Art & Exhibitions

What Andrea Rosen Wants You to Know About Felix Gonzalez-Torres

His close friend speaks from the heart.

His close friend speaks from the heart.

Rain Embuscado

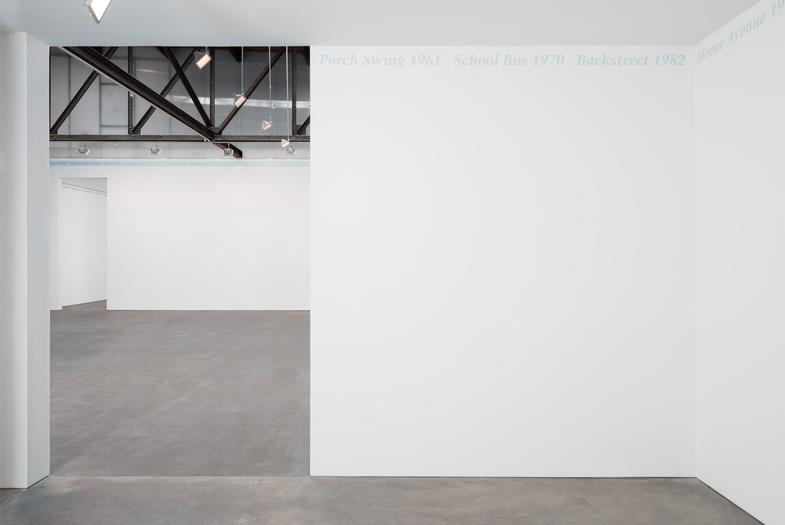

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Beginning), 1994. Installation view, Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York NY, 1997. © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation. Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

On the occasion of Felix Gonzalez-Torres‘s simultaneous, three-exhibition extravaganza in New York, London, and Milan, artnet News arranged a phone interview with his friend and art dealer Andrea Rosen.

Rosen has been managing his career (and, later, his estate) for over twenty-five years; and in the case of an artist whose conceptual offerings mystify most, she bears the unique challenge of keeping her friend’s ineffable vision alive.

“Every time I speak about his work, there’s the opportunity to nuance ideas,” Rosen explained, adding that conveying the openness in his practice is particularly difficult. This dilemma, ultimately, prompted her to withhold descriptions about the works in his summer shows altogether.

Rosen’s cautious posture is evidence of her unwavering commitment to the artist’s legacy. The decision to omit textual companions reflects Gonzalez-Torres’s own aversion to imposing narratives.

“All of his works are untitled,” she noted, “All of these narratives are outside of the quotations marks. There is no fact; there is no description. Everyone who loves Felix is about keeping the work open.”

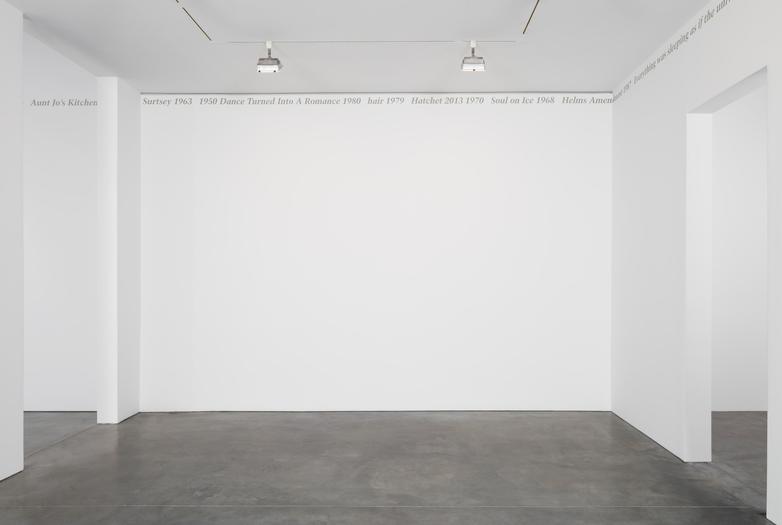

Installation view. ©The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

In the spirit of this cause, artnet News rounded up the highlights from the hour-long interview.

Gonzalez-Torres believed that equality was of utmost importance.

According to Rosen, Gonzalez-Torres strove to achieve a connection with every person in his audience. “The most powerful thing he could do was create a sense of equality,” she said. “The most political thing for him was to create equality and to operate in the center.”

Because from this position, he was open to everyone seeing the work.

“Felix had a show at the Hirschhorn in 1994. It was the height of Jesse Helms,” Rosen recalled. The work on view at the museum, “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers), showed two synchronized clocks beside each other, signifying the relationship between the artist and his lover, Ross Laycock. At the time, Helms was the senator who had recently launched a homophobic campaign to cut national funding for controversial artists.

“Felix was excited about the idea that he was going to go to his exhibition and try to close it down,” Rosen continued. “He said, ‘He’s going to go in and he’s going to see those clocks on the wall, and he’s going to think about himself and his wife. That is completely and utterly an appropriate response to this work.'”

Installation view. ©The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

The artist’s approach was prismatic.

“Felix never talked about a piece from any specific kind of view,” Rosen said. “He would call me six times in a day and talk about a work from six different angles and stories. There is no one reading. The more profound, or the broader your ability to perceive, the more responsible and complex the work would be.”

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Wawannaisa), 1991. (c) The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation. Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York. Photograph by Lance Brewer.

Instead, he focused on capturing what was most essential.

“His work allows this opportunity to feel deeply. Our obsession with things that are concrete is in some way greatly lesser than something that has the malleability to transform itself through time. That’s one of the most amazing things about his work: Because of its ability to shift and change, it continues to have the original impact. He was always asking, ‘how do you get to the core of what is meaningful?'”

The artist believed that change was the only constant.

“One of the things Felix said most often is that ‘the only thing that’s permanent is change. At the core of Felix’s work is this innate idea that because something existed, it will always exist. The rigor in his work is inspiring these people through a profound emotional connection to actually let down their guard around fear, and confront it.”

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s three-part exhibition is at Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York until June 18; Massimo De Carlo, Milan until July 20; and Hauser & Wirth, London until July 30.