Art Collectors

A Famed Collection of Alexander Calder Sculptures Has Moved Into the Seattle Art Museum

A major donation by Jon and Kim Shirley, the mobiles and stabiles are currently on view in "Calder: In Motion.”

A major donation by Jon and Kim Shirley, the mobiles and stabiles are currently on view in "Calder: In Motion.”

Lee Carter

“Before Alexander Calder, no one had ever made a sculpture that was basically empty space with a few things in it,” mused the Seattle-based collector Jon Shirley. “He created a whole new art form.”

The observation is both droll and astute. The celebrated American artist of mobiles and stabiles (akin to mobiles, but static) is largely credited with giving modern art its look and feel, and shape. He did so through a careful balancing act, setting bold forms against negative space and weighing simplicity against flourish. No wonder he was called the sculptor of air.

Jon and Kim Shirley. Photo: Spike Mafford, Zocalo Studios, LLC.

Enthralled, Shirley has spent a lifetime amassing Calder objects in every medium, building one of the world’s greatest private collections of the artist’s prodigious output, spanning the 1920s to the ’70s. Now, 35 years since acquiring his first piece (Squarish, 1980), Shirley is letting go of his prized Calder collection. Earlier this year, he bequeathed all of it—nearly 50 works—to the Seattle Art Museum (SAM), where it is currently on view in “Calder: In Motion” (through August 4, 2024), housed in the museum’s double-height galleries.

Shirley—the former president and director of Microsoft, poached in 1983 from the once-mighty Radio Shack by Bill Gates himself—and his wife Kim are both trustees at SAM, where he served as chairman of the board from 2000 to 2008. (They’re also members of the Collectors Committee of the National Gallery of Art in D.C. and Tate’s International Council and North American Acquisitions Committee.)

The couple has not only donated the one-of-a-kind trove of art to SAM in a multi-year initiative, but also gifted the museum with a $10 million endowment, an additional $1 million to support the inaugural exhibition, plus an annual commitment of $250,000 to $500,000 for family programming, school visits, and scholarly research into Calder’s work, life and legacy. It’s a transformative gift befitting the titan of modern art.

The Shirley residence in Medina, Washington. Calder works (left to right): untitled gouache (1970), Moon and Waves gouache (1963), untitled gouache (1968), Squarish (1970). © 2023 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Spike Mafford/Zocalo Studios. Image courtesy of Jon and Kim Shirley.

Reclining in their spacious home, the Shirleys pointed to where their Calders once stood, or hung. “It was so enjoyable to live with them,” said Shirley. “They’re not only beautiful, but peaceful, uplifting, and mood-altering.” He surveyed the abode in the tony neighborhood of Medina, Washington—where several prominent tech tycoons have also built homes. “This room had a lot of Calders in it,” he remembered. “The main gallery had the big white Calder [Toile d’araignée, 1965], and over there was the Calder that’s now at the entrance of the show.” Kim recalled another standout. “Red Curly Tail was in the backyard,” she said, “but it was damaged from the wind so we put it in the front.”

Alexander Calder, Red Curly Tail (1970) in “Calder: In Motion,” The Shirley Family Collection, Seattle Art Museum, 2023, © 2023 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Alborz Kamalizad, Chloe Collyer.

Now, Red Curly Tail (1970) takes pride of place in the central gallery of the exhibition, along with the standing mobile Bougainvillier (1947) and the hanging mobile Gamma (1947), revolutionary in its suspension from one point, slowly rotating as it is gently nudged by the smallest air current. Other key works include Vache (ca. 1930), Little Yellow Panel (ca. 1936), Constellation with Red Knife (1943), and Dispersed Objects with Brass Gong (1948). The wooden sculpture Femme assise (1929) and Mountains (1976), a 1:5 maquette—or scale model—of one of his final commissions, greet visitors.

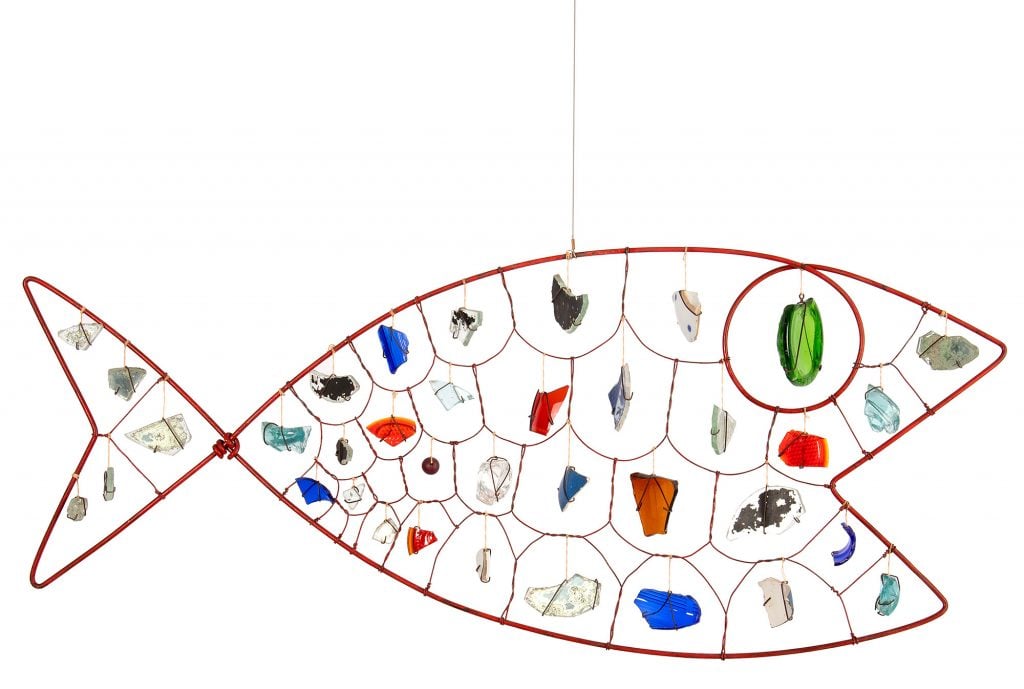

There are surprises in the show, too, works that many people might not associate with Calder, such as the painting The Yellow Disc (1958) and an untitled mobile that hung on the set of the 1969 ballet Métaboles, as well as the book Fables of Aesop: According to Sir Roger L’Estrange (1931), in which Calder drew the illustrations. In a mobile called Fish (1942), created during World War II, when metal was scarce, the artist departed from his material of choice—sheet metal—to string together assorted found objects such as porcelain and colored glass.

Alexander Calder, Fish (1942). Promised gift of Jon and Mary Shirley, © 2023 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo: Nicholas Shirley.

Shirley traces his enduring fascination with Calder back to a high school field trip in 1956. “It really hit me when we visited the Museum of Modern Art in my senior year and I went up a staircase and saw Lobster Trap and Fish Tail (1939). I thought it was amazing. Seeing that one piece hooked me on Calder.” Whenever he had the opportunity to travel to New York, he would visit MoMA, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim to see if any Calder items were on display. They often were. In 1964, MoMA held his first major survey, and in 1976, the Whitney put on “Calder’s Universe,” a sweeping retrospective featuring over 200 works, including mobiles, stabiles, and even circus figures, showcasing the full breadth of his practice.

By the late 1980s, as Shirley found success at the helm of Microsoft, his trips to New York took on new urgency; he was now collecting, and his pursuit of Calder had become personal, visceral even. “I’ve always been mechanically inclined,” he said. “I have a vintage car collection and for a long time I was very hands-on as my own mechanic. But Calder, he was hands-on, too, and he didn’t use any power tools. Everything was done with files and punches—except for the monumental pieces, which were made in a foundry according to a maquette that he had designed. That’s just phenomenal.”

Alexander Calder, The Eagle (1971). Gift of Jon and Mary Shirley, in honor of the 75th anniversary of the Seattle Art Museum, © 2023 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2000. Photo: Benjamin Benschneider.

One of those monumental pieces, and the museum’s largest Calder, The Eagle (1971) is perched outside in the Olympic Sculpture Park, a public space created and operated by SAM. One of only 16 monumental sculptures that the artist created, it was acquired in 2000 with a donation from Jon Shirley and his first wife, Mary. (Coincidentally, he first encountered The Eagle when it appeared in front of a bank building in Fort Worth, Texas, where he relocated the family for work in the early ‘70s.) Weighing six tons and standing 38 feet tall, it is, according to Shirley, the most photographed landmark in Seattle—along with the Space Needle.

Which isn’t to say Shirley has been a single-minded collector. He said that when he started, he was buying Jasper Johns, Jackson Pollock, Alberto Giacometti, Willem de Kooning, and David Smith. “Actually, I never stopped collecting other artists and I ended up with a lot of Chuck Close, too. Chuck was a friend, but the artist I wanted to collect in depth was Calder.” Now, on Kim’s recommendations, the couple collects contemporary art as well, having just returned from purchasing a Kevin Beasley sculpture.

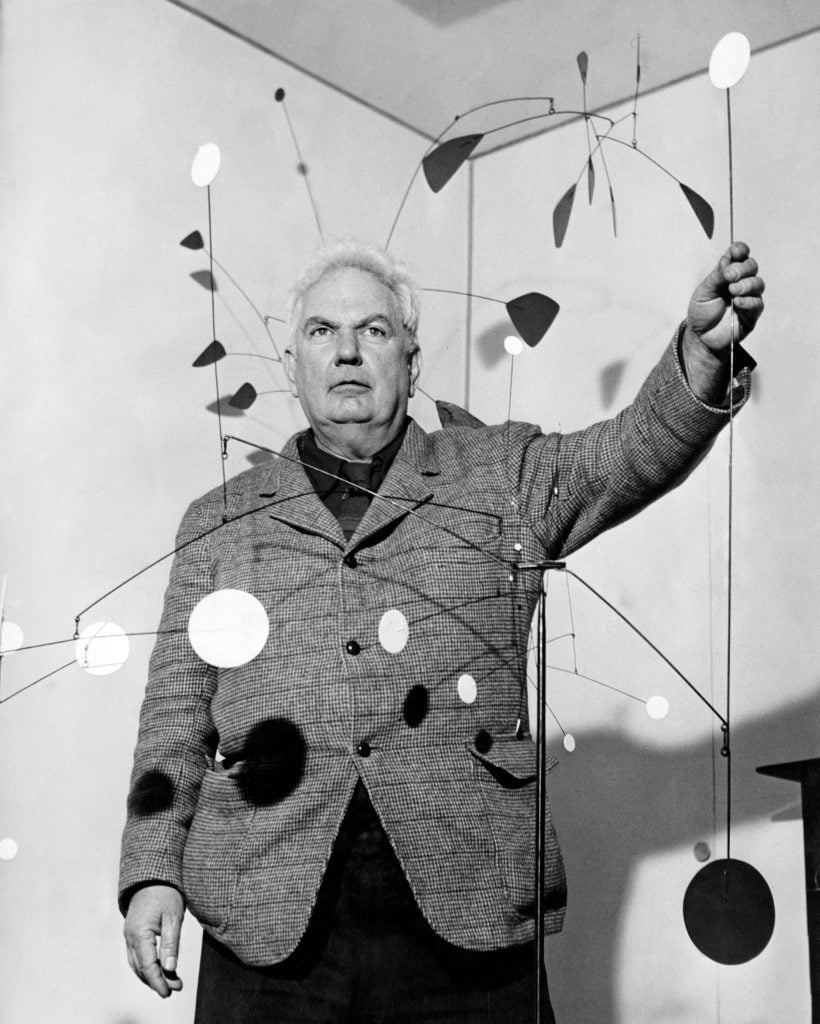

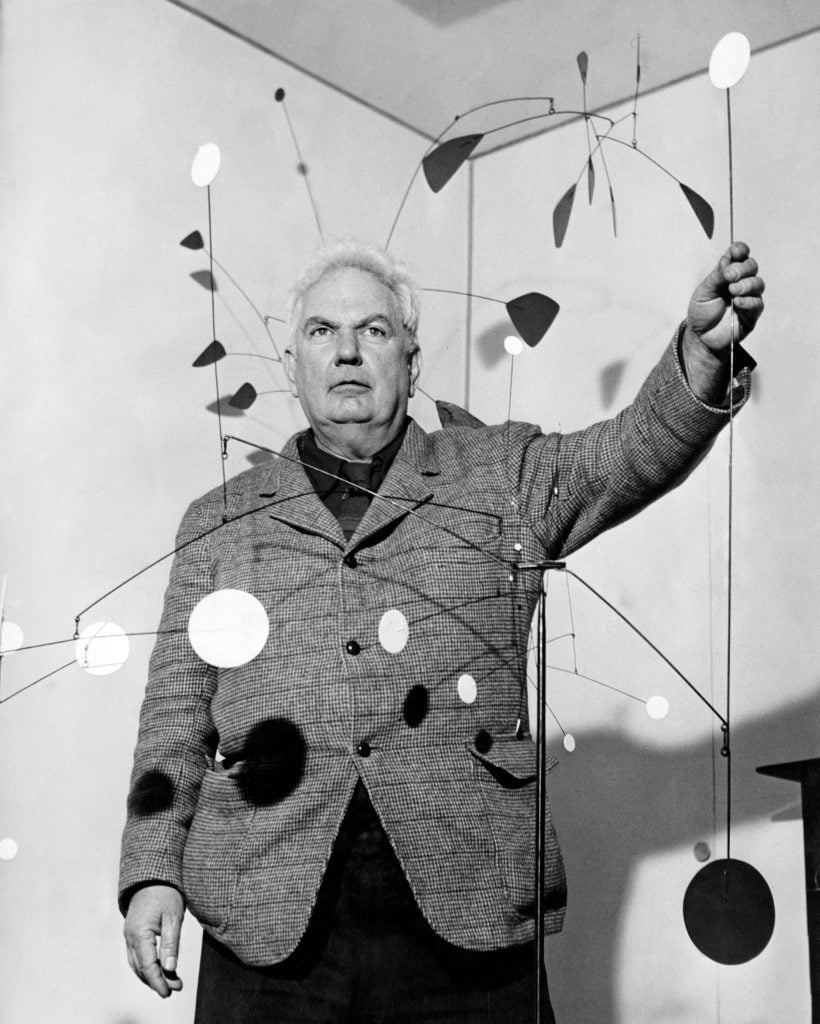

Alexander Calder with Gamma (1947) and Sword Plant (1947), Buchholz Gallery/Curt Valentin, New York, 1947. Photo courtesy of Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York, © 2023 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

While not with the Shirleys anymore, the Calder works have not ventured far from home. The collectors explained that the endowment allows for ongoing exhibitions, on which they can continue to collaborate with the museum’s curators. “We could borrow from the National Gallery,” Shirley beamed, “or the Whitney, which has a ton of Calder, or we could borrow from the Calder Foundation directly. Sandy Rower [the foundation’s president and Calder’s grandson] loves the project and told us whenever we want to do a show to just come up with a theme. So I thought of exploring Calder’s early years in Paris,” when he was involved with the Surrealists and the avant-garde.

Ultimately, it was important to keep the Alexander Calder pieces together, all at SAM. “Museums are great public institutions,” said Shirley. “For years we have lent our Calders to exhibitions in other parts of the country and around the world. It’s clear to me that museums are where they belong and we should work as hard as we can to make museums vital institutions.”