Art World

The Whitney Nails a Balancing-Act Biennial

It feels more like the last Biennial of the Obama Era than the first of the Trump Era.

It feels more like the last Biennial of the Obama Era than the first of the Trump Era.

Ben Davis

Here’s a super-short, bottom-line, first-impression review of the Whitney Biennial 2017: It’s good.

Tasked with organizing the first edition of the museum’s signature American art survey in the fancy new downtown headquarters, curators Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks have turned in a stylish and professional affair. With 63 artists and collectives, it contains a lot without feeling fatiguing or over-burdened (though I will—full disclosure—have to go back to review all the film in it, which could not be experienced in the four hours of the press preview).

Asad Raza. Root Sequence, Mother Tongue (2017). Photo: Henri Neuendorf.

Lew and Locks feel as if they have arrived at a well-calibrated model of what the Whitney’s always-controversial signature event should do. There’s enough cool painting to satisfy that crowd, but also enough new media and other novelties to satisfy that other crowd. It has big, obvious set-pieces, but also moments that will reward deeper looking and deeper thought.

Shara Hughes, In the Clear (2016). Collection of the artist; courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner.

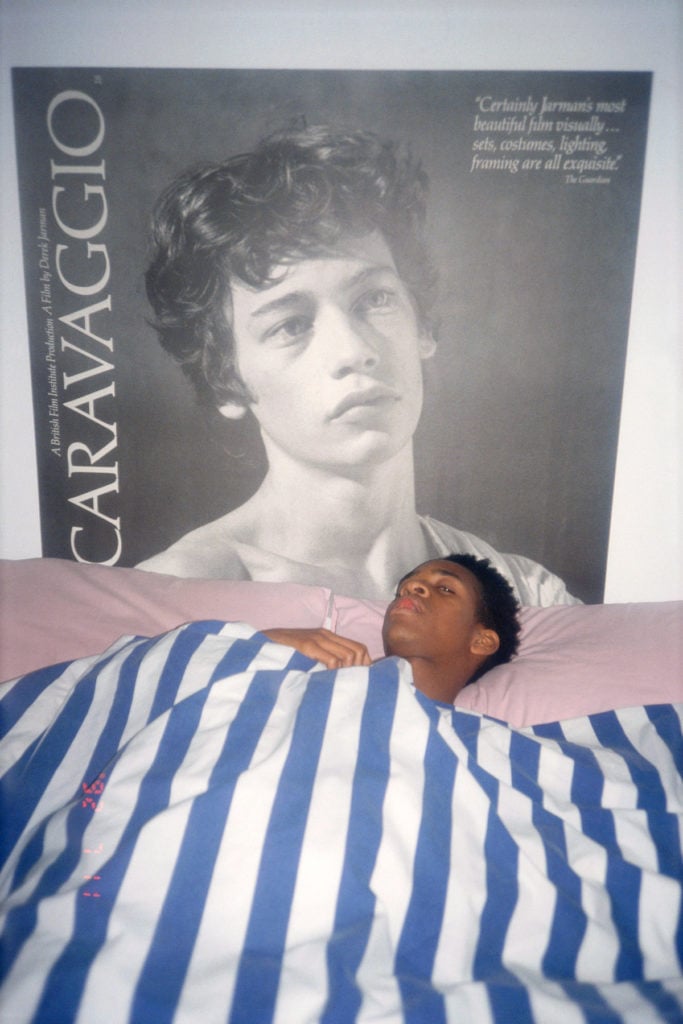

The Biennial has wacky moments (Samara Golden’s mirrored environment, which makes it appear as if you are staring down the atrium of an endless, disjointed office tower), and pretty moments (Shara Hughes’s suite of lush, florid canvasses, like windows to a more tranquil world), and gee-whiz wow moments (Anicka Yi’s high-production 3-D film, The Flavor Genome, a brainy and delirious video essay splicing science and myth into something flamboyantly singular), and tender moments (Lyle Ashton Harris’s Once (Now) Again, a slideshow environment flickering through bracingly personal photos of black, gay life in the 1980s and ‘90s).

Lyle Ashton Harris, Lyle, London (1992). Image courtesy the artist.

If the affair errs on the side of seriousness, that’s as it should be, as any Biennial has to have enough gravitas to make it feel like the Serious Statement that it is expected to be.

The only mild complaint about the Lew-Locks formula is that it feels, maybe, a little formulaic, like the show doesn’t exactly have a big hook or curatorial conceit beyond smart taste-making and the expertly executed balancing act. Still, as far as the Consumer Reports portion of this review goes, that’s probably enough: The show stacks up well against its competitors; it is a very enjoyable, well-orchestrated survey of contemporary art.

Of course, in some way, The Political Moment is meant to stand in as the hook. “The Biennial arrives at a time rife with racial tensions, economic inequities, and polarizing politics,” the show pamphlet tells us, in that tone of non-committal commitment particular to serious art exhibitions, “and many works in the exhibition challenge us to consider how these realities affect our sense of self and community.”

The press build-up to this Biennial has stressed that the show was organized in the thick of the diabolical atmosphere of last year’s election, promising a timely reply to the contemporary shift in politics. Yet everything about the actual atmosphere of the 2017 Whitney Biennial makes me remember what a Red Wedding the election really was.

A bright line divides the way the world looked in mid-2016—preoccupied with Trumpism as a hateful novelty act, whose endgame was actually Trump TV—and early 2017. The two periods are separated by about a million think pieces about “cultural bubbles,” “alternative facts,” and 1930s Germany; by the Women’s March super-rallies and the desperate turmoil of the airport protests.

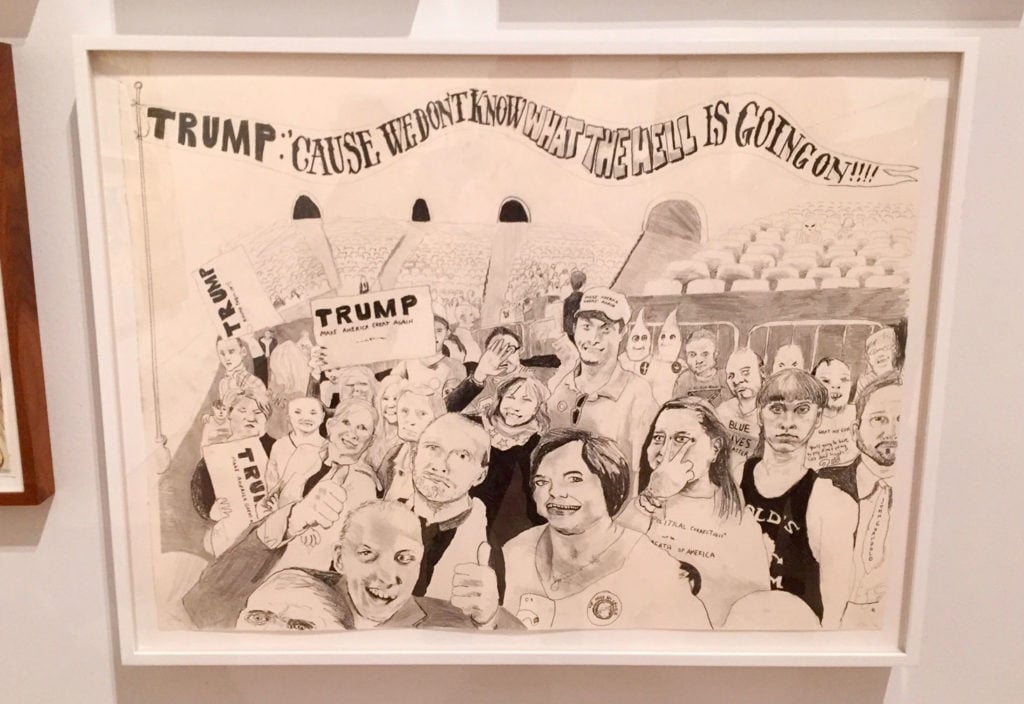

Had the curators of the 2017 Whitney Biennial been doing their research just a few months later—or had they panicked in the home stretch—my guess is that this show would have had a very different, less even-keeled tone: more strident, more apocalyptic. My guess is we’ll be seeing a lot of strident and apocalyptic in the near future. (Painter Celeste Dupuy-Spencer’s drawing of a Trump rally, replete with KKK members and blankly staring murderer Dylann Storm Roof, is one of the few bits of really explicit red meat.)

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, Trump Rally (And Some of Them I Assume Are Good People) (2016). Image: Ben Davis.

And so, it is best to consider the Whitney Biennial 2017 not as the first Whitney Biennial of the Trump Era, but as the last one of the Obama Era. At the very least, it straddles the two. And though I do think the bar for serious has been raised, I actually also think this show’s slight remove from the new moment plays the positive role of giving already-needed perspective.

An All-Trump, All-the-Time news cycle tends to reduce every evil to the personality of one man, glossing over all the other, much longer-range political dynamics going on. And indeed, contemporary art has been working through a lot of baggage of its own, baggage it still has to work through before it can have any credibility as a torch-bearer for the #Resistance.

The best example of such an ongoing conversation, productively continued here, is provided by the studied diversity of the show itself. Lew and Locks—and the Whitney as an institution—have clearly learned from the quite bitter controversies over race and representation that haunted the previous incarnation of the Biennial.

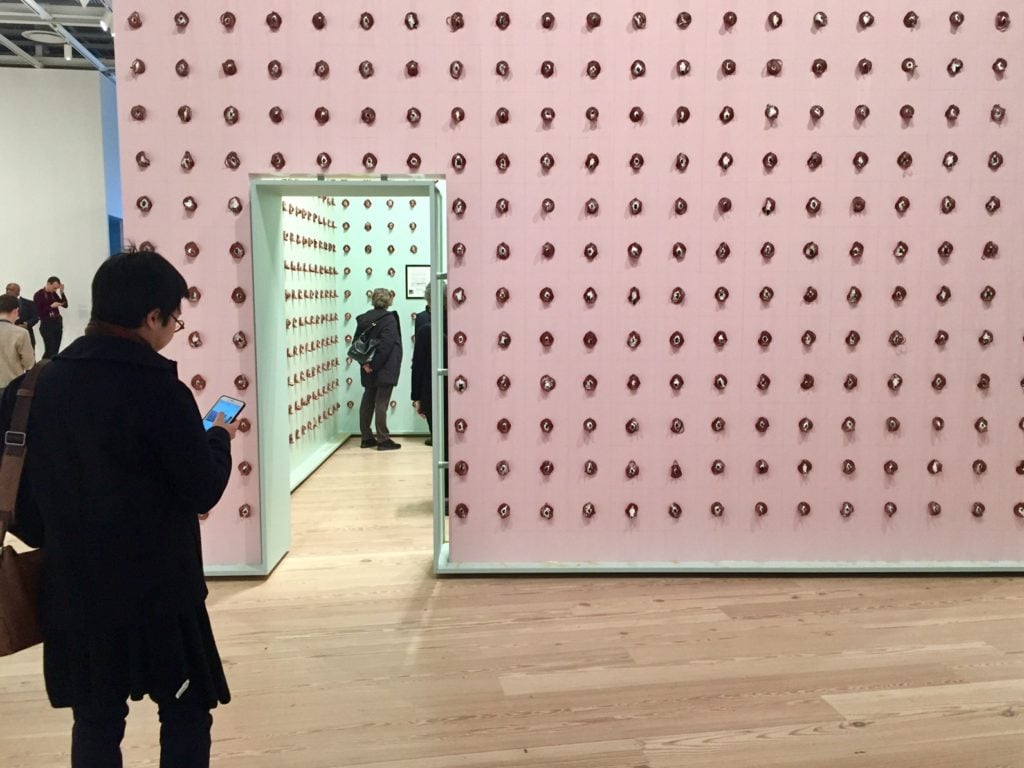

Installation view of William Pope.L, Claim (Whitney Version) (2017). Image: Ben Davis.

One of the senior figures here is William Pope.L, the consistently discomfiting Chicago-based African-American artist whose fifth-floor installation, a kind of free-standing room, is adorned with a number of actual, fleshy, putrefying baloney slices, nailed to its walls in grid. Pope.L claims that their number corresponds to a percentage of the population of New York that is Jewish, via some slightly unclear formula.

It’s a deliberately wild idea, but also a physical metaphor in the biennial of the kind of double bind these events pose when it comes to minority artists: it’s absurd to count, yielding up all kinds of questions about who counts and how, and by what metric; but it’s also absurd not to. Either way, it stinks of baloney.

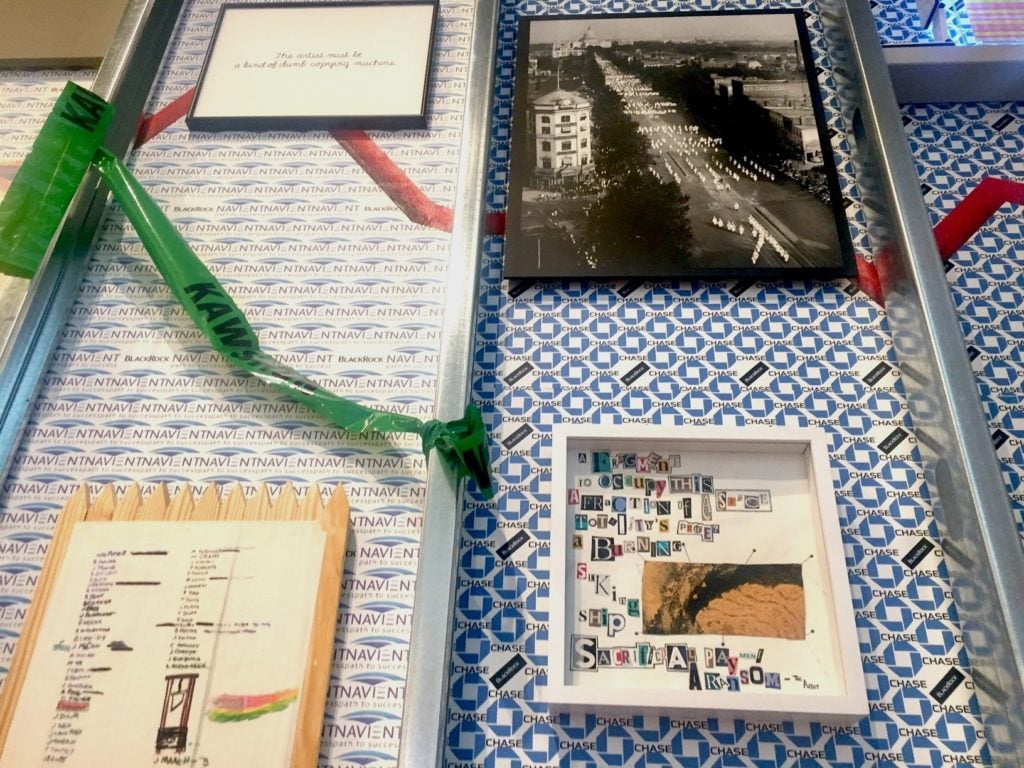

A second obvious example of a looming, still-unfolding conversation comes via the inclusion of Occupy Museums, an activist para-art group that sprung from the side of Occupy Wall Street. Here, they have slashed open one wall, leaving a gaping, jagged rift that doubles as an architectural infographic, illustrating the escalating profits of the behemoth financial firm BlackRock.

Occupy Museums, Debtfair (2017). Photo: Henri Neuendorf.

Hung within the space opened up by the gashed wall are a variety of works by artists, sourced by Occupy Museums through a national call, each one of whom claims to be in some form of crippling debt to one of three financial institutions owned by BlackRock. These artists’ often upsetting testimonies about their predicaments and how they arrived there are available through accompanying projections and literature.

As for their works, they can be purchased for the cost of one month of the artist’s debt repayment (hence the title, Debtfair).

Detail of works displayed in Occupy Museum’s Debtfair installation. Image: Ben Davis.

This Occupy Museums installation is the product of at least five years of fine-tuning ideas and organizing to prod at the power structures of the art industry. It is, in my opinion, excellent, a complex idea, elegantly and memorably presented without losing its punch.

At this point in time and in this particular museum context, I actually think it would be easier to make the fine-art equivalent of clickbait denouncing ignorant Red State reactionaries than it is to continue this conversation about what goes unsaid within the museum audience itself: that the whole art party—its entire self-perception as a bastion of outspoken free speech and cosmopolitan tolerance—is marinating in a farrago of long-brewing inequality, economic entitlement, and soured dreams.

Of course, contemporary art in general, and biennials in particular, already have the bad tendency to venerate self-serious riffs on “the political” all out of proportion to any real-world significance (what New Yorker scribe Peter Schjeldahl dubbed “festivalism“). The present moment, when “activism” is suddenly not just in-demand but positively chic, is likely only to exaggerate this unfortunate tendency.

Visitors experiencing Jordan Wolfson’s Real Violence (2017) virtual reality artwork. Photo: Henri Neuendorf.

The other sure-to-be-debated work from the 2017 Biennial will be art star Jordan Wolfson’s vivid virtual-reality experience Real Violence, and it might well serve as an illustration of exactly this pitfall. Wolfson is not an artist you would particularly associate with political posturing. On the whole, he prefers to swing for a kind of visceral, gut-level aesthetic seduction. His fondest wish seems to be becoming “Nasty Jeff Koons.”

In fact, now that I mention it, Real Violence aims for the “I can’t believe he went there” quality of Wolfson’s avowedly favorite Koons work—the “Made In Heaven” porno photos—only with ultra-violence instead of graphic sex. A VR helmet plops you onto a city street where you watch the artist, who stares directly at you as if to say “I’m doing this for you,” a device Wolfson likely takes from Koons’s fourth-wall-breaking gaze in “Made in Heaven.”

Another man kneels beside him. And then, before you can even fully acclimatize yourself to the VR, you watch the artist take the bat and begin to pound his companion’s head until it is a slushy red pulp bleeding out on the sidewalk. The sound, aside from the convincing thump of bat against bone, is of Hebrew prayers, evidently read by Wolfson himself.

The work is repellant. Which—I know, I know—is the point. But at a time of actual anti-Semitic threats and actual mob violence, mining the subject for a hyperreal high feels more than lame and less than cheap. It gets you talking—but mainly about how shallow art can be.

So, the Whitney Biennial 2017 offers some object lessons, both on things art has learned, and the things it has still to learn.

The Whitney Biennial 2017 is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, from March 17 to June 11, 2017.