People

Carl Andre, the Minimalism Pioneer Who Sculpted With a Stark Line, Has Died

The artist was 88.

The artist was 88.

Min Chen &

Guelda Voien

Carl Andre, sculptor and master of the minimalist line, died January 24, at age 88. His passing was announced by his gallery, Paula Cooper, which has represented the artist since 1978.

“Carl Andre redefined the parameters of sculpture and poetry through his use of unaltered industrial materials and innovative approach to language,” the gallery said in a statement. “He created over 2,000 sculptures and an equal number of poems throughout his almost 70-year career, guided by a commitment to pure matter in lucid geometric arrangements.”

Andre’s inquiries into geometry, horizontality, and materiality, which he began in the mid-1960s alongside peers such as Frank Stella and Donald Judd, would help form the foundations of Minimalism. His sculptures and installations, variously crafted out of bricks, copper, wood, and even Styrofoam, stripped structures down to their barest forms. With their often flat orientations, they challenged viewers’ relationship to sculpted work, daring to suggest movement.

“My idea of a piece of sculpture is a road,” he once told art historian Phyllis Tuchman. “Most of my works—certainly the successful ones—have been ones that are in a way causeways—they cause you to make your way along them or around them or to move the spectator over them. They’re like roads, but certainly not fixed-point vistas.”

Yet, the artist’s legacy remains a troubled one, particularly following the sudden death of his wife—artist, photographer, and filmmaker Ana Mendieta. The curious circumstances surrounding her passing may have seen Andre tried and acquitted of homicide, but his alleged role in her death has continued to build over nearly four decades.

Carl Andre, Breda (1986), installed at the International Exhibition of Contemporary Art in Paris, France, 2010. Photo: Jean-Marc Zaorski/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

Born in 1935 in Quincy, Massachusetts, Andre graduated from Phillips Academy in Andover, where he roomed with future filmmaker and photographer Hollis Frampton. Among his instructors, Andre named Abstract Expressionist Maud Morgan and her husband as his favorites, as they were “up on the latest trends.” Through Frampton, Andre would also become acquainted with a young Frank Stella.

After serving for a spell in the U.S. Army, Andre moved to New York in 1956, sharing an apartment with Frampton on Mulberry Street and a studio with Stella at the corner of West Broadway and Broome Street.

It was at the downtown loft that Andre would commence sculptural practice, inspired by Stella’s black paintings as much as by the work of Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi. His early wooden sculpture series Ladders and Pyramids bore out his geometric obsession and rejection of the “idealized surface.” While making art and writing his concrete poetry, he worked as a freight brakeman for the Pennsylvania Railroad in New Jersey, a job that would shape his evolution as much as his uniform of overalls.

Carl Andre, Untitled (Element Series) (1960). Photo: Geoffrey Clements / Getty Images. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

Andre opened his first solo show, “Shape and Structure” at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, for which he garnered immediate acclaim. From there, his work would only grow more austere and horizontal in his bid to reorient how the spectator experienced his sculptures. Cases in point: 1966’s Lever, Andre’s name-making floor-bound sculpture made up of 137 bricks in a straight line, which cleaved whatever space it was installed in; and 1967’s Eight Cuts, a field of concrete blocks with eight holes or “cuts” that exposed the floor underneath, which viewers were invited to traverse.

“You can stand in the middle of [the work] and you can look straight out and you can’t see that piece of sculpture at all,” he once said, “because the limit of your peripheral downward vision is beyond the edge of the sculpture.”

Andre would go on to show in landmark exhibitions from “Primary Structures” at New York’s Jewish Museum in 1966 to Documenta 4 in Kassel, Germany in 1968. By 1970, the Guggenheim Museum was staging the first retrospective of his work. The acquisition of his 120-brick sculpture, Equivalent VIII (1966), by the Tate Gallery in London would cause significant uproar when it was put on view in 1976, with at least one publication deeming it “a load of rubbish.”

As his star rose, Andre would also grow associated with the Art Workers’ Coalition, a New York-based organization that lobbied the city’s galleries for improved artists’ rights, as well as an end to oppression in the art world.

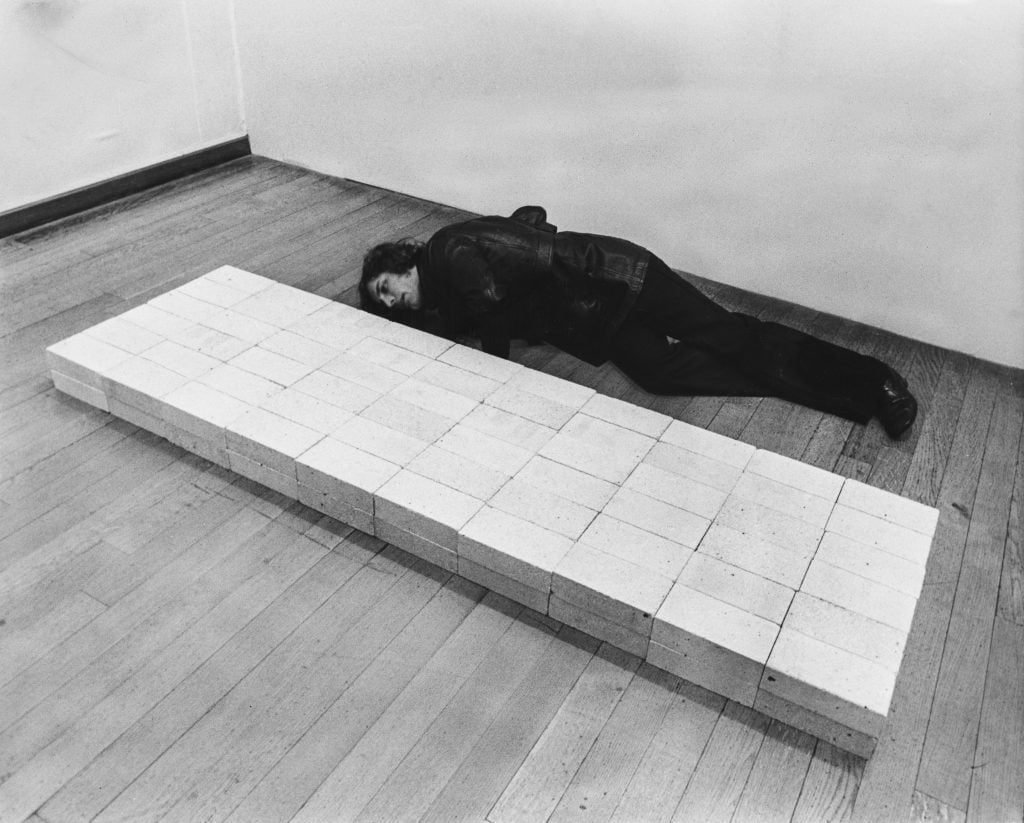

A man lies on the floor alongside Carl Andre’s sculpture Equivalent VIII (1966) at the Tate Gallery, London, 1976. Photo: Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images.

In 1979, Andre met Mendieta, who had fled Cuba for the U.S. at a young age and in subsequent years, developed her rich “earth-body” practice. A mere nine months after they wed in 1985, Mendieta fell out the window of their 34th-floor Manhattan apartment to her death. What was cast as an accident by Andre and many of his art world friends was a suspected homicide to others, especially as Mendieta’s fall had followed a quarrel that left scratches on Andre’s face.

Andre was indicted and eventually acquitted of second-degree murder after forgoing a jury trial in 1988. Stella supposedly offered a prize racehorse as collateral to secure the sculptor’s bail.

Anger surrounding the fact that Andre walked free from the alleged crime has only grown in recent years. Mendieta’s supporters have protested the opening of “Carl Andre: Sculpture as Place, 1958–2010” at Dia:Beacon in New York in 2014 and at the Museum of Contemporary Art, L.A. in 2017. At the former, they bloodied the pavement outside the institution, and at the latter, waved signs that read “¿Dónde está Ana Mendieta?” (“Where is Ana Mendieta?”).

The WHEREISANAMENDIETA Collective protest the 2016 opening of the Tate Modern extension, which featured Carl Andre’s works. Photo courtesy of the WHEREISANAMENDIETA Collective.

In 2020, actress Ellen Barkin accused Andre of violently assaulting her at a party when she was 22 in a tweet that also referenced the circumstances of Mendieta’s death. The 2022 audio series The Death of an Artist, hosted by curator Helen Molesworth, further interrogated Mendieta’s death, Andre’s alleged part in it, and the shocking silence that followed her demise.

Meanwhile, Andre’s work is in the collections of several museums around the world—from New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Washington D.C.’s National Gallery of Art to Paris’s Centre Pompidou and London’s Tate Modern.

In 2022, the artist presented his final large-scale sculpture at Paula Cooper. Titled 5VCEDAR5H (2021), it featured 10 red cedar blocks arranged alternately upright and on their side against a white wall. As always, they emerged from Andre’s fascination with mass and material, while offering a rare vertical gesture.

Andre is survived by his fourth wife, artist Melissa Kretschmer, and a sister, Carol.

More Trending Stories:

A Case for Enjoying ‘The Curse,’ Showtime’s Absurdist Take on Art and Media

Artist Ryan Trecartin Built His Career on the Internet. Now, He’s Decided It’s Pretty Boring

I Make Art With A.I. Here’s Why All Artists Need to Stop Worrying and Embrace the Technology

Sotheby’s Exec Paints an Ugly Picture of Yves Bouvier’s Deceptions in Ongoing Rybolovlev Trial

Loie Hollowell’s New Move From Abstraction to Realism Is Not a One-Way Journey