Politics

What Are the Biggest Challenges Facing UK Museums? Brexit and Budget Cuts, New Report Says

The report tallies government spending on UK museums for the first time.

The report tallies government spending on UK museums for the first time.

Javier Pes

How much public money is spent on museums in England? The figure has been officially calculated for the first time in a government-initiated report, which was published this week. The nation spends around £844 million ($1.1 billion) of taxpayers’ money each year on around 2,600 public institutions—down more than £100 million a year ($131 million) compared to a decade ago.

The $1 billion total is still roughly the cost of a spending spree on a top-dollar Leonardo, Picasso, and Basquiat at auction—but a bit less than the amount Abu Dhabi has spent on building, branding, and programming its new Louvre.

The Mendoza Report, named after the businessman and philanthropist Neil Mendoza, who led the review, released its 110-page survey on November 14. The institutions consulted range from three of the world’s most visited—London’s Tate Modern, National Gallery, and British Museum—to shiny new modern and contemporary galleries in the regions, such as Turner Contemporary in Margate, the Hepworth Wakefield, and Nottingham Contemporary, along with small, local museums.

On balance, the report was good news for Prime Minister Theresa May’s Brexit-dominated Conservative government. Mendoza found that “the breadth and quality of exhibitions and programming of England’s museums have been transformed over the past 25 years.” He added that they are “integral” to promoting Britain on the world stage through their partnerships and exhibitions with museums abroad, emphasizing China, Brazil, and India.

But challenges remain. Below, we look at the biggest issues facing UK museums discussed in the report—and the ones it glosses over.

After a decade of austerity, Mendoza pours cold water on hopes that the government’s autumn budget on Wednesday, November 22, or Brexit might lead to additional funding for museums. “It is unlikely that there will be significant additional money available for the sector in the immediate future,” the report says.

Mendoza diplomatically describes museum funding during the past decade of austerity as “fairly flat… although reduced in real terms.” The cut was, in fact, around £109 million ($143 million), a 13 percent decrease after accounting for inflation (£829 million in 2007–8 to £720 million in 2016–17).

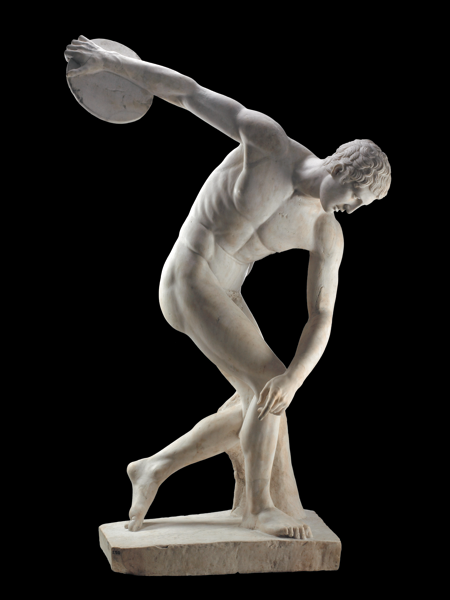

The BM is flexing its soft power in Mumbai, sending its marble statue of a discus-thrower to “India and the World”

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The real windfall for museums over the past two decades has been the more than £2 billion ($2.6 billion) they have received via the National Lottery, which was launched in 1994 by a Conservative government.

Over the past decade, the Heritage Lottery Fund has awarded museums an average of £91 million ($120 million) per year. Most of the money has been dedicated to expansions and other capital projects; the lion’s share has gone to a few big London institutions.

Still, lottery funding has not made up the shortfall in public funding—nor was it originally intended to. (The lottery was meant to provide “additional,” not alternative, funding, though the report hints that this might change.)

With public funding squeezed, wooing sponsors will become all the more crucial, whether it be Hyundai, which helped the Danish collective SUPERFLEX transform Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall into a free art playground (until April 2), or BP, which has helped finance the British Museum’s new exhibition on the Scythians of ancient Siberia (until January 14).

Martin Roth accepts the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2016 prize from the Duchess of Cambridge on behalf of the V&A. He left soon after, citing Brexit among his reasons. Photo: Matt Dunham – Pool/Getty Images.

The Mendoza Report does not dwell on Britain leaving the EU. But a number of respondents expressed concern over the impact that Brexit would have on museums, “particularly in terms of workforce.”

The steady brain-drain from Britain’s top art museums could indeed be accelerated by Brexit. Concerns have been raised about attracting and retaining foreign-born staff after the UK leaves the EU in 2019. The late Martin Roth cited Brexit as a reason why he stepped down as the director of the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2016.

Nicholas Serota, the former Tate director and current chairman of Arts Council England, which contributed to the report, has said he hopes that the government recognizes that to ensure the richness and complexity of Britain’s cultural offerings, “we have to be able to continue employing people from the EU.”

As the majority of museums’ operating budgets are dedicated to staff salaries, “flat” public funding also results in continued low pay for many, even those in top posts. When compared to salaries of colleagues in art museums in North America, the gulf is vast.The increase in short-term contracts for staff is mentioned but not outsourcing, which led to a protracted strike at the National Gallery in 2015 when some front-of-house roles were privatized.

Serota’s salary, plus bonus, was £193,977 ($256,000) in 2015–16 after more than nearly three decades at the helm of the Tate. By contrast, artnet News reported that Glenn Lowry, the director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, received $2.1 million in salary, bonus, and benefits in 2013.

The report says there is a “pressing need” for excellent leaders with the right skills to guide museums. But with pay low and continual budget cuts, it will be no surprise if more directors and curators head abroad, following the likes of Sheena Wagstaff (who left Tate for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York); Jessica Morgan (Tate Modern to Dia Art Foundation), and Chris Dercon (Tate Modern to Berlin’s Volksbühne).

Staircase to the V&A’s new, supersized exhibition galleries ©Hufton+Crow, courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum.

The review declined to re-examine the UK’s policy of offering free entry to collection galleries at national museums. But the policy has its critics from within the museum community. Mendoza admits that many would like to see free entry “discussed and challenged.” It is highly unlikely to be, although it grates with some running independent museums, which depend on charging visitors.

On the other hand, the free entry policy has helped the likes of Tate Modern, the British Museum and the National Gallery in London become some of the world’s most visited. But a discussion of the high costs to see special exhibitions in free-entry museums is strangely absent in the Mendoza report.

Those prices are steadily rising. Tickets to see Tate Modern’s latest exhibitions are £17.70 ($23). To encourage visitors to see “Modigliani,” which opens on November 23, and either its Ilya and Emilia Kabakov or Russian Revolution shows, the gallery is offering a combined ticket of £25 ($33) plus a drink. To see all three would cost more than £42 ($55). Upriver at Tate Britain, a combined ticket for “Impressionists in London” and Rachel Whiteread costs £29 ($38).

This summer, the V&A raised eyebrows by hiking charges for the final weekend of its Pink Floyd show to a record-breaking £30 ($39). Before the run was extended, the full adult price to see stage costumes and ephemera was £22 ($29). The British Museum and National Gallery both charge around £16 ($21) for access to special exhibitions.

There has long been mutterings about whether the big national museums on London’s tourist trail should charge overseas visitors, who accounted for more than 60 percent of the nearly 13 million collective visitors to the British Museum and National Gallery last year. (The London Tates do not provide a break-down but tourists probably account for nearly half their visitors.) Post-Brexit, calls to charge foreign tourists entry may grow louder.

Nearly half of visitors to Margate go to see Turner Contemporary, researcher found. Photo courtesy Visit Thanet.

The report shows a bias against building new museums, advocating instead for the face-lift of existing spaces. New institutions should only be funded “where there is a demonstrable need,” it advises. Still, England lags behind France, which has FRACS, regional collections of contemporary art, or Germany, where most cities have a Kunsthaus and an art museum with a permanent collection.

But Mendoza acknowledges that new institutions have been among the great success stories of the past decade. The David Chipperfield-designed Hepworth Wakefield was awarded the 2017 Art Fund UK Museum of the Year award. Chipperfield’s Turner Contemporary is estimated to have attracted 48 percent more visitors coming to Margate especially to visit the gallery, which equates to 960,000 visits.

Turner Contemporary’s current shows include the first exhibition of Jean Arp’s work in a public gallery in the UK since the artist’s death in 1966. A collaboration with the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands, “Arp: The Poetry of Forms” is tonic for “remainers” (or remoaners, depending on your support of Brexit). Arp was a quintessential European, born in Strasbourg to a French mother and German father; he called himself “Jean” when speaking in French and “Hans” in German.