Anish Kapoor is rarely out of the headlines. Whether it is thanks to a prestigious public commission, or a bold act of protest, he is one of the most prolific and most vocal contemporary sculptors of our time.

His gallery shows and public sculptures have made him one of the world’s best-known living artists, and along with his outspoken nature, Kapoor is firmly at the forefront of contemporary culture in the UK.

Kapoor moved to London in the early 1970s, having grown up in Mumbai, India. He first studied at Hornsey Art College before graduating on to the Chelsea College of Art. Influenced by Modernist and Minimalist sculpture, he later explained his desire to look a little deeper than the famous artists of the day.

“Donald Judd used to say that art doesn’t get made, it happens,” Kapoor told the Guardian in 2008. “The implication of that is that the studio is a place of a certain kind of practice. And there, things occur that hopefully have deep quotidian recall—but are not directed by the quotidian world. So the post-Warholian notion that everything in the world is all art—it’s fine, but what it avoids is the truly poetic, or the poetic of a slightly different order. And it’s that order I am interested in.”

Anish Kapoor, Untitled (1990)

Photo: courtesy Gladstone Gallery

Kapoor’s first major exhibition was at the Hayward Gallery, as part of their show “New Sculpture,” which was held shortly after he left college in 1978. At this time, the sculptor was working with dry pigment, which he would shape into intricately tiered and textured works rendered in impactful, saturated colors.

Having gained recognition during the 1980s, Kapoor became represented by Lisson Gallery, and his career began to take off in earnest in the early 90s when he represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1990. There he was awarded the Premio Duemila, and he then went on to win the prestigious Turner Prize the following year, in 1991.

Anish Kapoor, Non-Object (Spire) (2008)

Photo: courtesy Gladstone Gallery

It was over a decade later that he truly broke into the mainstream, winning over the British art-going public with the installation of his monumental sculpture, Marsyas (2002), in the turbine hall at Tate Modern. The enormous, red, funnel-like structure—which consisted of one piece of PVC stretched over three rings, at a length of 3,400 square feet—is still remembered as one of the most successful and beloved installations in the famed exhibition space.

By the mid-90s, Kapoor had begun to work with stainless steel, creating dramatic, mirrored works in concave and convex forms. Perhaps his most famous work in this material is Cloud Gate (2006), or the “Bean” as it is affectionately nicknamed, installed in Chicago’s Millennium Park. This popular sculpture is just one of many public commissions, such as Sky Mirror, which has been reproduced several times, and can be seen in London’s Kensington Gardens as well as at Rockerfeller Center in New York. Another famed public work is the large, twisting metal structure titled ArcelorMittal Orbit (2012), which is on view at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in Stratford, London.

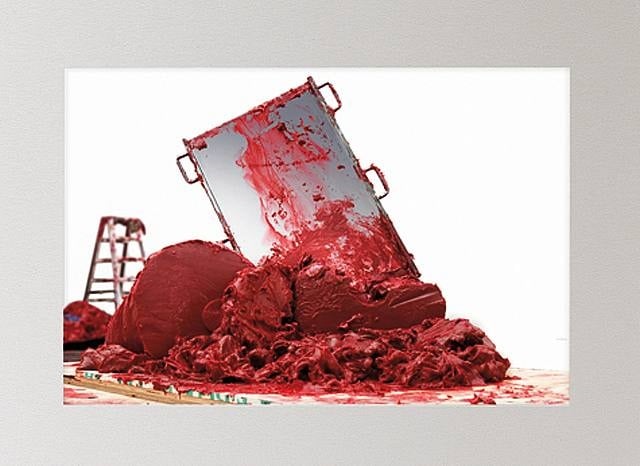

Anish Kapoor Svayambh (2007)

Photo: Schellmann Art + Furniture

Kapoor also works with more impermanent materials, such as wax, which he uses to create a fleshy and meat-like consistency in both large-scale installations and in hung works.

Regardless of their material, although Kapoor’s sculptures tend to be very beautiful to look at, they refuse to sit quietly and avoid controversy. Despite the fact there is no figurative content or explicit message in his work, it tends to provoke strong reactions—the strongest perhaps being the furor over his piece Dirty Corner (2015), installed at his solo exhibition at the Palace of Versailles this past summer.

Anish Kapoor Title to be Confirmed (2009)

Photo: courtesy Regen Projects

When he informally renamed the monumental iron work “The Queen’s Vagina,” this enraged just about everyone from art lovers to politicians and, unfortunately, the French far-right. The sculpture was repeatedly vandalized with anti-Semitic hate speech (Kapoor is of Indian and Jewish parentage)—and when the artist refused to remove the graffiti as a form of protest, there was a threat of legal action from the authorities. A compromise was eventually reached, and the graffiti was covered in gold leaf.

“We lost, can you believe it?” Kapoor told artnet News, in October 2015. “Some very racist, in my view, deputy from parliament took me to court. We were forced to hide the graffiti. It’s a terrible, sad thing.”

Unsurprisingly, this has done nothing to dampen Kapoor’s political spirit, and he has continued to speak out on a variety if issues throughout 2015. From the “walk of compassion” he undertook with Ai Weiwei in support of Syrian refugees, to comparing the current Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, to the Taliban in a Guardian editorial, Kapoor has remained a vocal and passionate defender of free speech and human rights.

Whether he is tackling oppression head-on or creating inventive new art, Kapoor does this with a verve and confidence which is hard to ignore. You could always follow him on his Instagram, @dirtycorner, if you’re curious to see where his artistic practice takes him next. As the turbulent world stage shows no sign of calming down, it seems likely that Kapoor will have plenty to say.