Law & Politics

How Pricey Is Warhol? A Dealer Now Wants $250,000 for One of the Pop Artist’s Cardboard Boxes

Art dealer Heather Sacre says that a cardboard box that housed a set of Warhol Marilyns is worth a quarter-million dollars.

Art dealer Heather Sacre says that a cardboard box that housed a set of Warhol Marilyns is worth a quarter-million dollars.

Brian Boucher

What’s a cardboard box worth? A quarter of a million dollars if it houses a rare set of Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe screenprints—at least according to one art dealer. Just such a cardboard box is at the center of a $250,000 lawsuit that’s pitting a Wyoming gallery against a venerable art shipping company.

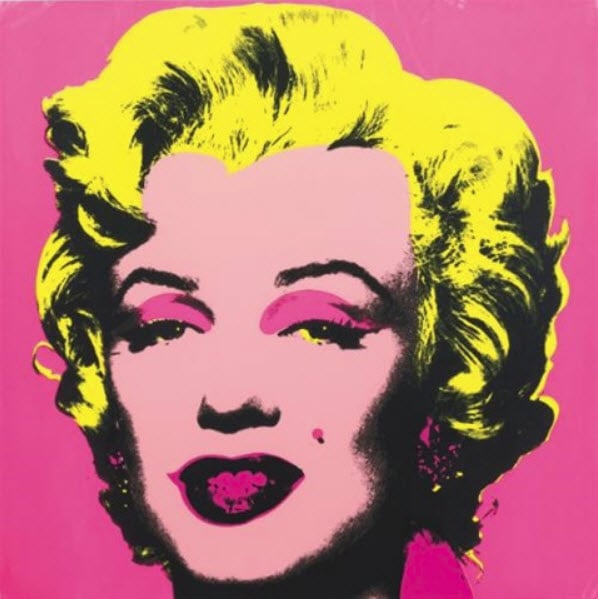

When Sotheby’s New York listed a 1967 set of Andy Warhol prints of Marilyn Monroe, lot 346 in a 2012 prints auction, it asked $1.4–$1.8 million for the lot, which had been consigned by an anonymous European collector. A cardboard box housing the prints was specified in Sotheby’s listing as part of the set.

New York dealer David Benrimon paid $1.65 million for the Marilyns—number 26 in an edition of 250—then sold them to Wyoming gallery Heather James Fine Art, which in turn sold the prints to its client, listed in court papers as One Sweet Dream, in California. (Behind One Sweet Dream is winery owner and art collector Cliff Lede, listed by Canadian Business among Canada’s wealthiest. His lawyers, Santa Rosa, California’s Geary, Shea, O’Donnell, Grattan & Mitchell, declined to comment.)

When Benrimon got the prints, the box was there; when they arrived at Heather James’s client, it was not.

After multiple unsuccessful appeals to the seller, Heather James brought a lawsuit, filed in New York State Supreme Court in April 2014 against Day & Meyer, Murray & Young, the highly regarded art moving, shipping, and storage company that was hired to transport the works. (A 2011 New York Times story described Day & Meyer as “the storage building of choice for many of New York’s wealthiest families, most prestigious art dealers and grandest museums.”)

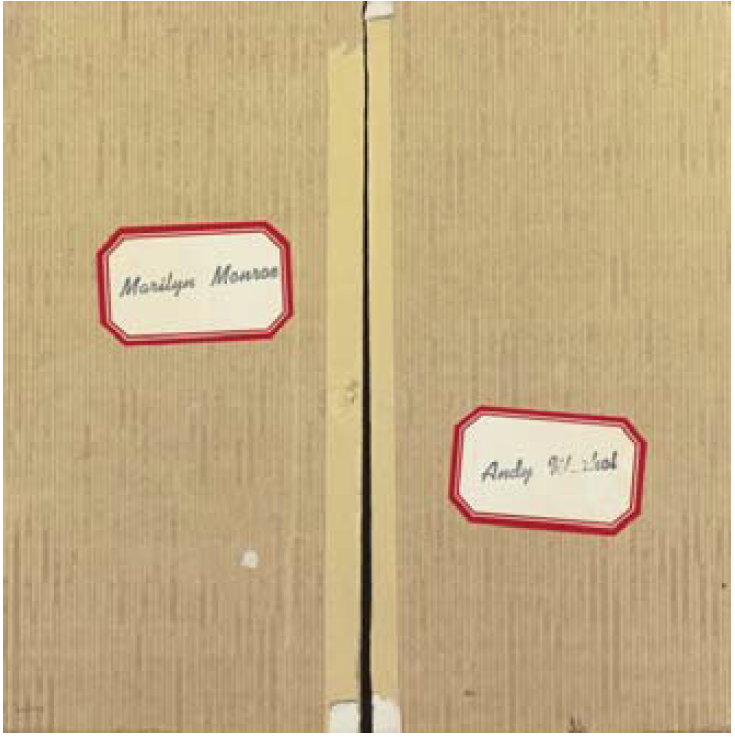

The box that originally housed the set of Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe (1967) at issue in the suit. From court papers.

Heather James Gallery’s complaint alleges breach of contract and negligence, among other charges. One Sweet Dream’s appraiser, New York’s Gurr-Johns International, names a retail replacement value for the box of some 15 percent of the value of the set, or $247,500. Heather James is suing for that amount plus interest.

James Carona, proprietor of Heather James, says in his filing that almost all of the 250 sets of Warhol Marilyns have been broken up, and that “finding a complete set with the same stamp with the original cardboard box is very rare indeed.” To his knowledge, there are fewer than 10 in existence.

Things allegedly went awry after the prints arrived at Day & Meyer. Heather James, in the gallery’s complaint, says it has done over $250,000 worth of business with the art service since 2005, without incident, but is now suing the company for recklessness, negligence, and gross negligence.

According to Carona, Day & Meyer first denied that it threw away the box, though security footage shows the box in Day & Meyer’s possession, complete with stickers. Robin Young, president of Day & Meyer, quoted in a 2014 deposition, says she’s “unsure” about whether the box was received. The company’s operations manager admitted that the box was “probably” discarded, says the gallery’s complaint. (Carona says the set is worth at least $175,000 less without the box, and has reached a separate settlement for that amount with One Sweet Dream.)

Meanwhile, Day & Meyer’s appraiser, Sharon Chrust, has a very different opinion of the box’s worth. She says in court papers that the boxes “have no determinable fair market values, are not artworks themselves and have no practical value or purpose because they are not suitable for use as print containers.” She concludes that they could account for about one percent of a portfolio’s value, in this case just $16,500.

Day & Meyer’s attorney, George G. Wright of New York, declined to comment.

A court date is set for Monday, November 6.