Law & Politics

Italian Dealer Accused of Trafficking 2,000 Artifacts Wanted by U.S. Authorities

Edoardo Almagià's cousin and business partner also has ties to the Italian ministry of culture's disgraced former undersecretary, Vittorio Sgarbi.

Edoardo Almagià's cousin and business partner also has ties to the Italian ministry of culture's disgraced former undersecretary, Vittorio Sgarbi.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

The Manhattan District Attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit has obtained a warrant for the arrest of Italian dealer Edoardo Almagià, who is accused of selling thousands of looted antiquities worth tens of millions of dollars. He has been charged with conspiracy to defraud and possessing stolen property.

The unit has been investigating Almagià since 2018 and, so far, has seized 221 looted treasures worth nearly $6 million from major museums like the J. Paul Getty Museum, the MFA Boston, and the Cleveland Museum of Art. On this list is also the art museum at Almagià’s alma mater Princeton University, from which he graduated in 1973. Between 1984 and 2001, he sold the museum 14 antiquities, donated six, and lent another six. These 26 pieces had a combined valued of more than $450,000.

According to Italian law, antiquities belong to the state and the recovered objects have all been repatriated.

Interpol is expected to put out a red notice, an international request to law enforcement worldwide to co-operate in arresting Almagià. After this, Italian authorities would be able to detain him and extradite him to the U.S.

The unit’s 80-page warrant details the extent of Almagià’s alleged crimes. It is heavily informed by what it calls the “Green Book,” an incriminating ledger in which he documented the stolen goods that he was trafficking. It was taken from his possession by an informant who was in the middle of having it photocopied when they were allegedly assaulted by an angry Almagià who retrieved the Green Book. Despite this interruption, the informant managed to hold on to photocopies of several dozen pages that were turned over to law enforcement.

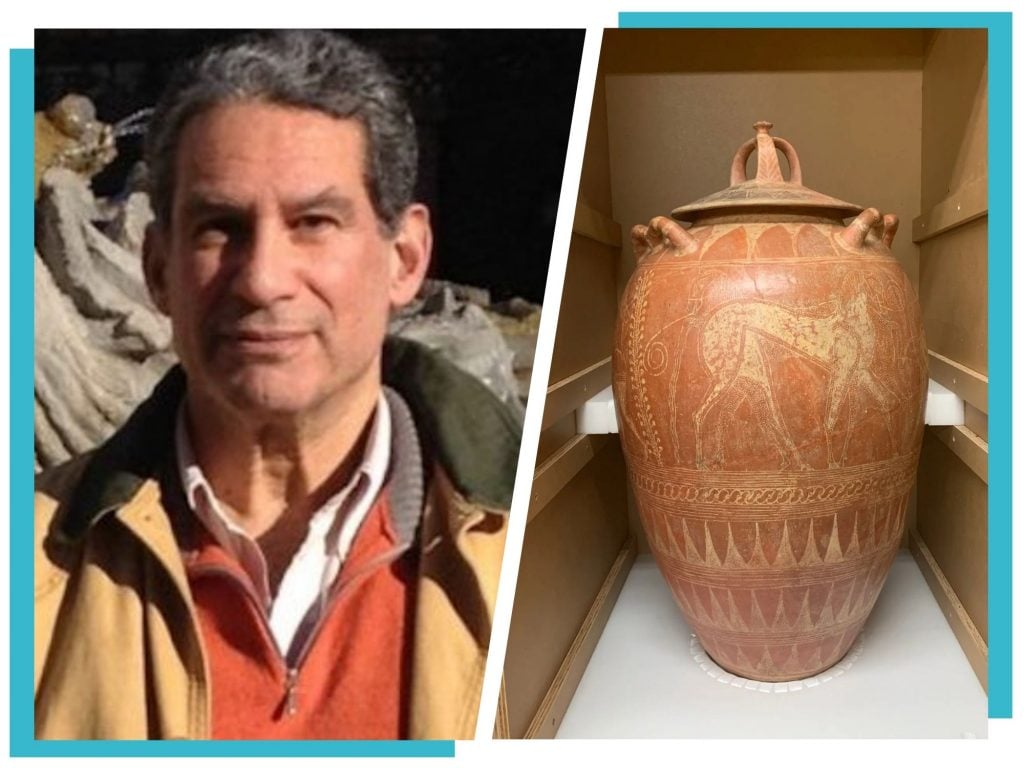

A collection of looted antiquities, some with ties to Edoardo Almagià, returned to Italy in a repatriation ceremony held in New York on August 8, 2023. Courtesy of the Italian Ministry of Culture.

According to a report in the New York Times, the informant who handed over photocopies of the Green Book was an ex-girlfriend of Almagià’s. Speaking to the newspaper, he denied violently attacking her. He also said of the charges against him: “I do not deny them but I do not accept them.” He later bemoaned the creation of dedicated crime units to investigate the trafficking of cultural goods, which he described as “scarlet letters and witch hunts.”

The rogue dealer would source his stock from a network of tomb raiders operating at archaeological sites in Italy, falsifying the necessary documents to export them to the U.S, according to an article in Princeton Alumni Weekly. The warrant claimed that Almagià operated his dealership out of apartments in Manhattan, legitimizing the illegally imported ancient treasures, which included Roman statues and Etruscan pottery, by lending them to established institutions for temporary exhibition before they were sold.

He has been on the radar of both U.S. and Italian authorities since the 1990s but, according to La Repubblica, previous investigations were scuppered by the statute of limitations.

In 2006, law enforcement got hold of the photocopied pages from the Green Book and Homeland Security searched Almagià’s apartment on the Upper East Side, causing him to flee to Italy. He managed to smuggle some antiquities with him but these were later seized by Italian authorities.

According to Il Sole 24 Ore, the warrant names Almagià’s cousin Peter Glidewell, a co-founder of the Madrid gallery Caylus, as a “business partner” who also profited from the sale of illicit goods. It is noted that he has ties to the Italian ministry of culture’s disgraced former undersecretary Vittorio Sgarbi, who had to step down this year after he was accused of possessing a stolen 17th-century painting.

The “complicit assistance” of a former curator at Princeton University Art Museum, Michael Padgett, was also described in the warrant. He apparently helped connect Almagià with institutional figures who would exhibit or acquire his looted goods. He has not currently been charged with any crimes and has denied any wrongdoing to the New York Times, noting that a previous accusation made in Italy in 2009 was eventually dismissed by an Italian judge in 2012.

In 2011, Princeton’s art museum voluntarily repatriated six items connected to Almagià but many other pieces have since been seized by the Manhattan D.A.’s unit, which was established in 2017, including six objects last April. In September, the Daily Princetonian admitted that there are 16 artifacts linked to Almagià still in its collection. The museum recently hired its first curator of provenance, who will be in charge of reviewing any contested items.