Art History

A Manet Painting Was Divided for Years—Until Degas Brought It Back Together

"The Execution of Maximilian" was chopped up into four parts after Manet's death.

"The Execution of Maximilian" was chopped up into four parts after Manet's death.

Richard Whiddington

Édouard Manet was not immune to bad press. In 1864, a year on from scandalizing Parisian mores with his vision of bourgeoisie vice in Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (1863), his follow-up Salon entry was being savaged by critics. This time, the composition rather than the content was at fault. And so, one afternoon, Manet took a pocketknife to An Incident in the Bullring (1864) and separated the dead bullfighter from his lively surroundings.

It was a restless habit, one Manet practiced throughout his career, cutting away gypsies from their countryside, nymphs from their paradise, young aristocrats from their chambers. Nor were the paintings of other artists off-limits. He once slashed an intimate double portrait of himself and his wife, Suzanne, that Edgar Degas had gifted to the Manets in exchange for a still life.

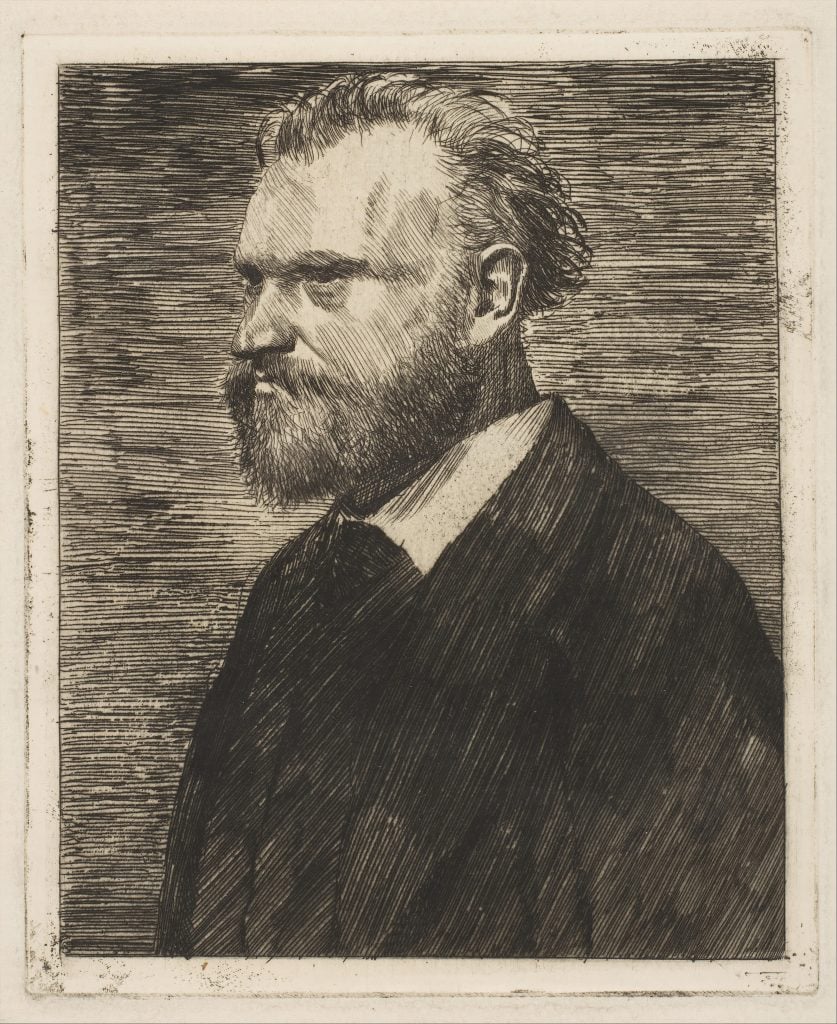

Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet, Bust-Length Portrait (1864–65). Photo: Heritage Art / Heritage Images via Getty Images.

Manet and Degas were almost exact contemporaries and had found fast friendship as the rebellious sons of bourgeois families keen to find a new way for art. But when Degas discovered his portrait had been defiled—allegedly, Manet thought Suzanne’s face was mispainted—he snatched the work from the wall and huffed off home. There, he dispatched a note that read: “Monsieur, I am returning your Plums” in reference to a still life that had been gifted to him.

The friendship fractured, never quite recovering, though it didn’t stop Degas performing an act of kindness for Manet after his death in 1883. This concerned reassembling The Execution of Maximilian (1867), a painting of the Mexican emperor who had been killed by nationalists that year.

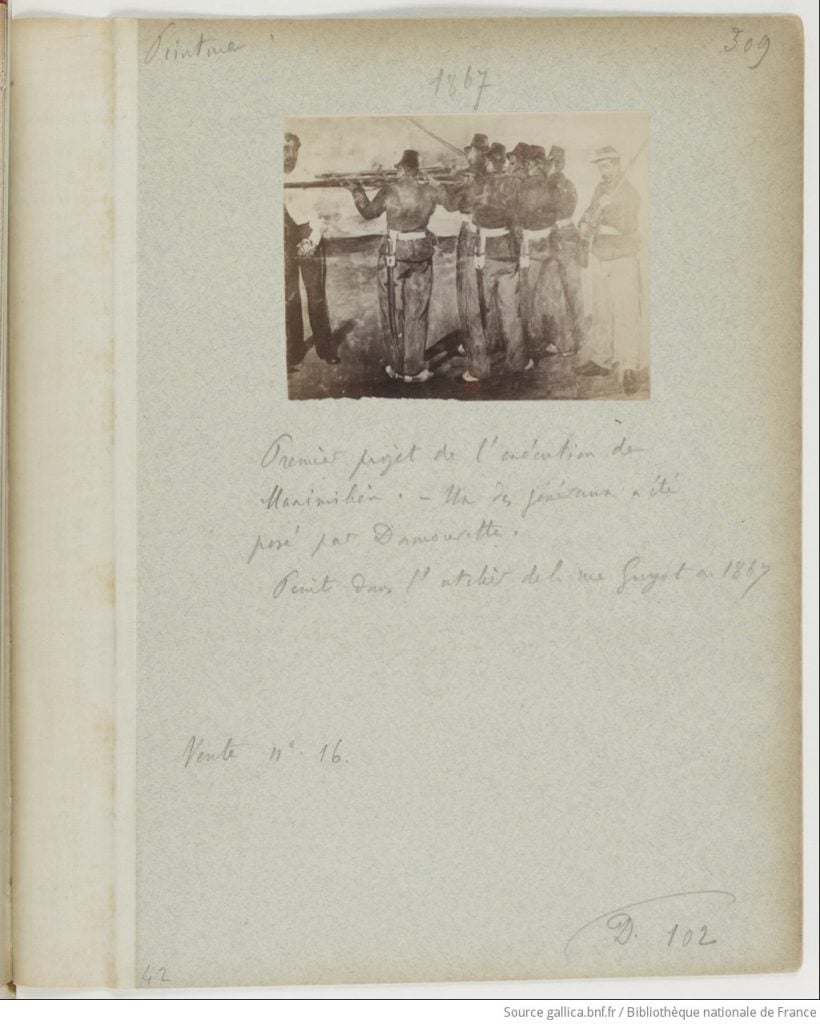

The grisly story, which arrived in a slow drip of newspaper reports, reflected poorly on Napoleon III, who had installed the emperor as a puppet only to withdraw military support. Manet was fascinated and, perhaps sensing his Goya moment, made at least four attempts to paint it (the first is pictured below). For obvious reasons, depicting the gross diplomatic failure of France’s ruling emperor was politically sensitive and in 1868, midway through his second attempt, Manet gave up and bundled it away at Suzanne’s family house.

Édouard Manet, Execution of Maximilian (1867). Photo: Barney Burstein/ Corbis/ VCG via Getty Images.

When Manet revisited the painting a decade later, he found it damaged. The left-hand side of the canvas was cut away, disappearing Maximilian and one of his generals. Scholars are unsure if it happened by Manet’s hand, but given his proclivity for canvas cutting, it seems likely. When the artist died in 1883, his family sliced the painting up into four and sold off the parts.

This chronology is made clear by the work of Fernand Lochard, who was commissioned to photograph all the works in Manet’s studio for the auction of his estate (four thick albums, 88 photos each). In Lochard’s photograph, the painting remains intact. The family would later cut away two pairs of legs: those of a Mexican general and those of the sergeant loading his gun.

The Fernand Lochard photograph of The Execution of Maximilian. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Degas was outraged when he learned The Execution of Maximilian had been cut up by Manet’s family. “All I can say is never marry,” he allegedly noted to an art dealer. Degas hunted down the pieces and in time reassembled the painting. First came the sergeant loading his rifle, then the firing squad, last the two fragments of Maximilian’s general. Alas, neither the legs nor the left-hand side of the painting have ever been found.

He glued these onto a specially-prepared canvas, offering space (and hope) for the missing parts. When London’s National Gallery acquired the work in 1917, it undid Degas’s meticulous handiwork and would display the fragments separately, if at all, for nearly 80 years. Today, The Execution of Maximilian is whole again—well, sort of.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.