Art World

An ArtPrize Surprise Lights the Way to a Better Art World

Anila Quayyum Agha's double-win marks a first for the populist ArtPrize.

Anila Quayyum Agha's double-win marks a first for the populist ArtPrize.

Cait Munro

On October 10, after almost three weeks of art, celebration, and critical discourse that temporarily transformed the otherwise sleepy, conservative city of Grand Rapids, Michigan into a veritable cultural hot spot, the winners of the sixth annual ArtPrize competition were announced. The fanfare surrounding the proclamation mimicked that of years before (an Academy Awards-style ceremony, a parade through town, copious after-parties), but something about this iteration was different. Different not just from prizes past, but from art exhibitions on the whole.

The critics and the masses, for once, agreed.

Indianapolis artist Anila Quayyum Agha took home the Popular Vote Grand Prize and split the Juried Grand Prize with another artist, Sonya Clark. These two wins, combined, resulted in a jaw-dropping, life-changing $300,000. It is the first time in ArtPrize history that the two grand prizes, each representing a different side of the art-appreciation spectrum, have been awarded to the same artist.

In fact, it was a year of firsts. Coincidentally, it was the first time since the Juried Grand Prize’s 2012 inception that the two prizes have been equal, each worth $200,000 (except, of course, in an event like this year’s tie). It’s one of the first times the art world elite hasn’t lambasted, or perhaps worse, dismissed the Popular Vote Grand Prize award winner. That is probably because it’s also one of the first times the chosen artwork has been in sync with the overarching aesthetic tastes of those “in the know” about art.

By choosing to level the prize money between the “popular vote” and the “critics’ pick,” ArtPrize exposed itself to criticism that the award was abandoning its roots and becoming too elitist. Alexandra Peers, in an essay for artnet News, wrote “ArtPrize is the only event of its kind in the world, and that uniqueness is far more interesting than any emerging star that could rise out of it, even one picked thoughtfully and with all good intent by perceptive art world jurors.” It’s an important point, but when the beloved idiosyncrasies somehow magically coalesce with the thoughtful opinions of the jurors, perhaps the emerging star actually already has eclipsed the competition that birthed her.

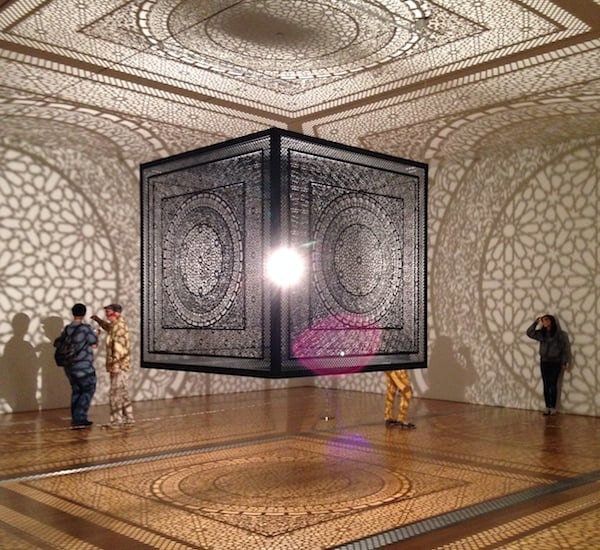

Anila Quayyum Agha, Intersections (2014) at ArtPrize.

Photo: Cait Munro.

Agha’s winning work, Intersections, is deceptively simple in its materials—a suspended, six-foot wooden cube with intricate laser cut-outs and a single light bulb inside. To attempt to describe it is to do it an injustice. But upon entering the room in the Grand Rapids Art Museum that housed the installation, its sweeping appeal is immediately evident. It is delicate, experiential, and enveloping. Chatter is reduced to an awestruck hush. Visitors stare, captivated and a bit overwhelmed, before inserting themselves into the space, which ultimately welcomes them. The constantly shifting shadows provide a personal, interactive experience for every visitor. It is, as the artist says, “a private experience in a public place…[one] that will make you feel above yourself.”

While enchanting and joyful, the work is not without deeper meaning, which is an important box to check for critics unlikely to bestow a six-figure award on something that’s merely fun to look at. Drawing on her experience growing up in Pakistan, Agha created the space as a response to the exclusion of women from mosques. The geometric patterns are reminiscent of Islamic sacred spaces, as is the spiritual feeling the room somehow automatically takes on. But by removing overt religious context, the artist has reclaimed a space she was once rejected from.

Perhaps in its sixth year, ArtPrize visitors have become more savvy about contemporary art, choosing to select a thoughtful installation over a quilt or a painting of the Crucifixion (the winners of previous years). But maybe this cross-over success just gets at a universal truth about what we (from the uninitiated to the experts) want from art: a degree of spectacle, something that’s going to force us to pay attention (especially after a day, or a lifetime, of viewing art), but nothing too ostentatious (like a massive, shiny balloon dog, for instance), something that appears to have taken skill to create (not something that “my kid could have made”), and finally, something beautiful. No matter how much one enjoys or appreciates challenging pieces, it’s impossible not to be floored in the presence of this kind of sheer beauty.

In a post-announcement interview, I asked Agha what it felt like to have made something so engaging to such a wide variety of people. “My intent was to create a sacred space where everyone is equal and no one is left out,” she responded. While the statement applies to the initial act of building a non-discriminatory spiritual place after years of facing discrimination, it works in a larger sense as well. Matters of location, religion, education, political affiliation, and socio-economic class may matter less than we think, at least in terms of what reaches us at our core. Maybe we should be tougher on our art, and ask that no one be left out. Sure, some work is far easier to understand with an art history degree, and some work is far easier to appreciate without one, and that’s okay. But we need more art that allows for both, but requires neither.