People

‘Most Rock Guys Do Art When They Don’t Tour’: Alice Cooper on Collecting Warhol, Collaborating With Dalí, and His Own Budding Painting Practice

Cooper says Surrealist art inspired his legendary shock-rock act.

Cooper says Surrealist art inspired his legendary shock-rock act.

Osman Can Yerebakan

Rumor has it that Andy Warhol first got the idea to depict electric chairs as part of his iconic “Death and Disaster” series after seeing a rock show where Alice Cooper performed on-stage stunts with a prop electric chair. In the 1970s, when both artists were at the peaks of their careers, they became passing friends in the gilded corners of New York’s nightlife landmarks, like Max’s Kansas City, where they rubbed shoulders and partied together, along with the rest of the Factory entourage.

Given the Pop art master’s fascination with death and plasticity, the urban legend might well be true—and the interest was mutual. In 1971, Cooper has said, a model ex-girlfriend bought him one of Warhol’s “Electric Chair” prints, which the artist first made in 1963 by appropriating a press image of the device used to execute Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for espionage.

This past weekend, just off a 26-venue fall tour, Cooper put the screen print, Little Electric Chair (Red) (1964-65), up for auction, where it was expected to fetch $2.5 million to $4.5 million at Larsen Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona (the state Cooper has called home for decades).

The work was authenticated by Warhol expert Richard Polsky, but rumors about its authenticity have persisted and the print ultimately failed to sell. (Polsky’s website names the “Little Electric Chair” series as among the most forged by the artist, along with his “Flower” paintings and “Marilyn” prints.) Cooper plans to offer the work through a private sale in the future.

We caught up with Cooper while he was on tour in Mississippi to chat about the Warhol, the ways Surrealism inspired his legendary stage act, and his own burgeoning painting practice.

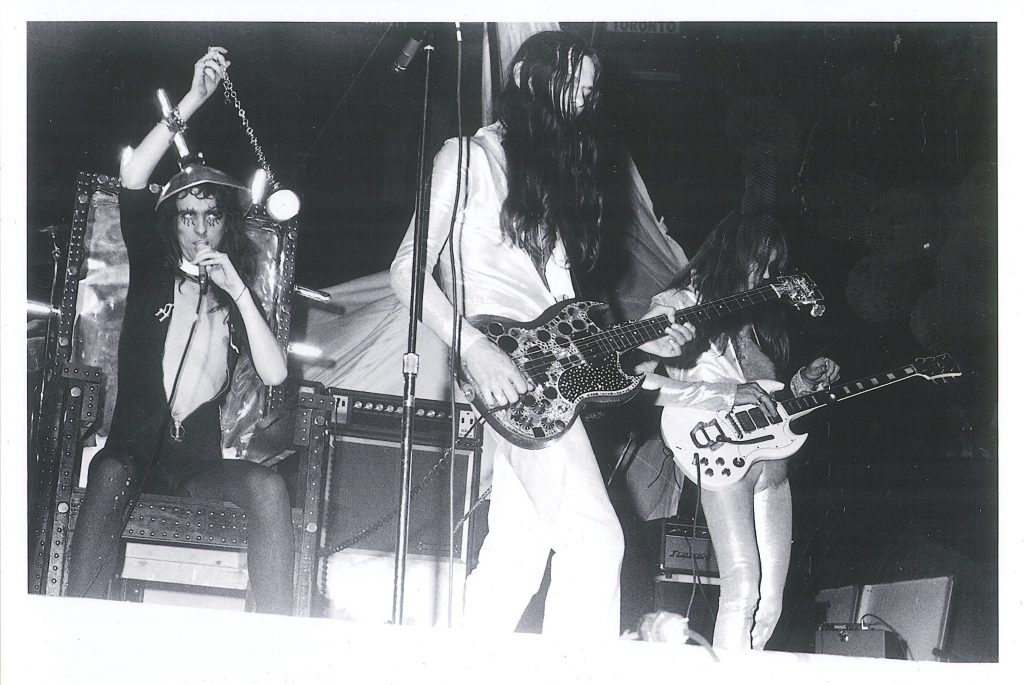

Alice Cooper performing with an electric chair.

What was your initial reaction to the “Electric Chair” series? Did you need to be sold on the idea of buying an edition or was it love at first sight?

Back in 1970s, the band was known for using all kinds of props on stage, like guillotines, snakes, and, in fact, electric chairs. My then-girlfriend Cindy Lang thought Warhol’s electric chair silkscreen would be a perfect birthday gift and she bought it for $2,200. She used to work with Interview magazine and was somewhat involved with the Factory circuit, and I think she loaned the sum. I loved it and we hung it in our living room in Los Angeles.

I hear that it was the late actor Dennis Hopper who first told you how much Warhols go for these days?

Dennis was a good friend and a golf partner. My daughter and I were sitting with him at the Kentucky Derby in either 2008 or 2009. He had just sold one of his Warhols for $7 million. Three beats later, I remembered I had one too! I called my mother, who was then staying with us in Arizona, to check it out in our garage—and it was there, after sitting rolled up in a tube for 30 years. Arizona summers see 150 degrees, so everywhere is always air conditioned—luckily the garage is too.

Were you involved with the art world back then? It seems like the music and art scenes were more incestuous in 1970s and the ‘80s.

When Cindy bought the silkscreen I was familiar with Warhol and had partied with his crew a few times. He was upfront about everything, including how anything could be art. This was a unique, in-your-face idea. Rock musicians and artists all hung out in the same circles and places, like Max’s Kansas City and Studio 54. The avant-garde always found each other, whether in music or art. I have an art major and always considered my stage show and persona an artistic extension of my music. This was around the time I collaborated with Salvador Dalí for his hologram, First Cylindric Chromo-Hologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain (1973).

Chris Loomis / © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Was the Warhol the first artwork you collected?

I had a few Larry Rivers paintings before—I also knew him from the same circle. Then I started collecting a lot of artists from Arizona, where I live. I am a fan of the artist Guzwa. I have eight of his paintings of dated Route 66 motels with 1950s neon signs. Another local artist I collect is Anne Coe, who makes work about Americana—lizards or rockets—all with a sense of humor.

I have a feeling that you would also like Warhol’s “Car Crash” prints.

True, because it’s all about destruction [laughs]. The experts who inspected my red electric chair agreed that it a rare one for having the word “silence” printed visibly and legibly. In other colors, the word is apparently faint.

How different was the art scene then compared to today?

It feels like every musician or actor is an artist today—I’ve just heard that Gene Simmons makes art. There are eight paintings I’ve done out there. I gave them all away so I couldn’t tell you who owns them now. When I started the band with my bass guitarist Dennis Dunaway in 1960s, we both came from studying art and our intention was to do something similar to the Surrealists on stage.

Tell us about your own studio practice. Did it start and evolve parallel to the music?

I started with making intricate drawings with pen and ink, which was quite time consuming. Later, I got into acrylic—it’s easier to work with than oil painting, but oil’s impact is beyond other paints. I’ve realized most rock guys do art when they don’t tour. Since we couldn’t tour since last March, I had to do something with the urge and started painting again. I am making contour drawings, which is a new territory; some of them are abstract landscapes. There is always some dark humor, though. For example, a drawing of a cute bunny in a guillotine. Art needs a sense of humor.

You seem to be more engaged with painting than ever. Will you continue, and maybe show with an Arizona gallery?

I’ve made around 20 paintings so far and will definitely continue. Maybe around eight of them are worth exhibiting so I need another year or so for a show. What peaks my interest about painting is that I don’t have to answer to anybody; there’re no boundaries and they speak for themselves. The trick is to know where to stop. I am a believer of the expression, “If everything is screaming, then nothing is screaming.” I compare painting to songwriting—in both, you start not knowing where the path will take you and it never ends up the way you envision. The paintings are getting larger in scale so, yes. I turned one of the large rooms in the house into a studio—even the recoding room is smaller.