Art World

Getting a Master’s Degree in Curating Is All the Rage. But Is It Worth It?

We look at the new generation of curators to see if it's a requirement.

We look at the new generation of curators to see if it's a requirement.

Caroline Elbaor

As contemporary art becomes increasingly integrated into mainstream culture, so too does its vocabulary—in particular, the word “curate.” The term has been arguably hijacked in recent years: what once referred to a specific occupation in the arts now apparently applies to anything from artisanal coffee shops to online lifestyle blogs.

This phenomenon has helped bring curating and curators to the spotlight. Though it was originally an occupation that kept one behind the scenes, the appointment of curatorial posts is now fodder for news headlines, particularly when it comes to events like documenta or the Venice Biennale. More and more frequently, critics evaluate exhibitions based on how they are developed or formulated—thereby placing the responsibility of a show’s success directly upon the curator’s shoulders, and proving that they are no longer considered merely an overseer of collections or exhibitions.

As the position becomes more high-profile, the crop of those aspiring to be curators grows, with more universities offering specialized programs in the field.

It was not long ago that curating MAs were unheard of. Power players like Hans Ulrich Obrist, Jens Hoffman, Klaus Biesenbach, or Nancy Spector certainly did not need the backing of a degree in curatorial studies to make strides. But it is crucial to keep in mind that all of the curating programs are considerably young, and as such, the growing pressure to complete one is a fairly new development.

So we are left with the ultimate question: can one be taught to curate, and if so, is the degree worth it?

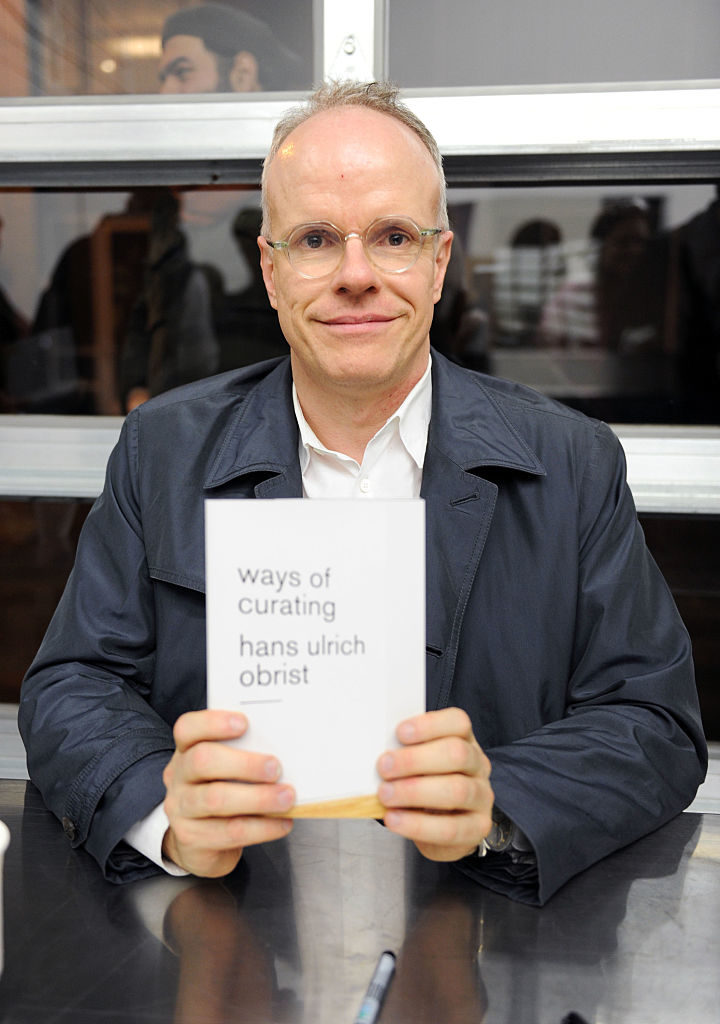

Hans Ulrich Obrist attends the Swiss Institute launch celebration of his new book Ways Of Curating on November 13, 2014 in New York City. Photo by Craig Barritt/Getty Images for Surface Magazine.

In his 2014 book, Curationism: How Curating Took Over the Art World and Everything Else, author and critic David Balzer explores the discipline’s rise in popularity. From the outset, Balzer’s skepticism of the profession is evident, and the book’s tone is dripping with doubt. It is therefore not surprising that, when it comes to the section about curating courses, he argues that curatorial Master’s programs are implicit in cheapening the word’s meaning, deeming them essentially worthless.

Balzer overlooks, however, the impressive list of alumni coming out of the top schools, particularly in London, where these programs are especially ubiquitous. The Royal College of Art (RCA)—which in 1992 was the first to implement a curating program—counts Stuart Comer, chief curator of media and performance art at MoMA in New York and 2014 curator of the Whitney Biennial, and Morgan Quaintance, last year’s Cubitt curatorial fellow, among its graduates.

Goldsmiths College, University of London. Photo via Goldsmiths College.

Jamie Stevens, curator at New York’s Artists Space, completed his Master’s at London’s Chelsea College of Art and Design; Goldsmiths College, another London institution, has educated the likes of Pavel Pyś, curator of visual arts at the Walker Art Center, and Hannah Gruy, artist and museum liaison at White Cube.

Meanwhile, Simon Castets, director and curator at New York’s Swiss Institute, holds an MA in curatorial studies from Columbia University; Ruba Katrib of the SculptureCenter attended the Bard Center for Curatorial Studies (CCS Bard) in Annandale-on-Hudson in New York; as did Cecilia Alemani, director of the High Line art initiative and curator of Frieze New York Projects, as well as curator of this year’s Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. And the list goes on.

Given this evidence, it makes a compelling case that at least some students are benefiting from these courses. Yet, what exactly students are shelling out money for remains ambiguous: is this serious academia, or a glorified networking affair?

The answer, of course, is usually both. But it is worth noting here that three high profile graduates, with important posts in the industry, chose not to be interviewed for this particular story so as not to burn bridges, either because they found issue with the idea of “teaching” curating or with the high cost of tuition. (A curator who wished not to disclose their identity commented: “I feel hugely ambivalent about these courses, especially in the American context where the fees just seem totally immoral to me.”)

Curating MAs tend to be two-year programs. On average, a program in the US will set one back roughly $40,000 per academic year. The UK operates a bit differently: fees vary depending on where you hail from. For instance, at the RCA, residents of the EU or UK pay £9,500 ($12,305) per year; this number jumps drastically to £28,400 ($36,785) for overseas students. And these high costs are only half of the concerns raised by MA doubters, who also seem to express an overall distrust of curriculums.

Ruba Katrib. ©Patrick McMullan. Photo by Nick Hunt/PatrickMcMullan.com

“Going to a graduate program for curating was in part figuring out what that was exactly,” said Ruba Katrib in conversation with artnet News. “I am not sure I got the answers I wanted then, but I think the program definitely prepared me to work in institutions, even though institutional methodologies were a very small part of the curriculum at the time.”

She went on to emphasize the importance of peer-to-peer support: “In my experience, the strength of the network has really been and continues to be in the students, who go off to work in various positions in various cities in the world. Perhaps more so than professors, guest critics, or other professionals who are brought in.”

Cecilia Alemani further supported this notion when discussing her experience. “Bard CCS was a groundbreaking experience for me―not only for what I have learned while studying there but most importantly for the people I met: colleagues, teachers, and visiting professors,” Alemani said.

As for the bottom line, she was enthusiastic about the degree’s value: “I met wonderful inspiring people I still collaborate with, and it provided me with a very strong academic foundation that I still use now in my curating.”

Alemani, in fact, makes up one half of a curatorial art world power couple: she is married to Massimiliano Gioni, who serves as chief curator and artistic director of the New Museum in New York City. (In a twist that proves just how small the art world is, Gioni’s longtime colleague, Lauren Cornell, left the museum recently for a directorship position at CCS Bard.)

Gioni is one of the lucky few who can list curating the Venice Biennale as an accomplishment (his turn was in 2013, when he was just 40 years old), and his organization of the 2010 Gwangju Biennial attracted over 500,000 visitors. But he never received a Master’s degree in the subject. “He is terribly well read without being academic,” Lisa Phillips, director of the New Museum, told the New York Times in 2013. “He sees curating as an art form.”

It is perhaps viewing the occupation as a kind of artistic practice that is the key to success. “Goldsmiths was absolutely fundamental to my career because it cemented for me the idea that curating is rooted in research and writing and the exchange of ideas with artists and peers,” Pavel Pyś told artnet News. “Goldsmiths was a chance to research, study, talk, think.”

Pavel Pyś. Photo courtesy the Walker Art Center.

Pyś also commented on the school’s ability to create a bridge between the curating students and those focused on studio art, citing artists he worked with at Goldsmiths who have gone on to enjoy major success, including Michael Dean, who was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2016, and Joey Holder.

When asked if his schooling was worth it, Pyś too had positive things to say about his alma mater: “Of course. I think it’s a really great program and I really valued my time … It offered a multi-perspective way of thinking about art.”

As for salary expectations, only those who skyrocket after their education receive healthy pay. A survey conducted by Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) reveals that chief curators make an average of $143,412 per year, while curatorial assistants flounder at a low salary of $42,458.

So, when all is said and done, is a Master’s degree in Curating worth it? In looking at those whose careers have flourished after graduating from these schools, one might conclude that receiving a Master’s degree in the subject is, in fact, an asset. All of the alumni spoken to agreed that regardless of any reservations they might have, the diploma was handy—mostly because of the doors it opened.

“I think the strength of the program is its community of alumni and teachers … Still now, over 10 years after I graduated, many of my classmates are people I work with professionally on a daily basis, and I know I can rely on this community for my professional development,” Alemani concluded of her time at CCS Bard.

So if you can make your way into a prestigious program, you could very well be surrounded by—and become yourself—the future generation of curators. Just beware of the hefty price tag.