Art World

Art Bites: The Furor Over the Tate’s Acquisition of Carl Andre’s ‘Bricks’

The controversial Minimalist work led many a critic to lament the museum’s focus on abstract art.

When the Tate Britain opened its doors in August 1897, the institution, originally known as the National Gallery of British Art, quickly earned a reputation for being different from other museums. Instead of exhibiting work from canonized masters of the past, the Tate championed up-and-coming artists whose abstract and revolutionary styles clashed with that of their forebears.

“But,” as an National Archives article on the history of the museum noted, “the public has not always supported the Tate in its decision about the works of art added to its collection.” Visionary museum director Norman Reid received the biggest backlash yet when, in 1972, the Tate acquired Equivalent VIII, a collection of 120 firebricks arranged in a rectangular formation by the late Minimalist artist Carl Andre.

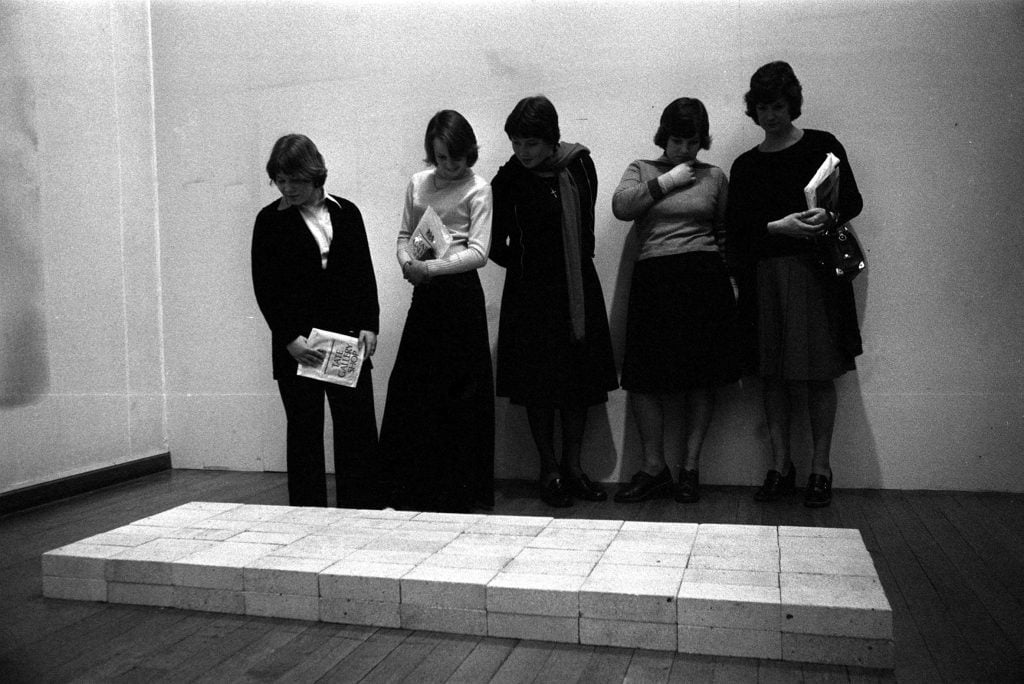

A man lies on the floor next to Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (1966) on view at the Tate Gallery in London, 1976. Photo: Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images.

During the following years, critics, visitors, and even dissenting museum staffers took to the press to argue that Andre’s installation pushed the definition of art too far. “They can’t make head or tail of them,” Arthur Payne, a gallery assistant, told the Evening Standard in 1976. “Whichever way you look at Britain’s latest work of art,” declared the Daily Mirror, “what a load of rubbish.”

Colin Simpson of the Sunday Times criticized the Tate for spending taxpayer dollars on a work that he and many others considered to be of little to no artistic value, insinuating that curators had been misled by Andre who, in the spirit of a grifter, arranged the bricks, “put a price tag of $12,000 on them,” and waited for customers.

Not all were angry with the museum, however. “The Trustees of the Tate have every right to spend a little on experimental art,” Hugh Jenkins, Britain’s Arts Minister, told the Daily Mail in response to the waves of criticism. “I do not question their judgement.”

Unfortunately for the museum, Jenkins was in the minority. “The ‘bricks’ scandal,” Tim Hilton mentioned in an obituary for Norman Reid, who passed away in 2007, “was not the controversy of a day or two.” Lasting for years, it not only prompted Reid to resign but also tarnished the Tate Britain’s image as a respectable institution.

Then again, Reid never cared much for prestige. During his directorship, he fought against admissions charges to ensure that exhibitions remained accessible for elites and laypeople alike. While he himself was more interested in traditional art, he encouraged his team of young curators to go out into the city, visit local galleries, and bring in original, iconoclastic work that challenged and rejected the prevailing tastes of the art world establishment.

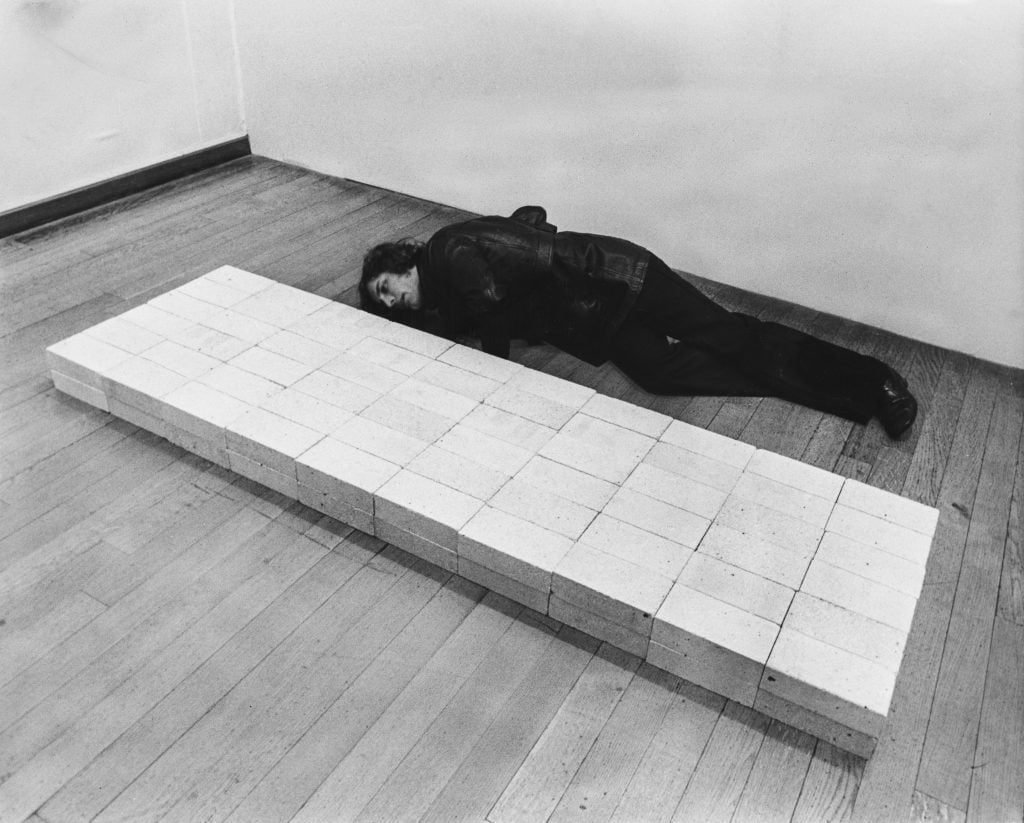

Carl Andre at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, 1978. Photo: Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

This was certainly true for Andre, whose minimalist and anti-representational art is heavily inspired by his upbringing in Puritanical New England. Just as the Puritans denounced the lavishly decorated sculptures and paintings sponsored by the Catholic Church following the Reformation, so do Andre’s bricks reject the representational, ornamental style of previous art movements.

Ironically, the flood of negative reviews sent many a visitor on their way to the Tate to see Equivalent VIII for themselves. One of these, a chef named Peter Stowell-Phillips, defaced the installation by covering the white bricks with blue food dye to protest against what he felt was the museum’s misuse of taxpayers’ money. After a quick wash, Equivalent VIII was put back on display.

Andre himself was unfazed by the scandal that followed his bricks.

“Bad publicity is as good as good publicity,” he reflected in 2014 of the controversy. “If they say [the work is] nice and that’s all, it’s no good. If they go on for hours and hours saying how terrible it is, then it’s good.”

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.