Art World

What Rodin Taught Anselm Kiefer About Making Art in an Age of Destruction

On the 100th anniversary of Auguste Rodin's death, the Barnes Foundation opens a show looking at the French sculptor's influence on the German painter.

On the 100th anniversary of Auguste Rodin's death, the Barnes Foundation opens a show looking at the French sculptor's influence on the German painter.

Rachel Corbett

Auguste Rodin and Anselm Kiefer are not an immediately obvious pairing for an exhibition commemorating the centenary of Rodin’s death, one hundred years ago today. One died at the end of the First World War, the other was born into the second. Rodin watched the Germans bomb his beloved cathedrals in France while Kiefer grew up playing in the rubble of German buildings in the late 1940s.

Both men are, however, artists of towering stature, who make monumental works, often influenced by the natural world. They lay their creative processes bare in their paintings and sculptures, and allow “incomplete” fragments to tell their own stories. As the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia opens “Kiefer Rodin” (through March 12, 2018), which traveled from the Musée Rodin in Paris, we spoke to Kiefer about what creative traits he shares with the French master and how their work reflects the politics of their changing times.

What was your first introduction to Rodin?

My first access to Rodin came when I was 14 or 15. I read Rainer Maria Rilke’s [1903 monograph] about Rodin. It has a wonderful first sentence: “Fame is nothing but the sum of all the misunderstandings that gather around a new name.” It’s nice, no? There were some pictures of the sculptures in the book and that was the first time I was really connected with Rodin.

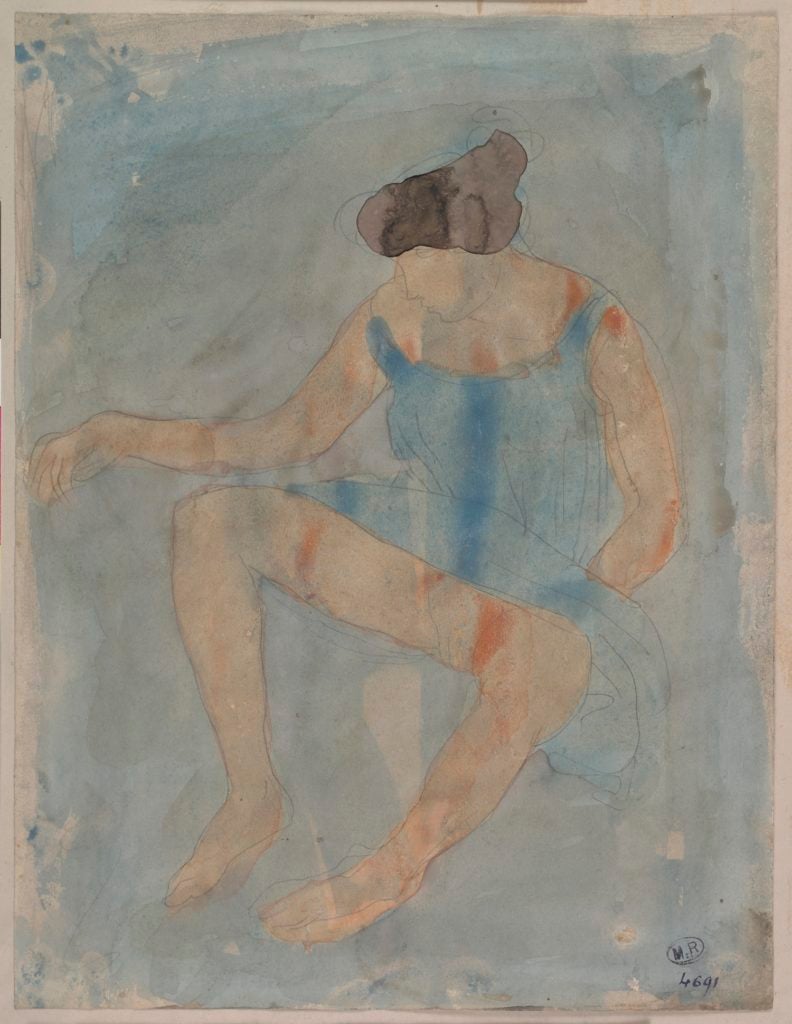

Auguste Rodin’s Seated Woman with Garment Raised above Her Thighs (undated). Photo by Jean de Calan, © Musée Rodin.

I’m interested in how influence transmits between artists, from Rodin to Rilke, and now of course from Rodin to you a century after his death. What did you learn about yourself as an artist from this process?

It was more a discovery of similitudes. The first time I saw Rodin’s work I was 17 years old and in Paris. I had never seen the drawings before—they were too explicit to be shown. But later, when I did watercolors—and I’ve always done watercolors, not only the big paintings—I discovered my habit to make them look like Rodin in a way. He’s much better, but it looks like it. My teacher, Joseph Beuys, some of his watercolors look like Rodin’s as well. So Rodin is going through all of these artists.

Rodin was equally passionate about gothic cathedrals as he was female nudes, but he never explicitly combined the two in his work. You do. Why did you want to combine these two subjects in your watercolors?

It’s very simple. The Musée Rodin came to me and said they wanted to do a show about Rodin’s book Les Cathédrales de France, and in this book he speaks a lot about women, sometimes in a chauvinistic way. Did you read this book?

Yeah. He talks about how the cathedral looks like the body of a woman.

He talks about the young girls of the country, like, ‘They are so perfect, so different from girls in Paris.’ It’s very strange. It’s a bit like Germany in the 1930s. But I liked the idea of how he compared the structure of the cathedral to the body of a woman. For this reason, I thought it was fantastic and I would do something with it. Sometimes you just need a little thing to start.

Anselm Kiefer’s Les Cathédrales de France (The Cathedrals of France) (2013). Photo by Charles Duprat, © Anselm Kiefer.

You title your large-scale canvases so literally: Auguste Rodin: les Cathédrales de France. Yet they are not exactly cathedrals, even if they have architectural elements underlying them.

These are the cathedrals of Auguste Rodin. He writes about how the cathedrals shouldn’t be restored. They should stay in their time and that’s what is very similar to my thinking. I don’t think in results, I think in the process. When I do a painting I destroy it immediately, so I’m an iconoclast. Real painters are iconoclasts. Because they destroy it and then years later they have resurrections. So here you see the south of France [where Kiefer owns a complex of studio buildings]. Some fall down, some I make fall down. So it’s always a process of falling down and resurrection. So the Cathédrales de France for me is not Notre Dame in Paris, which is well kept, like Disney a little bit. For me, the process of getting old, of falling down—that is the Cathédrales de France.

Anselm Kiefer’s Les Cathédrales de France (The Cathedrals of France) (2016). Photo by Georges Poncet, © Anselm Kiefer.

Rodin published the Cathédrales de France at the onset of World War I. He was devastated by the German bombings of the cathedrals. Now we have ISIS attacking historical monuments in the Middle East and right-wing nationalists waging new culture wars in the West. How do you think the rise of extremism is affecting art today?

We live in a very dangerous period. It’s horrible what’s happening in the Netherlands, in Belgium; in France, it was close; in Austria and in Germany, the new fascist party is getting into parliament. I have always said, ’45 is not the year where it resets to zero. It’s not true. We don’t start over. For example, no lawyer or judge was condemned after the war because they helped each other. I always think in each country there is the bottom of society—the morass. It’s always there and sometimes it comes up. It’s not like after a war or because we have democracy now it’s gone. It stays there and something will bring it up. It’s always a very dangerous matter.

What is the relationship to Rodin in your vitrine works?

I’m always fascinated by the process of doing sculpture. I don’t do it myself, but at the bottom [of the vitrine] there’s a form, and it’s a transitional moment. It’s not from Rodin; I got them from Paris at this big house where they have all the molds of artists who’ve passed through over centuries. I said, “They’re so beautiful, can I have some?” And they were happy because they had so much stuff. They don’t know who the artists are, they just collect them. So I started working with them.

Anselm Kiefer’s Die Walküren (The Valkyries) (2016). Photo by Georges Poncet, © Anselm Kiefer.

Do you have a favorite work by Rodin?

It’s very much the watercolors. These I like the most because it’s something I couldn’t do. You know, he was not looking at his paper when he drew. Isn’t that wonderful?

Yes, he always kept his eyes on the object. Can you draw like that?

No. I just saw the Michelangelo show in New York and was so impressed. The Old Masters were so trained in drawing. They had to do it every day because they had no photos. So you had to draw or model with your hands. They were so well trained. They knew what I liked because they have thousands of drawings at Musée Rodin. At a certain time, it was not possible to show them; they were too explicit.

How do you think the post-digital age, and all the photos that are available today, is effecting sculpture?

We need to look at the origins. You can’t show work on your iPhone. It’s very important to look at things in reality. The digital age doesn’t help much for the presentation of art.

There’s been a lot of talk about how your recent show of watercolors at Gagosian incorporated so much color.

It’s not new. I did watercolors since I was a small boy. Journalists—excuse me, but journalists will stick with a thing, and I’m the big painter guy. I had a show at the National Library in Paris two years ago, and there were thousands of books that I did myself, so that’s most of my work—the books—not the big things.