Art & Exhibitions

The Guggenheim’s Alexandra Munroe on Why ‘The Theater of the World’ Was Intended to Be Brutal

The curator explains the origins of the exhibition and the thinking behind its most controversial elements.

The curator explains the origins of the exhibition and the thinking behind its most controversial elements.

Andrew Goldstein

When it comes to the contemporary art of Asia, with all its multifaceted history and geopolitical sprawl, there are few more accomplished curators in America than Alexandra Munroe. A native New Yorker who was partly raised in Japan and studied at a monastic compound in Kyoto, Munroe became a star after organizing “Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky” for the Yokohama Museum of Art in 1994, which later traveled to the United States and did much to frame how postwar Japanese art is viewed in the country.

Now well ensconced at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum as its Samsung Senior Curator of Asian Art, Munroe is trying to repeat that feat with recent Chinese art history, working with two co-curators—the widely respected experts Hou Hanru and Phillip Tinari—to chart the arc of conceptual art in China between 1989 and 2008 in “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World.”

Now, a week before it opens to the public, the show is already proving problematic.

Intending to reflect how artists captured the violent change and bestial tumult of the two decades charted by the show—set in motion by the shattered hopes and bloodshed of Tiananmen Square and capped by the controversial Beijing Olympics, which announced both the undeniable ascent of China as a world power and its retreat from international humanitarian norms—the curators included three works that involved animals, one in which they menace each other, another in which they kill and devour each other.

The first to gain notice, a video of Peng Yu and Sun Yuan’s 2003 performance Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other in Beijing, showed restrained mastiffs trying to attack one another while chained to treadmills; another, Xu Bing’s 1994 A Case Study of Transference, featured a boar and a sow—both stamped with the artist’s trademark gibberish of fake Chinese characters, mixed with Roman letters—mating.

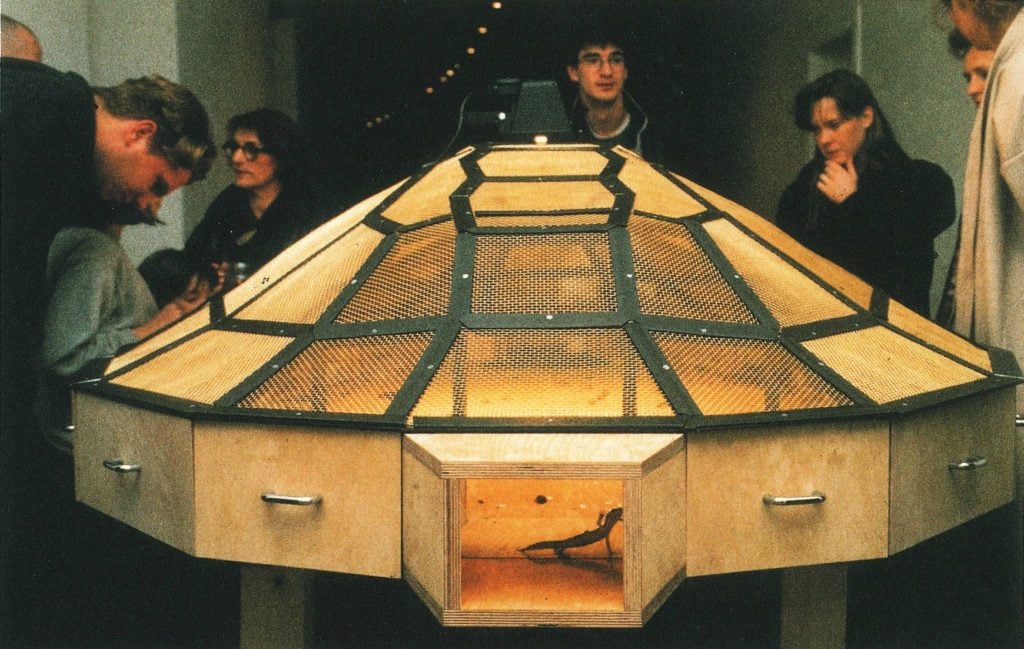

The third disputed work, and the most provocative, was the title piece: Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World from 1993, which centers on a caged arena in which insects, serpents, and lizards battle each other to the death. With its tortoise-shaped hood chillingly echoing the oculus atop Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous rotunda, the work was to set the tone for visitors entering the show.

The works swiftly met with opposition from animal rights groups, with a Change.org petition to remove the pieces—which it alleged represented “unmistakable cruelty against animals in the name of art”—gaining half a million signatures over four days. Soon, the protests grew in intensity. Last night, just after 9 p.m., the Guggenheim sent out a statement saying it would remove the pieces from the show, explaining that “[a]lthough these works have been exhibited in museums in Asia, Europe, and the United States, the Guggenheim regrets that explicit and repeated threats of violence have made our decision necessary.”

A week ago, before this firestorm began, artnet News’s editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein sat down with Alexandra Munroe to discuss the themes in her show and the artworks themselves. Here, in the first installment of a two-part interview, the curator explains the origins of the exhibition and, in detail, the thinking behind the inclusion of Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World.

Read part two of the interview, in which Munroe discusses Ai Weiwei complicated place in Chinese art history—and why Americans should learn about Chinese art for their own good.

This exhibition, which you organized together with two other heavyweight curators of Chinese art, Phillip Tinari and Hou Hanru, was clearly a massive undertaking. What set the wheels in motion on such an ambitious show?

In many ways, I’ve had this show in my mind since my first trip to China in 1991. It was among the ideas that I came to Guggenheim with. This construct of contemporary Chinese art, which had been largely imagined and promoted by the market, has not been looked at seriously for almost 20 years. The scholarship is quite vast, but very narrowly Sinocentric, and there has been very little writing about this work in an international context, relating the relevance of these artists’ work to larger issues like globalization itself. So I was interested to tackle this problem, and I presented it to Richard Armstrong as early as 2014, right as “Gutai: Splendid Playground” was coming to a close.

We launched the Chinese Art Initiative [with the Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation] in 2014, and that also came directly out of my intense curiosity to know more about this area, as well as out of an increasing frustration I felt looking at what appeared to be a very contested field.

How did you come to work with Hou Hanru and Phil Tinari?

I knew immediately that this show was too big for one person. Hou Hanru had been a founding member of the Asian Art Council, and I had begun to speak a lot to Phil Tinari on all of my trips and really liked his thinking, his writing, and his approach. He has a very healthy skepticism of the project of China, and also about this construct called contemporary Chinese art. What the hell does it mean? Who is deciding what it means? Can we go actually back to the artists and the individual artworks and break out of this national construct?

So the partnership evolved quite naturally. And while I’m the lead curator, we are testing each other’s ideas, and we are bringing works of art that no one of us would do if it were a single-curator show. It’s a signal to the world that this is not a canonical declaration, it’s a set of positions. We’re not saying this is the new textbook—we’re saying this a new way of asking questions about some of the fundamental ideas that face us when we look at the phenomenon of Chinese artists during this period.

The last time New Yorkers saw a major exhibition of Chinese contemporary art was the “Inside Out” show at the Asia Society, which took place 10 years before your cutoff date of 2008. How does your show advance the narrative of Chinese contemporary art as it has evolved since then, and what is it that makes this show a fresh reading of the subject?

What’s very different, from our perspective, is that this is a historical contemporary show. We are very deliberately bracketing this between 1989 and 2008. Because of the success of “Inside Out” and other shows, and because of the enormous contributions of scholars like Wu Hung, who published extremely important foundational texts in English on this period, we can now take a different tack. So it’s not encyclopedic—it’s not even a survey. This show is about a movement of two generations of Chinese conceptual artists, working all around the world with an awareness of being a global citizen, and full of questions about that status.

We are also looking at this from the vantage of the Guggenheim Museum—an international museum—and not the Asia Society. And we are landing on a strain of this material that is conceptual, and placing it within the context of global conceptualism. People have asked me, “Why aren’t you sending this show to China?” This isn’t made for China. This show is made for an American audience. I’m really pleased that it’s going to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art because I think it’s going to have a different set of meanings and resonances on the West Coast, because the West Coast has its history with China, including many Chinese artists in its population.

A big part of the intended audience [for us] is artists here. If a show does not touch artists here—if artists aren’t talking about your show—forget about it, it sunk. Our number-one goal with this show is for artists to be excited, and moved, and for their eyes to open up to what their counterparts have been thinking about during this period of globalization that we all share. The stakes are quite different for these artists than artists living here. I think we have a lot to learn.

You make a compelling argument for why you set your show between 1989—the year of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the birth of the Web, and the horror of Tiananmen Square—and 2008, with the Beijing Olympics and the financial collapse. But why is now, 2017, the right time to do this show?

Well, of course, the timing was completely driven by the Guggenheim calendar, and this was the opening and we took it. But I think curators, like journalists, have antennae, right? We understand when there is a right time to do a show and when it’s going to have resonance.

I don’t think I could have anticipated the political climate in this country now, and I don’t think I could have anticipated the situation in China today, and how critical it is for Americans to have a better understanding of China as a global presence. So sometimes this confluence can be quite accidental.

When it comes to the artists in your show, there are some who are already famous here, in large part due to “Inside Out,” and some who will be bracing new discoveries. In the show’s catalog you mention that when you told artist Wang Jianwei about your plans for the exhibition, he said, “Let the wild animals out of the zoo—let them roam.” What did he mean by that?

Wang Jianwei was one of the first artists I approached about this exhibition, when I was kind of testing the waters. And he said, “Why would you want to do this show?” And I said, “You know, I feel like these artists have been living in a zoo, and the zoo is China.” And he said, then, to let them out of their cages.

“Cages” is a good segue to the artwork that gives the show its title. Theater of the World is an installation from 1993 that may have a major impact on American audiences, a caged-in setting featuring live animals that evokes the philosopher Thomas Hobbes’s description of life in the wild as “nasty, brutish, and short.” There are scorpions, snakes, spiders, lizards, toads, and large bugs, fighting and sometimes devouring each other. Can you tell me a little bit about this artwork, and what role it plays in the show?

Well, I will give Hanru credit for landing on that as a great title for the show. In my history with exhibitions, the title usually comes last, but in this case the title has stuck for three years. It was just right from the start.

I had begun to study this piece around 2009, when we were acquiring a group of works for the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi from the collection of Guy and Mimi Ullens. That extremely important collection of Chinese art, which was the largest in the world in private hands, has since been auctioned off in pieces. But we knew Mr. Ullens, so he approached us to ask if we would be interested in looking at this material first.

I spent close to two years researching which objects we would like to acquire from thousands of works, and one of the works we acquired was Theater of the World, which is actually a two-part installation composed of Theater of the World and The Bridge. The Bridge is this serpentine, cage-like structure that is 30 meters long and that arches over a tortoise-like cage structure that rests beneath it, which is Theater of the World.

Huang Yong Ping created this installation for Stuttgart’s Akademie Schloss Solitude when he was a resident there in 1993. He had left China in 1989—he was one of the first Chinese artists to permanently emigrate and become a French citizen.

So he was already thinking about the nature of identity, about how the internet had already become an early motor of globalization in the world, and how a newly borderless world was announcing the end of contemporary art as we knew it, as the sole purview of Europe and America. He was interested in chaos, he was interested in how different species combat each other and also coexist, and he was interested in inserting a radically different philosophical notion of how the world works into a very Enlightenment idea of progress. So this work draws on many sources, and it is exactly that multiplicity of sources that makes Huang Yong Ping the perfect artist to open our show.

Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World. Photo courtesy of the Guggenheim.

Can you talk a little more about the ideas in the piece?

“Theater of the World” itself is the name Huang Yong Ping appropriated from the panopticon, which was what the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham called the design he came up with in the late 1700s as an architectural model of surveillance for a prison or an insane asylum, with a surveyor stationed in a central tower to watch the behavior of the inmates who were ringed all around him, every movement visible. Then in the 1960s, Michel Foucault takes that panopticon model as a metaphor for the controlling mechanisms of modernism that leads to the structures of colonialism, imperialism, and all hegemonic systems of power.

Huang Yong Ping, who educated himself instinctually and had read an enormous amount of material on postmodernism available to the Chinese avant-garde from the mid-1980s onward, read Foucault and understood that the basic project of the early 1990s was to kind of complicate the project of modernism. His project, not only with this work but with all his work, is to question systems and dominating ideologies, including the West but also including China, Communism, and neoliberalism as it was gaining force in the early 1990s.

We wanted to open the show with this work because, number one, it’s big—the only place it could fit was the high gallery. But more than that, it introduces the visitor to a kind of visceral realism that is evident in so much of the most important work in this show. It introduces the visitor to an artist’s thinking that is embracing chaos, that is filled with questioning, that is atheistic, that is fearless of any governing ideologies, that is asking tough questions, and that is brutal. If you can’t survive the high gallery, don’t bother seeing the rest of the show. The work in the show is intense.

Why does it have to be so brutal?

It’s gritty and tough and brutal because that is the world these artists have lived in. They are not just witnesses—they are the agents of so much change that happened so fast and with such mighty force all around them from the ’60s and ’70s to the 2000s that no single individual could possibly have any control over it. It was like a maelstrom. These artists are asking themselves what is it to be an individual, how they can reclaim their bodies, their minds, against this tide, where we can believe in nothing. Huang Yong Ping’s answer is that we can believe in reality. Reality is the first and last resort.

It will be interesting to see how this piece is received, since it may speak to a stark difference in sensitivities between China and the United States. In China, there’s a tremendous amount of sensitivity around anything that makes an overt political stand against the government, or, especially, anything that has to do with Tiananmen Square—even including the date of June 4, 1989, on an artwork is a radical gesture. Here, in the United States, political stances in museums are par for the course, even expected. But animals are the third rail—even the slightest hint of an animal being mistreated or discomforted can create a firestorm.

We’re prepared.

What kind of reception has this piece had in the various places it’s been exhibited over time?

Tough. In Vancouver, the museum ended up shutting it down because the public outcry was rather intense. We are taking every precaution to avert that. We are working with a top animal-care handler who works with many museums that have included animals in shows, as many museums do. There are parrots in Hélio Oiticica’s show right now downtown at the Whitney. We had thousands of ants in Anika Yi’s recent installation.

A lot of artists work with animals, and they have for a long time. We are privileged to be in New York City, where we have the best of the best animal handlers. But these animals [in Theater of the World] were bred for pet consumption, and they are used to living in somewhat artificial environments.

In our case, we’re taking every precaution to give them full-spectrum light, and we have the handler coming in to feed and take care of the animals in exactly the way they need to be cared for. And the food they are being given is their natural food. There might be some other interesting interactions going on in there, which the artist wants, but we’ve also noticed in other iterations that certain species that don’t naturally coexist end up sort of hanging out together and protecting each other.

What the artist is asking us to consider is the globe itself—“The Theater of the World”—where we’re all different species vying for dominance and it’s a contest. But it’s also a symbiosis, because we’re all on this planet together.

Another very important point for Huang Yong Ping is the Chinese term for “poison,” because the character is actually composed of many radicals and those radicals stand for an earthenware jar in which five venomous animals are placed alive. The top is shut, and then a year later some Daoist sage opens the jar and the animal that has survived the longest is considered the devourer of power. Because that animal has digested the venomous power of all the other four species, its stomach is considered the elixir of life.

Whoa.

So Huang Yong Ping sees the animals in his piece as not only eating each other, but also nourishing each other.

Well, you know, Americans don’t like to think that their hamburgers come from anything other than a supermarket.

Yeah. What do you think your beloved dog eats?

What reaction do you anticipate?

We will see. It’s quite fascinating. We’ll see what the reaction is. I think we’re well prepared, but I think we also want to remind people that this is both a metaphor and it’s real. That they will digest this, be nourished by this, and they will move on.