People

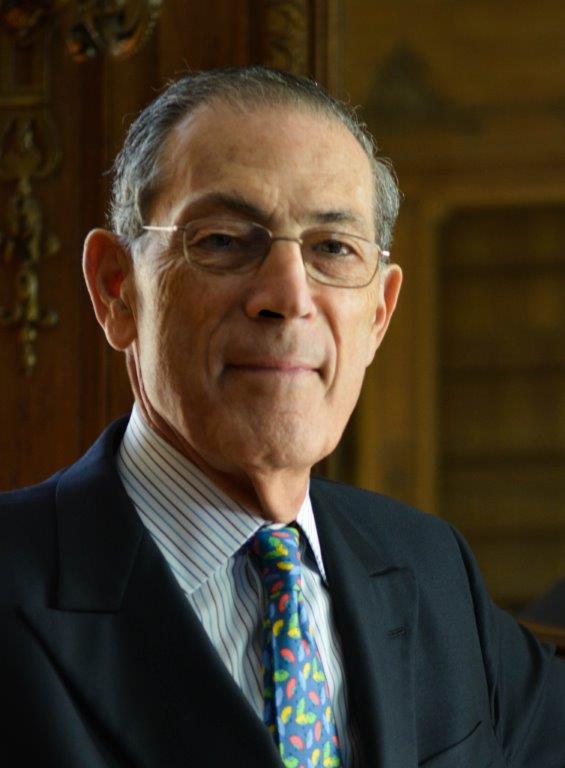

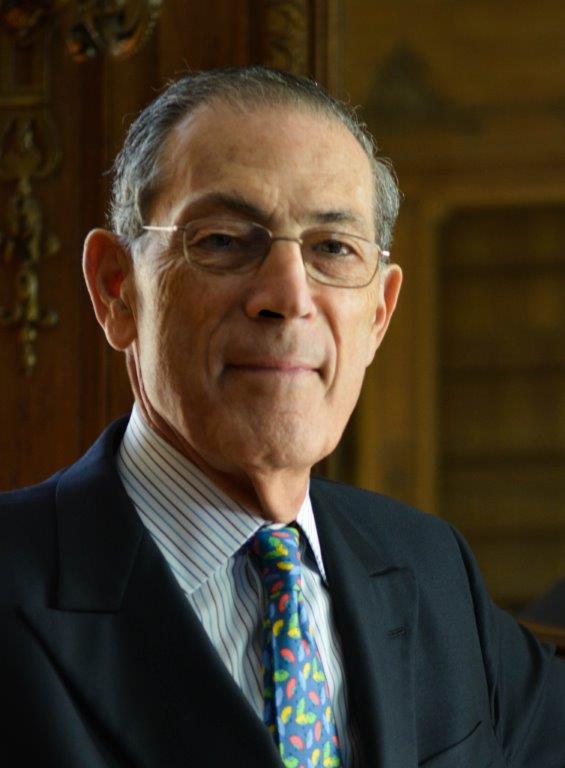

Philippe de Montebello on How the Metropolitan Museum of Art Can Reclaim Its Glory

The former Met director also discusses his new job at Acquavella.

The former Met director also discusses his new job at Acquavella.

Andrew Goldstein

A grandee in the annals of American museum history, Philippe de Montebello is, at 81, an institution in his own right—as venerable and encyclopedic as would befit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which he led for three decades.

Born Count Guy Philippe Henri Lannes de Montebello to a long line descended from the Napoleonic aristocracy, he celebrated his first job at the Met, as a curatorial assistant in 1963, by commissioning a supply of business cards from Cartier. In 1977, he ascended to the directorship, succeeding the freewheeling Thomas Hoving. Even though he retired in 2008, his name remains synonymous with the museum.

Now the chairman of the Hispanic Society Museum & Library, which he is leading through a multiyear renovation, de Montebello has been watching the recent turmoil at the Met—culminating in the ouster of director Thomas Campbell in February, and the ascension of Daniel Weiss as both interim director and president and CEO—with barely contained exasperation. Led astray by Campbell’s headlong embrace of the digital and contemporary art, the Met, de Montebello feels, is in need of a renaissance, and a return to its greatest strength: its collections.

De Montebello himself, however, is not afraid to try something new, and last week it was announced that he would be joining Acquavella Galleries as the latest prominent museum figure to venture into the commercial sector.

Recently, artnet News’s editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein sat down with de Montebello to discuss the changes—and opportunities—at the Met, and his new role in the gallery world. (This is the second installment of a two-part interview.)

As the chairman of the Hispanic Society of America, you are charged with updating a historical museum to attract today’s audiences and also raising money to fund an ambitious renovation of its home. These challenges, of course, pale in comparison to those currently faced by your old employer, the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This February, Thomas Campbell stepped down as director amid vocal concern about the museum’s finances in the face of a planned $600 million renovation to create new space for contemporary art, as well as more private concerns about his management style. What did you make of this shakeup?

I think that it is long overdue. It has been a difficult period for the museum, one in which a lot of very good people have suffered and left involuntarily. At the same time, the fundamental aspects of the Met have not changed. The Met will always remain the greatest museum in the world. It has continued to do wonderful exhibitions. It is encyclopedic, and it continues to show its collections beautifully. I have no issue with that.

It’s more the attitudinal shift. The messages that are sent out have a completely unbalanced emphasis on contemporary art, as if somehow the crowds that come to the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth Avenue—where people go to see Egyptian, Greek, and Islamic Art and great European paintings—are suddenly going to come to see contemporary art. This when there are a thousand commercial galleries all over New York, and how many museums with contemporary art? It’s nonsense.

So, the Met is very lucky right now to have an individual, Dan Weiss, who they have made the paid president—as opposed to president of the board—and CEO of the museum. Now, Tom Campbell was both the director and the CEO before he departed. In the abstract, I would say that it is not right to split these roles between two people. The person who has the vision, the passion, and the knowledge about museums and about art is the person who should be in charge.

But in this particular instance—because there is so much to be fixed in terms of budgetary and personnel issues, and because the individual, Dan Weiss, is very smart, loves art, has a degree in art history, and used to teach medieval art at Johns Hopkins—I think it was the right decision. He is someone who listens, who is analytical, and who I think will do great things with the Met—and someone with whom a director, if they choose well, will do good things.

This arrangement certainly does present certain issues for an incoming director, though. For instance, you mentioned that it will be up to Weiss to stem this tide of departures, and to work with the personnel to preserve the museum’s store of talent. This is an odd climate for a new director to enter, with his staff already having key relationships with a figure on the financial side.

But very quickly a good director will work closely with his curators, and so very quickly Dan Weiss will learn to let go of a whole number of things. And he will say, “OK, while I love to see these things improve, this is your playground.”

If you were in the running to be director today, would you take the job in this situation?

I was in this situation in the early years of my life, only much worse. They plunked somebody from the business world [William B. Macomber, Jr.], who probably never had even visited a museum in his life, to be president. He was entirely about finances, and it was nothing but constant tension. Fortunately, the board realized very quickly that I was the one really running the place, so it didn’t matter very much. [From the New Yorker: “(Montebello’s) way of making it work was to act as though Macomber didn’t exist. De Montebello never consulted Macomber, and never went to his office; if a meeting was scheduled there, he always sent a deputy…. This strategy worked fine. It also made de Montebello something of a hero to the curatorial staff.”]

I don’t think having Dan Weiss in that position is going to dissuade the right candidate. People who are smart are going to realize that this is the Met, so even if they’re not immediately the CEO, they will be able to run the greatest museum in the world, with the acquisitions, the exhibitions, and all the things they love to do if they love art. And, if they do a good job, and Dan has been around for a certain period, their time will come. People shouldn’t expect, at the age of 36, to be number one!

That sounds like good advice.

The situation doesn’t worry me. In fact, it actually expands the range of very good people who can become director, including people who are fundamentally more curatorially minded, who will no longer worry, “Gee, have I got enough management experience? Do I know how to read double-entry bookkeeping?” They’ll come in knowing that someone else is both responsible and accountable to the trustees for that. It opens up a larger field of possible candidates.

Are there any qualities that you believe are de rigueur for an incoming director of the Met at this moment in time?

The Met cannot afford simply to appoint somebody who’s pretty good. They need someone who is outstanding, and someone with enormous breadth. Not a curator who devotes his or her entire life to one decade somewhere in the world. The Met has the art of the entire world, and you need someone with enormous experience, who has traveled a lot, and who has worked in many different kinds of jobs. Someone who will embrace the whole of the institution—who will pay as much attention to a Tibetan Thangka as a Paduan bronze.

Are there people out there who fit this description? Can you say whom?

Of course there are! And no.

Shortly after Campbell announced his departure, the New York Times published an op-ed titled “Why the Met Should Appoint a Female Director,” saying now is the time for the museum to make a groundbreaking appointment and to “lead by example.”

If the Met, after looking at all of the candidates, determines that the one outstanding person happens to be a woman, let them hire a woman director! But to go after a woman director? I’m sorry, that’s ridiculous. The fact is, the Met would have had a woman director after me—they would have had Anne d’Harnoncourt, if she hadn’t died suddenly in June of 2008. There is absolutely no doubt in my mind that she would have been hired. She was relatively young [64 years old], and she was the one person everybody was mentioning to be the director of the Met, but not because she was a woman. Because she was a fabulous person—she was a great director, loved art, all the rest.

Now, Thomas Campbell worked for you, and in fact you helped make his career when you green-lit a $2 million budget for his 2002 exhibition “Tapestry in the Renaissance,” an ambitious show that pulled off the improbable feat of making tapestries chic in art-history circles. When you left the museum in 2008, the board chose him to be director despite the fact that he had little meaningful administration experience, and the fact that his specialty, tapestry, is a very narrow field. Was there any inkling that this historian would turn into such a champion of the contemporary and the digital?

I had no clue. I wasn’t on the search committee—I didn’t want to be. And, as far as I know, there is absolutely no way the trustees could foresee that this man would basically become a totally different human being the day he was made director. I have all sorts of personal theories about what happened, but they’re not worth anything.

Above all, perhaps, Campbell earned an improbable reputation as a technocrat for his efforts to use social media, the website, mobile apps, and partnerships with Google and Apple to grow the museum’s audience. His digital department had a staff of up to 75 people, at a reported cost of $20 million per year—making it bigger than “five or six other departments combined,” according to Vanity Fair.

There were six in that department when I left. I mean, it’s OK to hire 10—but 75? Where was the board?

The board of the Met, of course, is largely composed of businesspeople possessed with tremendous financial acuity.

And they approved everything.

In addition to the museum’s digital makeover, the Met’s most dramatic move in recent years was to take over the Whitney Museum’s former Breuer building, empowering former Tate Modern curator Sheena Wagstaff to turn it into a spinoff museum showcasing Modern and contemporary art in a historical context. What do you think of the Met Breuer, as a concept?

I’d rather not comment.

It would seem like a stark break from your style, considering that your directorship is mainly remembered for your work with the art of the past, from building the new Greek and Roman galleries—and battling the Italian and Greek governments over restitution suits—to making acquisitions like the $45 million Duccio Madonna and Child.

I don’t know, I showed the shark in formaldehyde, I showed Ai Weiwei—I showed just as much contemporary art as this guy did. But I did it in the main building. I didn’t ghettoize it in a secondary building! But I showed a lot of old art too.

I think the concept is to unite them, so that the new art makes the old art sexy while the old art lends the contemporary art some class, like the old quote about Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. Is that a wise pursuit?

I view museums very differently from other people; I concern myself with the very long term. As far as I’m concerned, a museum is a warehouse. It is a library. It is a container. A museum, for me, is a collection of works of art.

So, museums do a lot of silly things. Lots of cafeterias, not enough benches in the galleries, music in the galleries, all the shops, the running around in gym clothes before hours—as Ernst Gombrich used to say, “Museums are killing art with kindness.” But so long as the works of art are intelligently organized, lit, and labeled, in the end it doesn’t matter. The museum is its collections.

I mean, when you’ve got two days in Madrid, are you really going to go online and say, “Gee, I wonder what’s going on right now at the Prado?” You’re just going to go! You go for its collections, and if they happen to have a special exhibition, good. Same as you would go to the Louvre whether or not they have a new Poussin or Lautrec exhibition. So that’s why I don’t worry about all the noise.

At the time of your retirement in 2008, the Atlantic Monthly said that the Met was in the midst of “a golden age”; now, just this year, the New York Times ran a cover story questioning whether the Met was “a great institution in decline.” Do you agree with those assessments? What is needed to begin a new golden age?

Restoring the primacy of art. It has never been lost in reality; it has been lost in the message. So you may have the same wonderful galleries, same exhibitions, et cetera, as always, but if the message that’s going out in every press release and every podcast sends a different signal by emphasizing all of the peripheral things, then, little by little, you spread the sense that the peripheral things are the key. While this may not really be the case, we live in a world where people are influenced by what they see on their phones and listen to on the radio and see on their Instagram. And that message shapes the way people perceive the reality.

So, from that perspective, the digital tools are absolutely critical in terms of restoring the focus of the museum.

The digital tools have to be handled by wise and intelligent people. They cannot be left into the hands of techies, who will focus on the latest craze. Something is trending? Museums shouldn’t be trending! They should set trends.

Speaking of focusing one’s attention, what are the areas of art that you find yourself most drawn to today?

We all have the kinds of art we gravitate to more than others. But you have to understand, I spent more than 40 years of my life as paintings curator then as chief curator and then as director of an institution that has the art of the entire world. Therefore, after working with all the curators, attending every acquisitions meeting, and listening to seminars on works from the entire world, I have become miscellaneous. I have actually learned to like and even love a lot of things that, when I was 25, never would have interested me.

Like what?

It depends from day to day. I’ve learned ways to actually find, in the visual vocabulary of every different genre and medium, the thing that is better, superior. I do believe in hierarchies—which is why I don’t like thematic exhibitions, because they do away with hierarchies. Without hierarchies, you get an exhibition like one the Victoria & Albert did a while ago when they put all of their teacups together. It was awful. Everything was teacups—one was Japanese, one was Chinese, one was 14th-century, one was 18th-century, and it didn’t matter if one was better than another. Museums still have to set standards. There’s no canon—the canon disappeared a long time ago. But standards are different.

Much has been made of your deeply ingrained affinity for the historical, which one could even trace back to your illustrious European family history stretching back to the Napoleonic aristocracy. But I was surprised to learn is that there is also a distinct strain of the avant-garde in your biography. In fact, the reason your parents came to New York in the first place was to raise venture capital for a start-up trying to develop a new form of three-dimensional photography. Did you inherit any of this taste for innovation?

I think what it gives me is the ability to accept that there are many, many forms of art—that a superior artistic sensibility can be at work in any number of media. I’m not a fan of [former Guggenheim director] Tom Krens, but I remember that when he did a show of motorcycles at the Guggenheim people said to me, “Well, were you appalled?” and I said, “No, I was absolutely delighted!” I loved it. Why can’t good design be applied to a machine that moves and makes noise?

At the same time, I would not equate a motorcycle with a painting by Mantegna. They are different categories of things. There are many layers in a painting by Mantegna. There is only one major layer in a motorcycle, or a costume, but that is legitimate layer—which is why we have the Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum, et cetera. There’s room for every major kind of human expression in visual terms.

Earlier, you were talking about the relatively short history of museums, and how they are still early in their evolution. For much of this history, museums focused on the art of the ages, with scant attention paid to the present. More recently, there is a dramatically increased emphasis on the art of the past 100 years, to the extent that one gets the feeling that it’s the marquee attraction. Do you think this is a passing phase, or a more permanent rebalancing of where museums focus their energies?

Too much is made of one supplanting the other—you can do both. But it’s also a question one should ask of economists and sociologists, because it’s so closely tied to the market and the distribution of wealth today.

I think the whole fixation with contemporary art—with which even MoMA has its problems—is going to be with us for a fair amount of time. I don’t see it going away soon.

There is also, over time, the issue of collecting. And because of all the nonsense about UNESCO—how in the 1970s no one could buy anything, forcing us to let loose the greatest masterpieces because somehow they may have been looted from somewhere—there are fewer and fewer collectors of ancient art, and there are fewer and fewer collectors of Old Masters because there are fewer and fewer Old Masters.

You still have Maastricht and so forth, and occasionally a wonderful thing comes up, but there’s no question that the level of works that I used to see at galleries and auctions 40 years ago is completely different from what you see today. The supply, by definition, is limited, and as it shrinks, little by little, this happens. So, I don’t see contemporary art as a vehicle for the collectors of the day disappearing, because what are they going to switch to?

So it comes down to an inventory question in the art market, which animates the boards, the bequests, the fundraising, and everything else.

Even though I think it’s a fiction that everyone loves contemporary art. Some people are fascinated by it, they go and see it. But a lot of people don’t. All you have to do is look at people in museums. I spent my whole life looking at people in galleries. That is how you learn how to hang a gallery—you look where people go. Why is everyone always going to that picture? Is it because it was hung there and not here? I’ve watched a lot of people at the Whitney, at MoMA, and they look with a great sense of curiosity. But most people don’t understand. They would prefer to see the Impressionists, or the Egyptian wing. The contemporary art world is a very small world.

Since we spoke a few weeks ago, your supposed retirement years somehow became even busier with the news that you will now be joining Acquavella Galleries, which is stationed conveniently near the Institute for Fine Arts—and the Met—on 79th Street. What exactly will your role there consist of?

We don’t know yet. The relationship will develop, ideas will come forward from their side and our side, and we’ll see where my advice, my collaboration, will be useful. This could be in terms of exhibitions, of catalogues, of events. I could conduct a panel with some artists and art historians in relation to one of their exhibitions, or contribute to an exhibition catalogue. We have not gotten into any details.

The gallery’s website lists that it works with material going back to the 19th century, with a specialty in such artists as Monet, Renoir, and Van Gogh. Will your remit allow you to go back further in time when it comes to exhibitions?

The gallery is run by the Acquavella family, not by me. I’m an advisor and a director. Those decisions will not be made by me.

I imagine you could be very useful to them when it comes to private sales.

I’m not engaged in sales. I’m not becoming a dealer.

So your input will be primarily from the educational side, through catalogues and panels and possible curation?

And overall advice and things of that sort, through conversation. Anywhere I can be of help I will be, even if it’s just to be present at an opening. I haven’t started, so nothing is very precise and concrete as yet. It’s a relationship that will continue to develop.

You and Bill Acquavella have known each other for decades. How did you first meet?

I knew his father [Nicholas Acquavella]—I used to buy paintings from him. And it all goes back to their gallery. It’s a major gallery—it is the most important gallery of its kind—so it’s a natural fit.