Reviews

Anicka Yi’s Art Is an Enigma Wrapped in an Ant Farm

The artist's Hugo Boss Prize show includes bacteria, bugs, and some vexing questions.

The artist's Hugo Boss Prize show includes bacteria, bugs, and some vexing questions.

Ben Davis

“Life Is Cheap,” the recently opened Guggenheim showcase of new work by New York-based artist Anicka Yi (b. 1971), is part of her reward for winning the 2016 Hugo Boss Prize (that and $100,000). When Yi won the prize last October, it seemed a bit of an upset. In retrospect, it shouldn’t have.

Yi’s art offers a perfect conjugation of a number of the concerns that are animating art right now: a rebooted interest in the politics of identity; a fey technophilia; a yen for fabulated narratives; and, with her use of weird, sometimes living things, what David Joselit calls recent art’s “emphasis on the agency of materials.”

“Life Is Cheap” is a chance to see how all this fits together—or doesn’t.

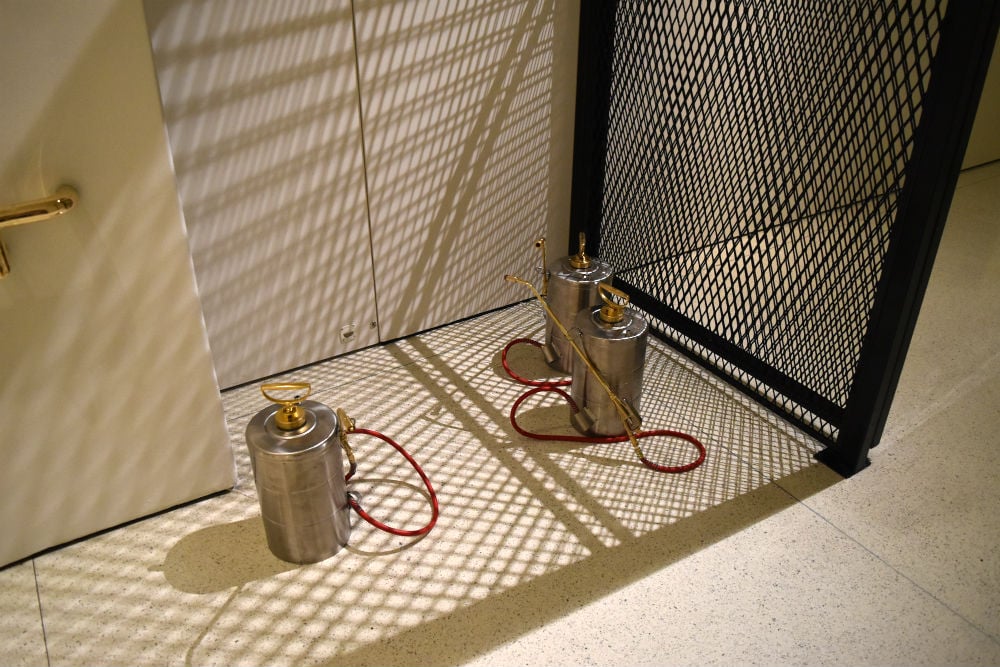

This is a small show, made in collaboration with a team of young scientists from Columbia University. As you enter, you pass Immigrant Caucus, a set of three canisters of the kind used by exterminators. They are displayed casually on the floor and fuming a scent that, the show text explains, has been synthesized from the smells of “Asian women and carpenter ants.”

Anicka Yi, Immigrant Caucus (2017) at the Guggenheim. Image: Ben Davis.

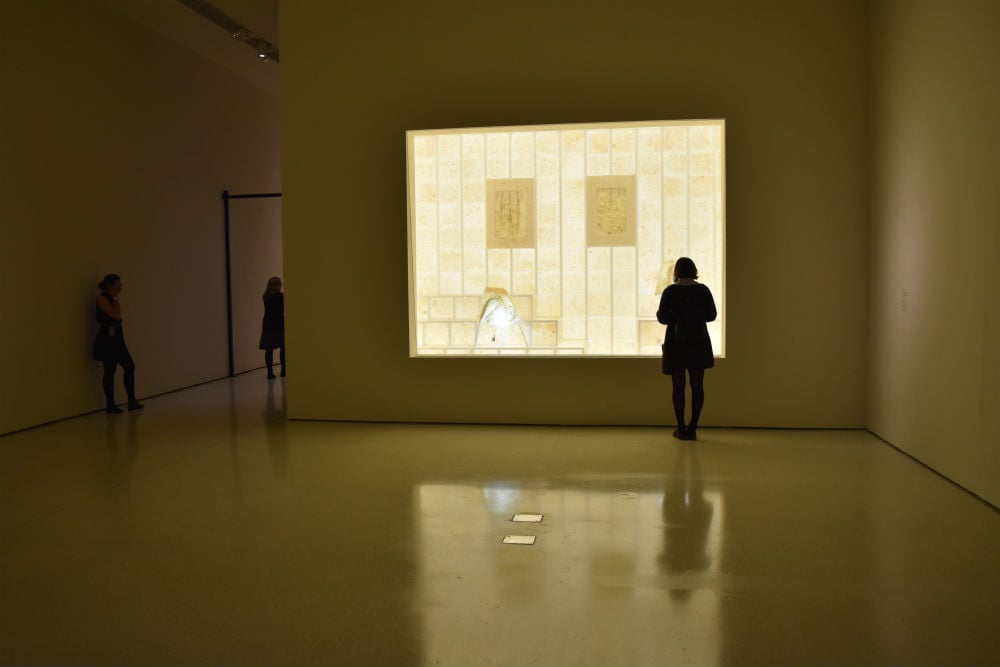

Beyond this are two installations, Force Majeure and Lifestyle Wars, which look like otherworldly shop-window displays. The former is a shallow, glassed-off chamber, containing two chair-like structures on stepped platforms. Every surface is overrun with speckled pink blotches which turn out to be blooms of bacteria, harvested from Chinatown and Koreatown (mixed with the odd green spot of mold). The refrigerated environment has been custom-designed to keep the bacteria in aesthetic stasis.

Anicka Yi, Force Majeure (detail) (2017) at the Guggenheim. Image: Ben Davis.

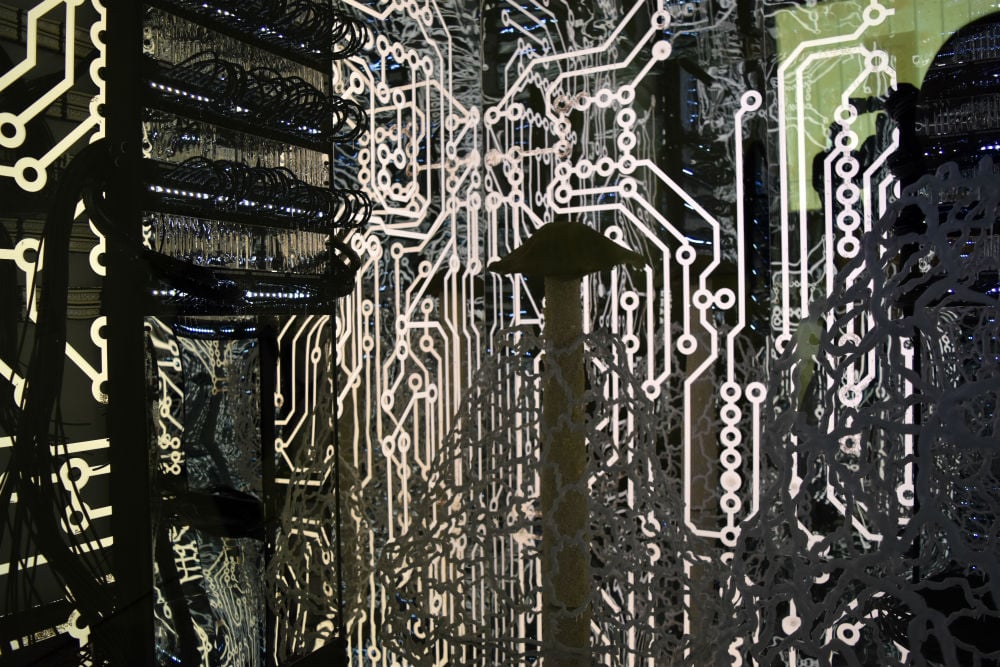

Across the small gallery, the other installation, Lifestyle Wars, is a cluttered diorama featuring sculptures of oversized mushrooms, blinking internet servers, mirrors, fake ice, cables, and living ants. The latter swarm through an oversized circuit-board pattern printed on the wall.

Installation view of Lifestyle Wars (2017) in “The Hugo Boss Prize 2016: Anicka Yi, Life Is Cheap.” Photo: David Heald, courtesy the Guggenheim.

Yi has spoken of herself as a “techno-sensualist.” She has said that her multisensory art is a timely response to a culture “overly dominated by the ocular sense,” on a mission to reconnect us with our other, overlooked senses, in particular smell.

I wouldn’t be the first to say that the anti-visual approach can lead, quite logically, to art that is more satisfying as a curatorial proposition than as a physical installation, and “Life Is Cheap” does feel a bit underwhelming on first brush. (Food for thought: Yi’s masterpiece so far, the absorbing The Flavor Genome, a highlight of the current Whitney Biennial, is a 3-D film—about as overbearingly “ocular” as you can get).

The complicating thing about Yi’s mission to take on art’s visual bias is that it arrives on the heels of more than a half century of conceptual art. And conceptual art was very specifically founded on Marcel Duchamp’s rejection of what he termed “retinal art.”

That brings us around to consider the less sensual, more critical claims of Yi’s art. She has spoken about developing a “biopolitics of the senses,” meaning, in the words of the introductory text panel for “Life Is Cheap,” that she wants to generate critical reflection of “how assumptions and anxieties related to gender, race, and class shape physical perception.”

Anicka Yi, Force Majeure (2017) at the Guggenheim. Image: Ben Davis.

Just how exactly “Life Is Cheap” might accomplish this latter is not really spelled out anywhere, as far as I can see. Upon investigation, one has to imagine that the entry point is meant to be the stress put onto the Asian-ness of her materials.

Even if it is pursued with a pokerfaced scientific literalness, Yi’s claim to distill the unique smell of “Asian American women” must be meant as a kind of ruse. One imagines that Yi can only be asking you to examine how your assumptions about the ‘essence’ of Asian women shape your perceptions here. The work makes a claim on your intellect, not your senses. (Truth be told, Immigrant Caucus doesn’t smell like much.)

But then, you have to ask: What is the deal with the ants?

Squinting hard at “Life Is Cheap” (intellectually), I wonder if there is some kind of vague background reference to Western stereotypes about Asian cultures as “worker ants.” That seems like a stretch, but… maybe?

But no. Returning to the official explanation, we read that Immigrant Caucus’s perfume is also being pumped into Lifestyle Wars’s alien ant farm environment, thereby “creating the possibility of a shared psychic experience between ant and human.” As for the specific symbolism, the text explains that ants “interest Yi because of their intricate division of labor and matriarchal social structure, as well as the sophisticated olfactory system that guides their behavior.”

As far-out as these claims are, they would seem to be sincere. They dovetail with Yi’s established feminist and “techno-sensualist” interests.

The upshot is that “Life Is Cheap” calls upon you to invest in science’s ability to stimulate human-ant communion, but also asks you to have a serious conversation about racial stereotypes. It both claims to reconnect you imaginatively with some kind of lost kingdom of multi-sensory, extra-human knowledge, and to force you to scrutinize those senses critically for their very-human cultural biases. The “techno-sensualist” and the “biopolitical” pieces don’t quite align. They’re in tension.

You could say that this makes the whole affair seem a little self-indulgent. Nevertheless, I find its brazen oddness lovable—and to be generous, you might also argue that its contradictions are what make it particularly of-its-moment.

Classic-model Conceptual Art took great inspiration from both Anglo-American analytic philosophy and French semiotics. Yi’s art, for its part, has benefited greatly from its resonance the various “new materialist” philosophies that have recently become the guiding light of almost every art biennial, a strange kind of philosophical animism speculating on the independent life of things beyond human cognition.

Anicka Yi, Lifestyle Wars (2017) at the Guggenheim. Image: Ben Davis.

Yi doesn’t dwell on the relationship of text to image in the mode of classical Conceptual Art. And yet, in a kind of return of the repressed, a particular kind of writing does pop up around Yi, one more proper to the contemporary philosophical vogue.

As Alice Gregory recently observed in her profile of Yi, her wall texts characteristically read “more like an alien shopping list than an informational label.” Critical writing on Yi has a tendency to linger on lists of her materials with a specificity not equal to what might be known through the senses (e.g. “recalled powdered milk, antidepressants, palm tree essence, sea lice, a Teva sandal ground to dust, and a cellphone signal jammer.”)

As it so happens, those trendy “new materialist” philosophers also have a notable habit of studding their texts with lists of discordant nouns, such as “aardvarks, baseball, and galaxies; or grilled cheeses, commandos, and Lake Michigan” (in Andrew Cole’s homage). The trope of reeling off these “bestiaries of things” is so common that it has even acquired a nerdy technical name: the “Latourian Litany” (after philosopher Bruno Latour).

You can see Anicka Yi’s pointedly disparate art as “Latourian Litany” in sculptural form.

Anicka Yi, detail of Lifestyle Wars, showing ants. Image: Ben Davis.

In philosophy, the tic is meant to convey an adventurous theoretical ecumenicalism, a cosmic viewpoint that transcends the everyday categorization of things. As for art that retraces its path, it has the everyday problems of fabrication and presentation to think about.

And so, “Life Is Cheap” may be genuinely useful as an illustration of the direction that such thought points in the gallery: towards an art of materials that isn’t really about materials, and an art of ideas that isn’t really about those either.

“The Hugo Boss Prize 2016: Anicka Yi, Life Is Cheap” is on view at the Guggenheim April 21–July 5, 2017.