Archaeology & History

This Mysterious Pyramid Dominated a Prehistoric Mexican City—and Still Guards Its Secrets

The pre-Columbian city of El Tajín is thought to have been built by an indigenous people whose culture predated the Aztecs.

In 1785, a Spanish official named Don Diego Ruiz was looking for illegal tobacco plantations in the Papantla region of Mexico (then called New Spain), near the modern-day city of Veracruz, when he stumbled upon a partially buried, 60-foot-tall pre-Columbian pyramid. After making a sketch of the structure, Ruiz reported his find to Gaceta de Mexico, a colonial newspaper, setting in motion a lengthy excavation process.

Fast forward two centuries, and the Pyramid of the Niches, as it is now known, has become one of the most impressive archaeological sites in all of Mexico, a country filled to the brim with Aztec and Toltec architecture. The Pyramid of the Niches wasn’t made by either of these two well-known pre-Columbian civilizations, though. Instead, archaeologists believe it was erected by the Totonac or Huastec peoples, indigenous groups that predate their better-known successors.

Excavations proved that the Pyramid of the Niches wasn’t a lone structure, but part of a greater settlement called El Tajín, after a pantheon of Totonac rain gods who, according to local legend, moved into the city after it was abandoned around 1150 C.E., when the Medieval Warm Period saw floors in the surrounding area. Construction of El Tajín is thought to have started around the year 600, with the city expanding to cover a total of 146 acres. The Pyramid of the Niches, meanwhile, is thought to have been built between 600 and 1100 C.E., smack in the middle of El Tajín’s heyday.

View of Tajín Viejo site. Photo: Eye Ubiquitous/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

The ruins of El Tajín paint a picture of a powerful polis. In between periods of urban expansion, its government waged war on and conquered numerous surrounding settlements, extending the size of its dominion. Sculptural reliefs, meanwhile, offer a vague impression of the culture’s cosmology, which revolved around the duality between Tajín, the rain god, and Quetzalcoatl, the sun god, who kept both the human and natural world in harmony.

Architectural features suggest El Tajín may have been divided into two districts: an older, southern district and a newer, northern one now referred to as Tajín Chico. Tajín Chico was built on a raised plateau, with its buildings placed along a single axis. The reason for this feat of urban planning is unknown, though it surely must have been a deliberate decision, as it ensured all of the newer buildings faced the older parts of the settlement at a 60 degree angle.

The Pyramid of the Niches at El Tajín. Photo: DeAgostini/Getty Images.

The Pyramid of the Niches—Pirámide de los Nichos in Spanish—owes its name to the 365 symmetrically arranged niches carved into its exterior, an unusual feature that sets it apart from other pre-Columbian pyramid structures in Mexico. As with the placement of the buildings in Tajín Chico, this seems to have been a deliberate architectural choice, as the sun’s movement casts ever-changing, perhaps cosmologically significant patterns of light and shadow.

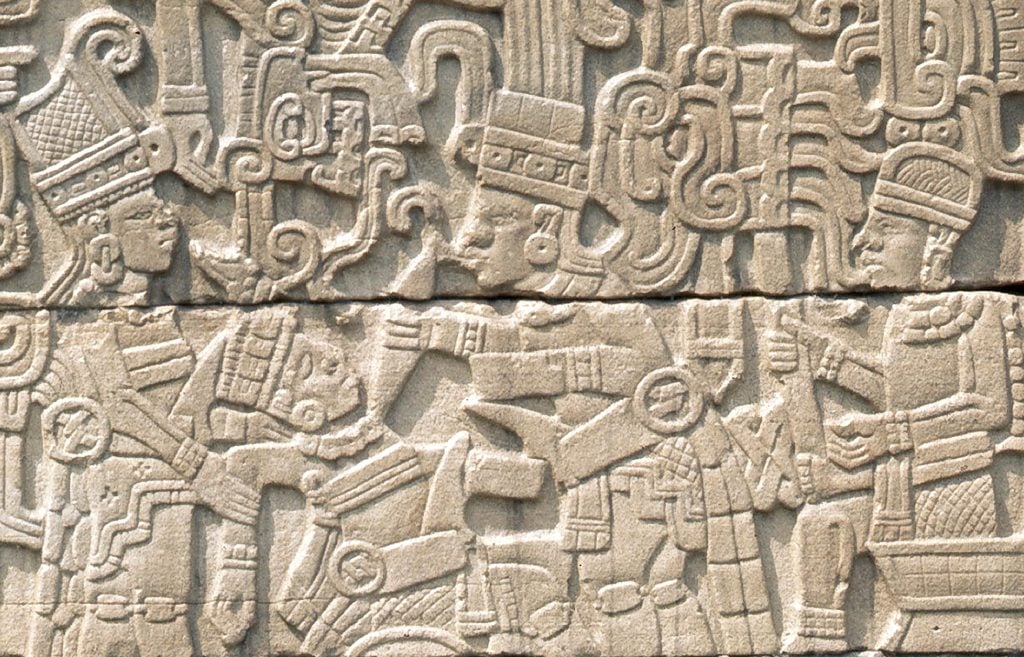

Both inside and outside, the pyramid is covered in reliefs, some of which were originally painted red, featuring designs similar to those seen in some Maya temples.

Other noteworthy structures in El Tajín include a collection of 21 ballgame courts—some of which are believed, based on reliefs engraved into their surrounding walls, to have been used for competitive games, others for political disputes or divine invocation. El Tajín is hardly the only pre-Columbian settlement to feature such courts; similar ones have been found all over Central and South America, including the ancient Maya city of Tikal in northern Guatemala. The large number of courts at El Tajín suggests the city may have hosted competitions for players from other settlements.

Relief from the south ball court at El Tajín, depicting the sacrifice of a ball player. Photo: Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images.

Unlike other archaeological sites in Mexico, which are currently being reburied due to cuts in government funding, El Tajín continues to be the focus of numerous research projects. In 2022, archaeologists associated with Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History used LiDAR (laser imaging, detection, and ranging) technology to scan for structures hidden underground, finding several hitherto unknown entrances to the city, shedding light on its flooding and subsequent abandonment.

Sometimes, archaeology gets big. In Huge! we delve deep into the world’s largest, towering, most epic monuments. Who built them? How did they get there? Why so big?