recreates a false sense of self-importance in the guise of criticizing it—fake news disguised as real talk.