Archaeology & History

Ancient Lipstick Dating Back More Than Three Millennia Is Found in Iran

The pigment could be among the world's oldest cosmetics.

This Valentine’s Day, get your honey a vial of ground hematite. A container of red lipstick from the Bronze Age was discovered in Iran, according to a new study published this month in the journal Scientific Reports by teams from Tehran and Italy.

The small vial is among a trove of artifacts first discovered in 2001, when the Halil river in the Kerman province in southeastern Iran flooded several graveyards from more than 5,000 years ago. The flooding led to items from the burial sites surfacing.

The object would end up in the collection of the Archaeological Museum of Jiroft, though its precise provenance remains unknown. The vial and its contents are dated to some point between 1936–1687 B.C.E., what the team called a “relatively early date” but “far from surprising, considering the long-standing, well-known technical and aesthetic tradition in cosmetology in ancient Iran.”

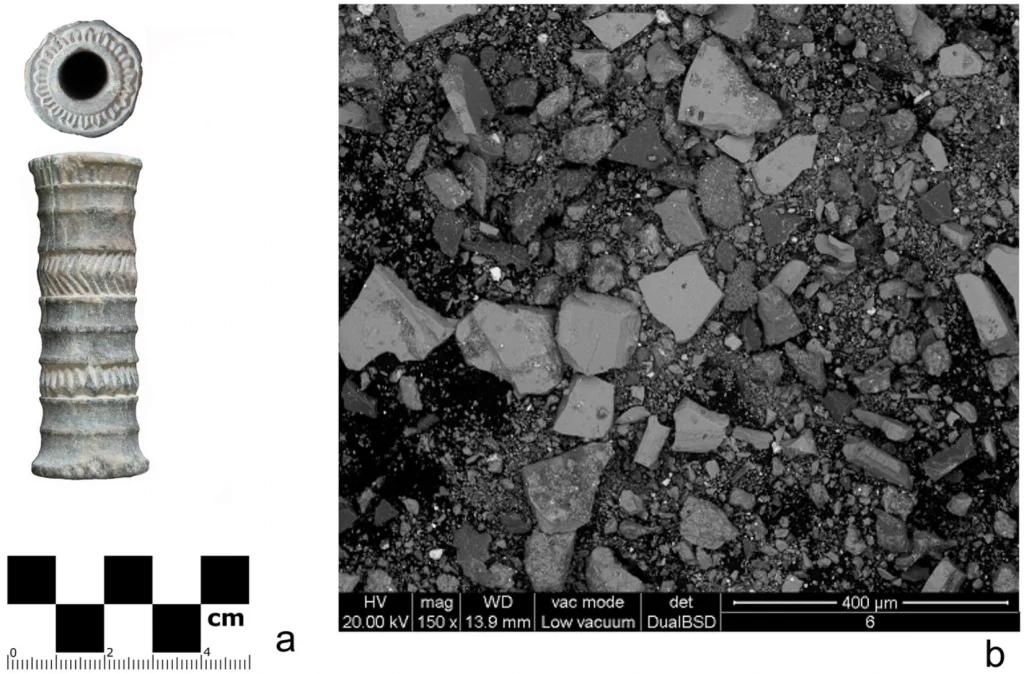

The container is made of greenish chlorite and bears intricate craftsmanship with “fine incisions,” according to the study. Researchers characterized its specific size and “slender” shape as “distinct and unlike any other similar object currently known,” indicating that cosmetics were likely branded and packaged in a similar way they are marketed today.

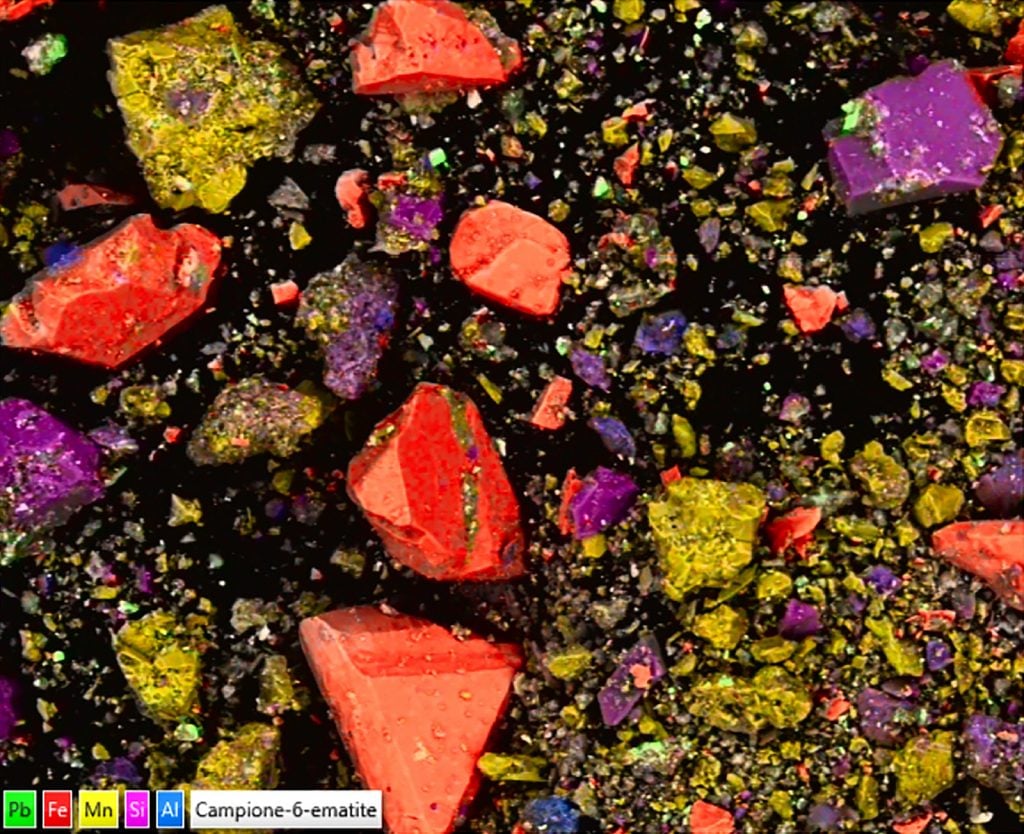

A vial of Bronze Age lipstick is seen left, with a microscopic view of its contents right. Photo: M. Vidale, F. Zorzi.

The team theorized that the shape and thickness of the vial also suggest it could have been conveniently held in one hand with a copper or bronze mirror, “leaving the other hand free to use a brush or another kind of applicator.” This is supported by a fragment from the Turin Papyrus 55001 found at Deir el-Medina in Egypt, showing a young woman painting her lips and holding such a vial.

“What was left of the contents was effortlessly extracted in the form of a loose, dark purple fine powder,” the study authors said. “Soil burial contamination, in principle, cannot be excluded but in the light of subsequent observation at the optical microscope it looks minimal.”

The team used a variety of technologies to analyze and date the pigments, discovering mineral components including ground hematite, quartz, braunite, anglesite, and rare tiny crystals of galena—a lead mineral. “The respective amounts of lead minerals are very limited,” the researchers wrote, adding that the minerals that produce a deep red—primarily hematite—make up more than 80 percent of the analyzed sample.

The powder also contained some vegetal fibers, which the researchers suggested were possibly used to make the lipstick fragrant. “Ultimately, the deep red cosmetic is compatible with a lips coloring preparation—probably the earliest so far analytically reported,” the researchers said.

The researchers noted that it remains unknown precisely the agency, gender, or sex-specific identities of anyone buried in the graveyards in the region and, as such, impossible to precisely conclude who might have used the lipstick and under what conditions.

“In case this and other cosmetic substances, in certain periods and in certain contexts, should turn out to be consistently associated to female burials, one could explore the possibility that this gradually enhanced technology was also a function of increasing social stress to which women were exposed in times of fast social change,” the researchers concluded.