Archaeology & History

New Study Finds Ancient Egyptian Scribes Suffered Back Pain Just Like Us

Joint issues were caused by hours spent bent over papyrus.

Desk jobs can take a surprising physical toll on the body. White collar workers complain of stiff necks, sore lower backs and aching joints. It may bring them little relief to find they continue a millennia-old tradition of work-related pain. According to a new study published in Scientific Reports, scribes were suffering with similar issues back in the days of the pyramids.

A team of archaeologists examined dozens of adult males’ skeletons from the necropolis at Abusir, Egypt, which was used between 2700 and 2180 B.C.E. Written evidence indicates that 30 of the studied males lived as scribes. These high ranking dignitaries enjoyed privileged lives with an elevated social status thanks to their literacy, at a time when only one percent of ancient Egypt could read and write.

Records indicate that influential families sent their sons to the royal court for education and training. Eventually, they became scribes who served a similar societal role to contemporary government workers. “These people belonged to the elite of the time and formed the backbone of the state administration,” explained Veronika Dulíková, an Egyptologist and member of the archaeology team. “Literate people worked in important government offices such as the treasury (today’s Ministry of Finance), the granary (today’s Ministry of Agriculture). They also played an important role in the collection of taxes, in temple cults and in royal pyramid complexes.”

While Egyptian scribes’ lives have been studied in detail, their archaeological remains have never before been examined for anomalies. The study’s lead author, Petra Brukner Havelková, is an anthropologist at the National Museum in Prague who has specialized in identifying activity-induced bone markers for nearly two decades.

When comparing the remains of scribes to non-scribes, the former were found to suffer from osteoarthritis, a breakdown of the joint tissue. The condition was found in joints connecting the lower jaw to the skull, the right collarbone, the upper right arm bone connected to the shoulder, the bottom of the thigh, right thumb bones, and throughout the spine.

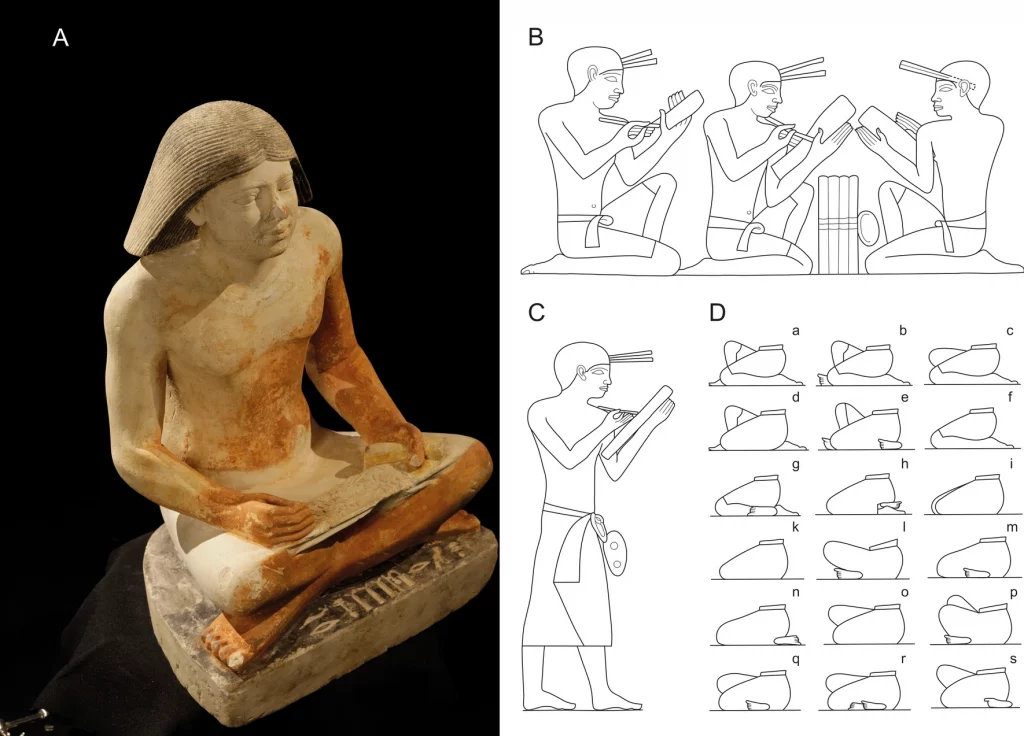

Working positions of scribes. Drawing Jolana Malátková

Just as modern-day government workers suffer neck and spinal injuries from sitting at desks and arching forward to stare at screens, ancient Egyptian scribes endured comparable physical stresses from hunching over papyrus for prolonged sessions.

It is theorized that scribes often squatted on their right legs, which may explain why significant damage was found on the skeleton’s right sides, with particular degeneration in their right knees.

Historical sculptures, such as The Seated Scribe, corroborate that scribes frequently knelt or sat cross-legged while writing. They recorded their notes on sheets of papyrus, pottery notepads called ostraca, or wooden boards. Scribes generally wrote in hieratic cursive, a simpler script more practical for everyday note-taking, rather than using the elaborate hieroglyphs carved on monuments by specialists.

Researchers were most surprised to discover damage in the scribes’ jaws, which is explained as a consequence of chewing on rush stems to make brush-like heads. They used these rush pens, and later reed pens, to write their notes, pinching the utensils between the index and thumb fingers of their right hands.

Looking to the future, the study’s scientists are seeking to collaborate with other research groups to analyze scribes’ remains across other ancient Egyptian cemeteries.