Art World

Art Bites: Why Chris Burden Asked a Friend to Shoot Him

The artist is known for punishing performance pieces, and none of them topped this one.

The artist is known for punishing performance pieces, and none of them topped this one.

Vittoria Benzine

What would you do for art? The Los Angeles-based performance artist Chris Burden famously got shot for the cause.

Burden’s Shoot (1971) was a shocking performance captured on Super 8 film. While this work, and Burden’s ensuing oeuvre, fueled the body art movement and inspired artists like Marina Abramović, the drama of Shoot itself partly resulted from a marksmanship mishap.

Burden, born in 1946, grew up gallivanting between Boston, France, and Italy. As one 2016 documentary emphasized, he felt he didn’t arrive at performance, but was born with it. As the story goes, Burden developed an interest in art while recovering from emergency surgery without anesthesia after a Vespa accident on Elba shattered his left foot.

He earned a bachelor’s in visual arts, physics, and architecture at Pomona College in 1969, then an MFA from the University of California, Irvine in 1971. There, Burden became the talk of the campus by cramming himself into a locker for five days straight, with only drinking water piped in from a locker above and a makeshift toilet in the one immediately below.

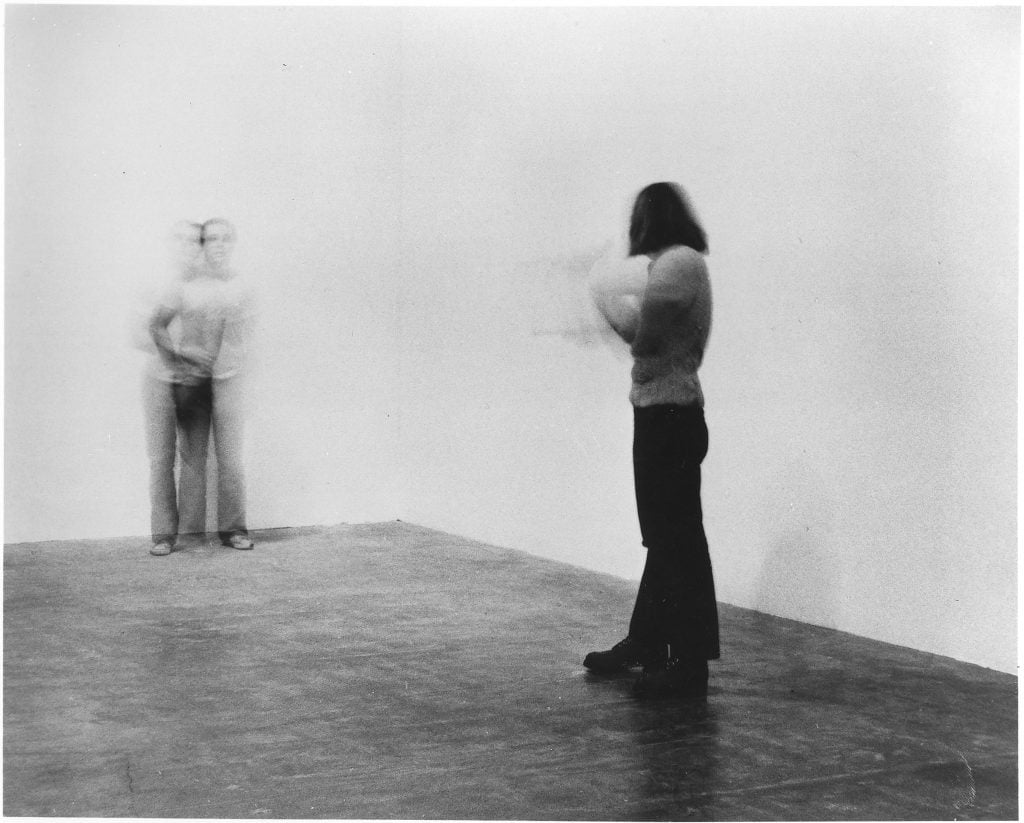

Chris Burden, Shoot (1971) © 2024 Chris Burden/Licensed by the Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Gagosian.

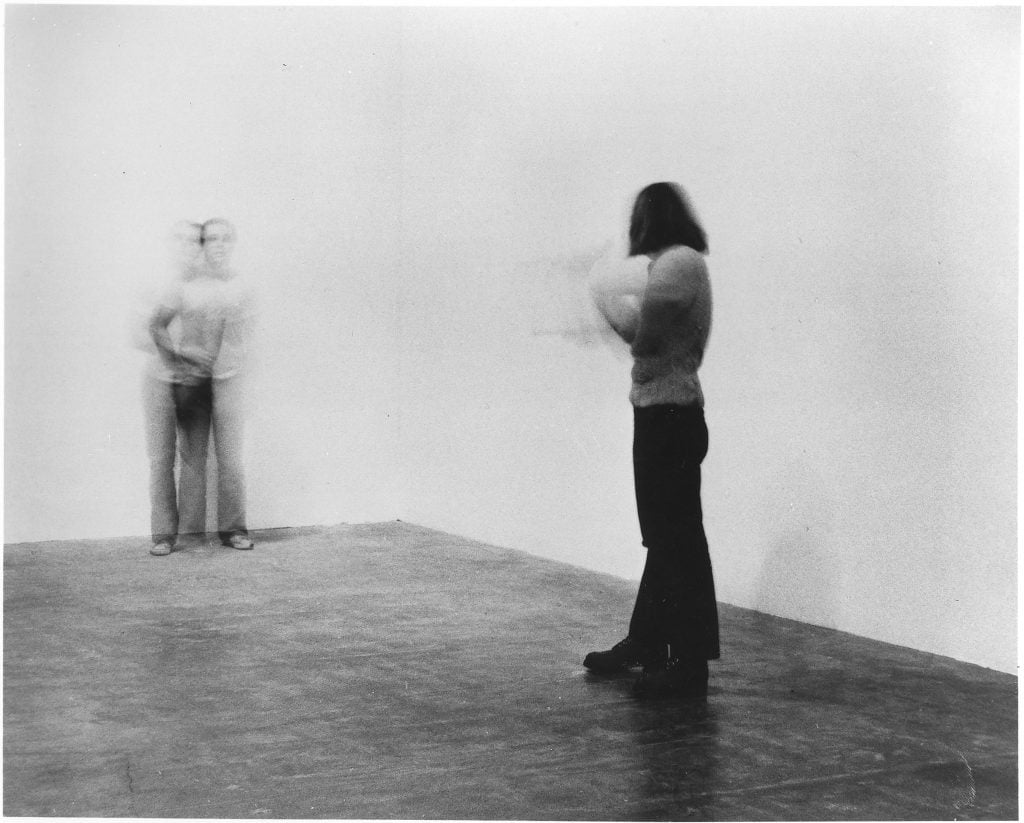

At 7:45 p.m. on November 19, 1971, Burden staged Shoot at F-Space Gallery, which he and several MFA students, including performance artist Barbara T. Smith, opened in industrial Santa Ana. Twelve friends bore witness in the locked space. Burden recruited his buddy Brice Dunlap to don a matching austere outfit, stand 15 feet away, and shoot at him with a .22 caliber rifle.

In the first half of Burden’s career, before he transitioned to maximalist sculptures (one of them now a certified selfie spot), his stunts were scathingly political. This one highlighted the cultural proliferation of guns in America and the savagery of the Vietnam War. After all, everyone in the crowd saw what was happening, and no one stopped it. Then again, interference could have rendered the performance fatal.

“It’s as American as apple pie,” Burden once said, “either being shot or shooting people.” Still, few actually know what it feels like.

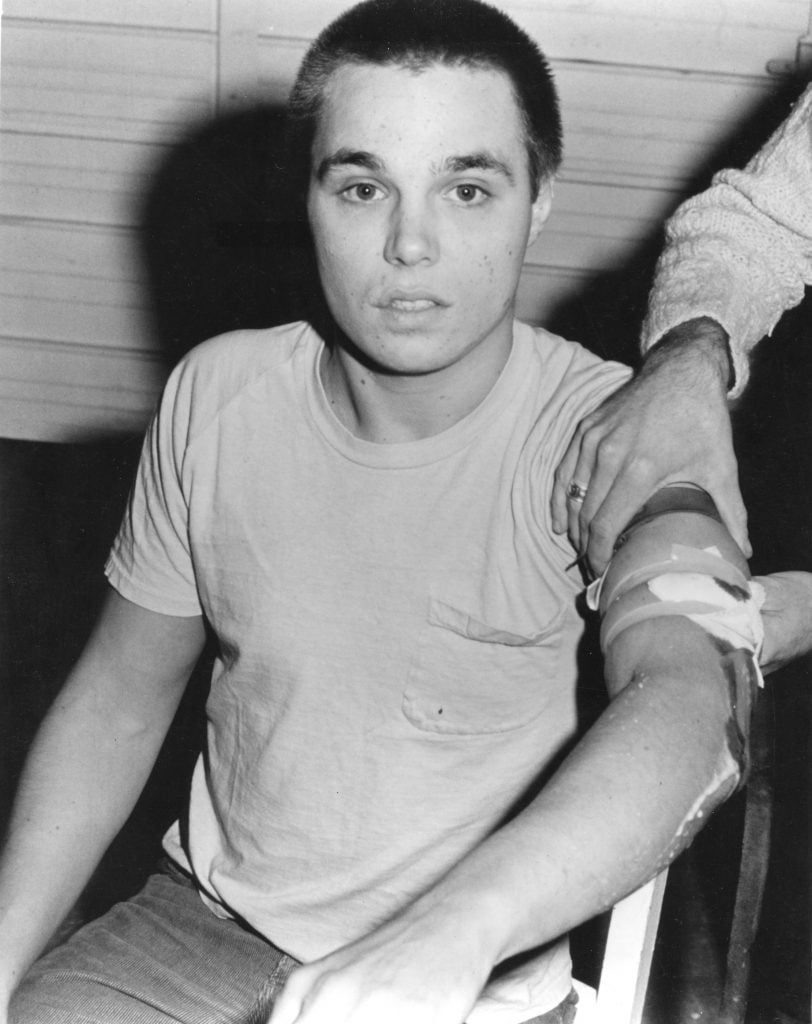

Dunlap was only supposed to graze Burden’s arm, but as he recalled in Burden’s biopic, “I guess I pulled a little bit to the left.” The bullet went straight through Burden’s arm, and in 1973, he told the New York Times that the impact “felt like a truck hit my arm at 80 m.p.h.” In the footage, Burden exits stage right with relative composure. It all took eight seconds. “Everyone then had to deal with the reality that he had, in fact, just been shot,” Smith told LAist. At the hospital, they devised a fake story.

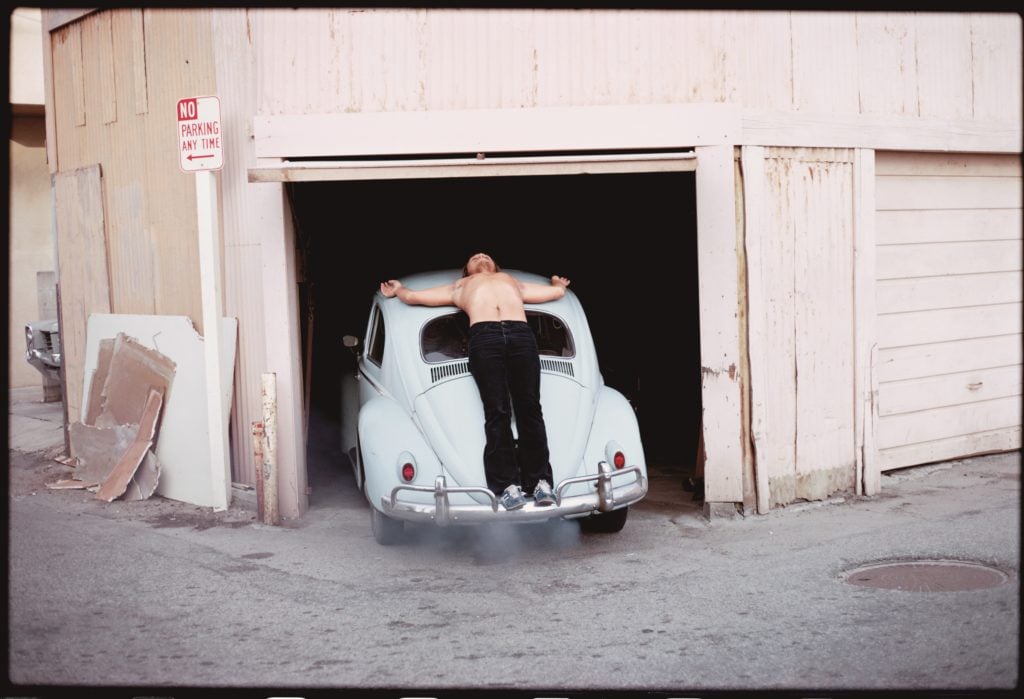

A still from the documentary Burden (2016), showing the artist performing Trans-Fixed (1972). Courtesy Magnolia Pictures. © 2019 Chris Burden / licensed by The Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Shoot sparked controversy—and made Burden a sensation. He notified the avant-garde publication Avalanche about the performance ahead of time. A local journalist covered it for an L.A. tabloid. The news even got picked up by Esquire. Underground radio stations started calling Burden, asking when his next stunt would be. He attained the lifelong, reductive label of “masochist,” only heightened by the outlandish, problematic escapades that followed.

Most famously, Burden crucified himself on a VW Bug for Trans-Fixed (1972), and writhed atop glass in Through The Night Softly (1973). He became the first artist to be represented by Gagosian gallery in 1978, but continued questioning art’s commodification with works like Doomed (1975) and Diamonds are Forever (1981).

For all their buzz, though, none produced the quite same effect as the shot heard around the art world.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.