Art & Exhibitions

How Calder Inspired the Gravity-Defying Sculpture of Thaddeus Mosley

At the Seattle Art Museum, an unexpectedly satisfying dialogue between two distinct ideas of shaping space.

At the Seattle Art Museum, an unexpectedly satisfying dialogue between two distinct ideas of shaping space.

Tim Brinkhof

Most people think of mobiles as simple children’s toys designed to distract babies and help them fall asleep. Yet the origin of this soothing gewgaw actually marked an important turning point in the history of sculpture.

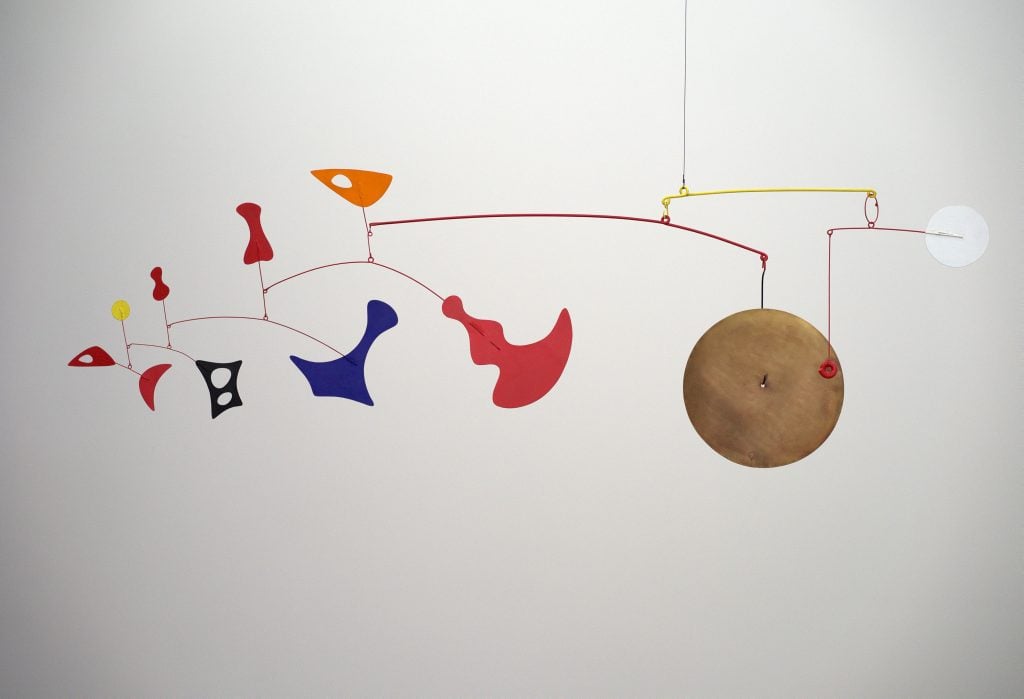

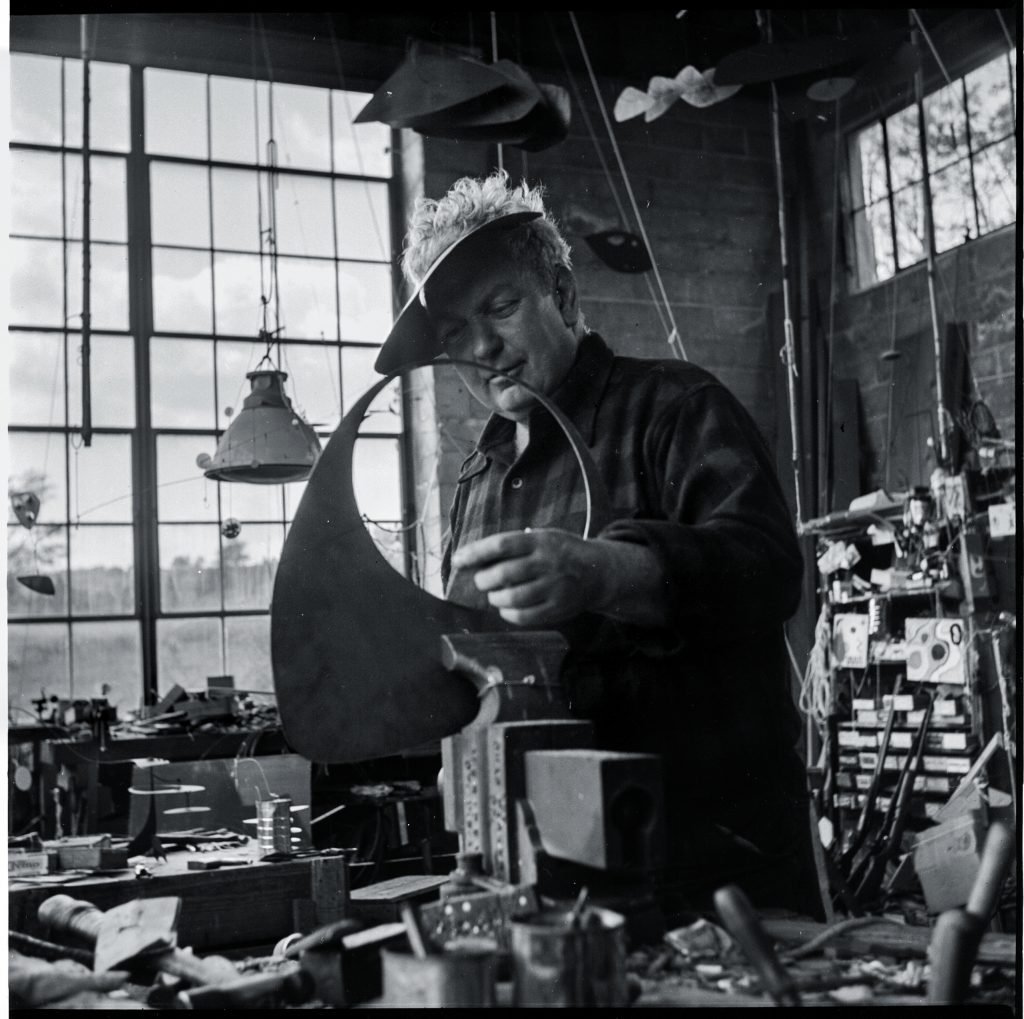

Alexander Calder first began crafting mobiles in the early 1930s, not as a commercial product to fill the shelves of toy shops, but as a means of turning sculpture from a static medium into a kinetic one, capable of defying the forces of gravity and interacting with the physical space they inhabit. (The name “mobile” doesn’t come from Calder but rather from conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp, who identified movement as their primary characteristic.)

A visionary, Calder went on to inspire scores of rebellious young sculptors eager to blow new life into this millennia-old artform. Among these was Thaddeus Mosley. The Seattle Art Museum (SAM) is exploring the connection between these two artists and their approaches to playing with movement, weight, and time in an exhibition titled “Following Space: Thaddeus Mosley & Alexander Calder,” now on view.

Alexander Calder, Dispersed Objects with Brass Gong (1948). Photo courtesy of Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York © 2024 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Calder and Mosley enjoyed radically different upbringings. Both were born in Pennsylvania, the former in 1898 and the latter a quarter century later, in 1926. Calder was the son of artists, a sculptor and a painter, while Mosley’s parents worked as a miner and a seamstress. Both artists traveled extensively in their youth, Calder with his parents and Mosley while serving in the U.S. Navy.

Struggling to be taken seriously as a sculptor, Calder was inspired by circus acrobats and how they contorted their bodies to maintain balance on trapezes and tightropes. “The idea of detached bodies floating in space seems to me the ideal source of form,” he later said of his mobiles, whose basic constructions resemble acrobatic performances.

Calder working on the pierced disc of Bougainvillier (1947) in his Roxbury studio, 1947. Photo: Herbert Matter. Photo courtesy of Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York © 2024 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Mosley took a different path. Turning to sculpture in the 1950s after working as a freelance journalist and Postal Service Employee, he was inspired by Calder. His fascination began after seeing one of Calder’s large-scale outdoor mobiles, 6 Dots Over a Mountain (1956), on a collector’s lawn.

Yet while their interests overlapped, their execution took them down separate paths. “Both artists stress a heightened awareness of forms in space and instill an anticipation of change,” Catharina Manchanda, a curator of modern and contemporary Art at the Seattle Art Museum, told Artnet. “Calder does this with his gently moving mobiles, Mosley by balancing heavy volumes that seem to defy gravity.”

In comparing the work of these two artists, “Following Space” functions as a tour of 20th and 21st century art developments, taking visitors from the foundation of modern sculpture as shaped by Calder to more contemporary 3-D work as exemplified by Mosley, who fuses Calder’s influence with other sources of inspiration, including traditional African art.

“My work, like Calder’s, has a sense of balance and imbalance,” Mosley explains in a video SAM put out along with the show. “People always say, ‘gee, it looks like they should fall over’… that’s my idea of ‘weight in space.’”

That particular concept is well-illustrated by the work that opens the show, Mosley’s Following Space (2016), one of 17 of his sculptures on display. Constructed over the course of two decades, its graceful form is reminiscent of a wave or a serpent, accentuated at SAM by the gallery’s curved wall

It finds its complement in Calder’s White Panel (1936). Considering that both these sculptures are meant to be seen from multiple vantage points, the museum has installed them in such a way that visitors will be able to view them from different floors.

Photo: Natali Wiseman.

“My hope,” Manchanda said, “is that visitors will see each of the artists in a fresh light, animated by the aesthetic contrasts: Calder’s works in this exhibition, selected in collaboration with Mosley, move delicately, whereas Mosley’s monumental sculptures rise from the ground and reach into space.”

Or, as Mosley himself says in SAM’s video, the exhibition promises to give its viewer “the idea of levitation, in two different ways.”