Art World

Art Bites: How the Met Got Its Ancient Egyptian Temple

Winning the temple was game of art, money, and politics.

The Nile has forever been Egypt’s boon and its bane. In the 1950s, the country sought to control the river’s flooding by building the Aswan High Dam, an architectural wonder hailed as a modern pyramid.

Desert would become farmland and hydroelectric turbines would provide power for millions. There was a problem: a resulting 300-mile lake would submerge five ancient Nubian temples and Egypt didn’t have the funds to relocate them.

UNESCO organized an international fundraising campaign and the U.S.—with a healthy shove from Jacqueline Kennedy—committed to contributing $16 million. In 1965, Egypt gifted the Temple of Dendur as a token of gratitude. The question was, which American city was fit to house a 2,000-year-old sandstone temple?

There were plenty of takers. Miami, Memphis, Philadelphia, Baltimore, a town in Illinois called Cairo, and a dozen others expressed interest, a jostling media dubbed “The Dendur Derby.” Two favorites soon emerged: New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Washington, D.C.’s Smithsonian Institution.

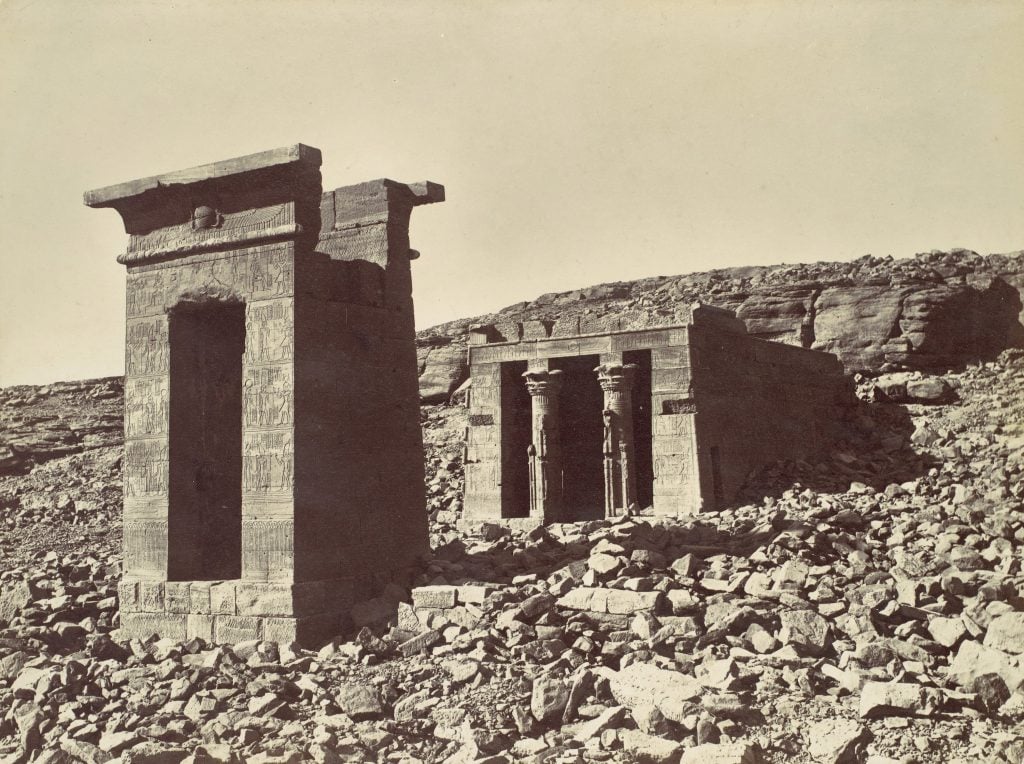

Photograph of the Temple of Dendur from 1870. Photo: Felix Bonfils/Getty Images.

In tone and approach, the institutions were diametrically opposed. Under the leadership of charismatic director, Thomas Hoving, the Met campaigned bombastically, proposing a dazzling new wing for the temple. By contrast, his counterpart at the Smithsonian, S. Dillon Ripley, remained understated and suggested a naturalistic outdoor setting. The Met critiqued this laissez-faire approach, arguing the harsh climate would quickly render the temple a pile of sand.

The Johnson administration agreed and, in 1968, the 661 crates containing the disassembled temple arrived at the museum. Short of space, they were kept in a parking lot.

The Temple of Dendur was stored in the Met’s parking lot before being reconstructed. Photo: courtesy the Met.

Hoving had won the fight for the temple, but a battle to reconstruct it awaited. His vision was a lofty thing of steel, water, and glass, one the former Parks Commissioner pushed into Central Park. Conservationists howled. Rallies were held. Then, in October 1973, Egypt invaded Israel. Suddenly, bankrolling the glorification of an Egyptian temple was considerably less appealing to New York philanthropists.

One individual dissuaded neither by politics nor the considerable funds being requested was Arthur M. Sackler. He’d forged (ahem, bought) a strong connection with the museum under Hoving’s predecessor, James Rorimer, and now made his largest donation to date, $3.5 million. The protracted nature of the agreement, however, meant the Met remained short of funds and the city provided more than $1 million.

Crowds inside “Treasures Of Tutankhamun Exhibition” exhibition. Photo: Getty Images.

By 1974, construction on the Sackler Wing was under way, with Italian stonemasons called in to reassemble the first century B.C.E temple according to grooves and markings on the stones. The Temple of Dendur opened to the public in 1978, accompanied by “Treasures of Tutankhamun,” widely considered the first museum blockbuster show. Skeptics were vanquished and the legacies of both director and donor were settled.

The Smithsonian would have its revenge. For a decade, Sackler had secretly stored his collection rent-free at the Met, a 600-square-foot space known as the “Sackler enclave.” The museum assumed such accommodations prefaced a generous gift. The relationship, however, had soured. Sackler found the director that arrived in 1977, Philippe de Montebello, inadequately deferential and was aggrieved by the museum renting the temple out for private parties.

When news of the Sackler enclave broke, prompting the Attorney General to investigate, the Met assumed it would hasten the gift. Not so. Ripley swooped, dangling the prospect of a Sackler Museum on the National Mall. Sackler took the bait. Soon, curators from the Smithsonian arrived in New York, picked out the finest 1,000 items, and carted them back to Washington, D.C.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.