The new book Art= (Phaidon) is a stream of creative consciousness that leaps around the globe and across 6,000 years of art history. To tell this unorthodox story, the book examines 800 works of art and other objects from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Here, we’ve excerpted an array of images and texts that show how a reader might wander from the history of gold in the Americas, to a gold Colombian pendant, to a painting of dancers by Colombian artist Fernando Botero, to a study of Sufi dance, to a book by the Sufi poet Hafiz, and finally to a history of book arts in the Middle Ages.

Gold in the Ancient Americas

In the ancient Americas, gold was a manifestation of the sacred, and objects fashioned from it were a means of connecting with a supernatural world. Far from being passive deposits of wealth, objects made of gold were active agents in an ongoing engagement with powerful forces. Gold was particularly closely associated with the sun; indeed, it was often thought of as an excretion of this divine entity.

Gold was highly valued for its rarity and ability to reflect light, making it a natural choice

for displays of rank and authority. Its immunity to decay has made it a potent symbol for immortality and enduring power worldwide, yet parts of the ancient American world never fell under the sway of gold. For example, the Classic Maya, who flourished in what are now Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, and southern Mexico, displayed little interest in the metal, despite its extensive use by neighbors to the south.

Gold was first exploited in the Andes by the second millennium BC, and from there goldworking gradually spread north, reaching Central America by the first centuries AD and arriving in central Mexico before the end of the first millennium AD. Metalworking was adopted later than other arts in Mexico, but the technology was quickly mastered, and the brilliance and inventiveness of Mixtec and Aztec goldworking traditions remain second to none. For example, a gold labret—an ornament worn through the lower lip—cast in the shape of a serpent ready to strike, is a tour-de-force of Aztec metal-working (p.105, fig.4). The artists who fashioned it not only mastered the essentials of lost-wax casting but took them one step further, by casting the serpent’s retractable tongue as a moving part, creating a gleaming, dynamic ornament that must have terrified the wearer’s enemies on the battlefield.

In the ancient Americas, gold was used primarily to create high-status regalia, including ornaments and vessels, but it was also occasionally used in votive objects, such as small figurines deposited in sacred wells, lakes, or temples, removed from circulation and human view. More often, however, gold was deployed by high-ranking individuals as part of carefully orchestrated performances designed to project magnificence. Dramatic visual effects were paramount, and ancient American artists created ingenious headdresses, collars, and other works, often with multiple components such as dangles or bells, that were designed to reflect light and to dazzle. Such ornaments were, in large part, about establishing identities, asserting status, privilege, and distinction. Sumptuary laws controlled who was able to own what; in both the Inca and Aztec empires, gold was limited to individuals upon whom the emperor had bestowed the privilege, such as members of the royal family and the nobility.

Most ornaments were worn on or near the head, emphasizing its prominence as a locus of perception and communication, and perhaps offering symbolic protection to one of the most vulnerable parts of the body. Artists excelled at creating ornaments for the ears and chest (p.027, fig.4, 6), locations that offer prominence and options for attachment without obstructing sensory functions. In South America, however, artists also created nose ornaments (p.127, fig.5). Suspended from the nasal septum, they would obscure the mouth, masking its movements and perhaps contributing to the projection of the wearer as a supernatural being. In the Andes, elaborate gold vessels became prominent in ritual and statecraft in the latter half of the first millennium AD. Metalsmiths on Peru’s north coast developed a near-industrial level production of beakers made from gold sheet, presumably used in life before they were deposited by the dozen in tombs of high-status individuals. Perhaps the most spectacular objects from this region are large funerary masks, also made of sheet gold. Cinnabar, a red mineral pigment, covered much of the cheeks and forehead of some masks, obscuring the gold surface and suggesting that inherent values of the metal were prized above its surface appearance.

In the sixteenth century, the Spaniards’ seemingly insatiable appetite for gold puzzled Indigenous Americans, and things of incalculable value to them—such as spondylus shells, greenstones, and fine textiles—were initially ignored by Europeans. The

Spaniards’ bottomless desire for gold led to one of the most devastating losses of life in global history, through dangerous forced labor in mines but primarily through the introduction of diseases against which the native population had no resistance. Though some objects were sent back to Europe as curiosities, most works of Precolumbian gold were melted down into ingots for ease of transport and trade. Gold, perhaps the most mutable of metals, would be “reborn” in a new form, remade in the service of new kings and a new god. It would not be until the late nineteenth century that Precolumbian works of art in gold would be valued in their original form, rather than for their material.

Figure Pendant, 10th–16th century, Tairona culture, Colombia

Figure Pendant, 10th–16th century. Tairona culture, Colombia. Gold. Gift of H. L. Bache Foundation, 1969. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Works in gold made by the Tairona people of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in north Colombia emphasize volume and three-dimensional form. This figure is part of a small group called caciques (“cheiftans”) because of their flamboyant, awe-inspiring appearance. Caciques range from one to six inches in height and are hollow, cast by the lost-wax method in tumbaga to achieve remarkable detail. Loops in the back indicate that they were worn as pendants.

Fernando Botero, Dancing in Colombia (1980)

The page of South American art from Art=, featuring Fernando Botero’s Dancing in Colombia (1980).

Botero’s art often depicts people at leisure, shown drinking or dancing. They may seem humorous, but they are often laden with social and political commentary. Dancing in Colombia depicts a lively café scene, overcrowded with seven musicians, two dancers, and a jukebox. Details such as the floor littered with cigarettes and fruit and the exposed light bulbs on the ceiling suggest that the café is rather seedy, attracting clients of a decadent and perhaps immoral nature. One can imagine odors of sweat, tobacco, liquor, and cheap cologne, or the rooms upstairs that can be rented by the hour, although none of this is explicit. Curiously, there is a vast difference in deameanor between the two groups of figures. The musicians stare blankly and seem to be part of an inanimate still life. They are the backdrop for the inexplicably smaller couple who dance with wild abandon, hair and legs flying. Like other works from this period, the surface of this painting is smooth, with few traces of brushwork; color is muted, although small areas of red, yellow, and green appear garishly bright.

Dancing Dervishes, Folio from a Divan of Hafiz, c.1480

Dancing Dervishes, Folio from a Divan of Hafiz, c.1480. Painting attributed to Bihzad. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Rogers Fund, 1917. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This painting shows dervishes in the mystical ceremony of the sama, in which whirling and dancing are accompanied by music and recitations of a dhikr, a repetition of the name of God. In their mystical dance, Sufis achieve an ecstatic state, facilitating their connection to God. In the foreground, dervishes are shown in various stages of entrancement and exhaustion, their scattered turbans thrown aside in the bliss of divine ecstasy.

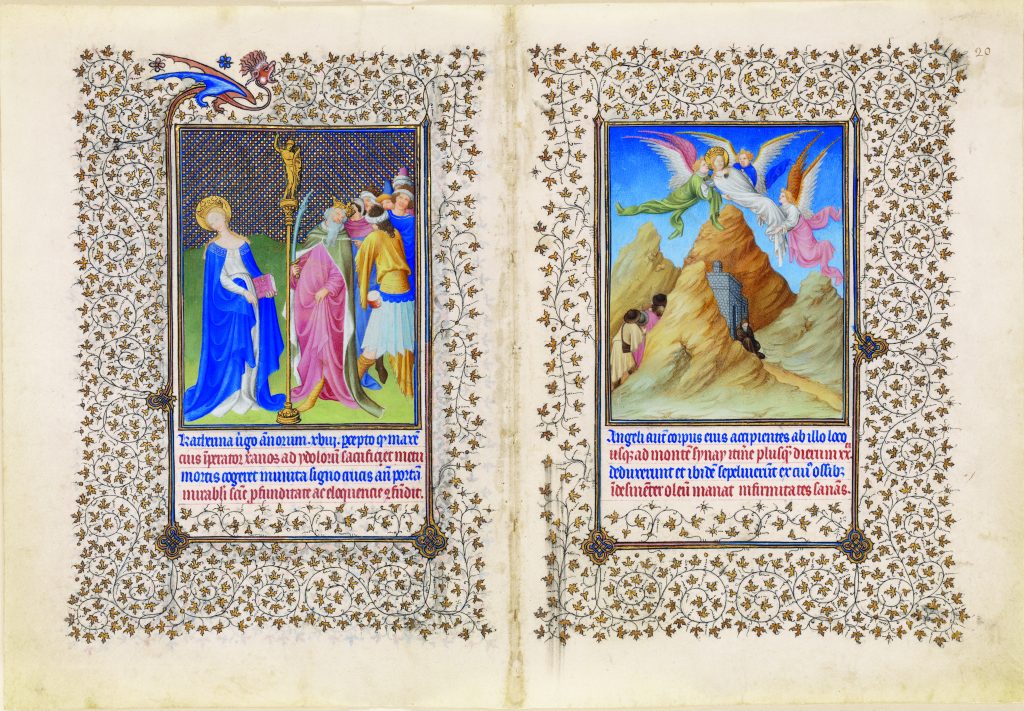

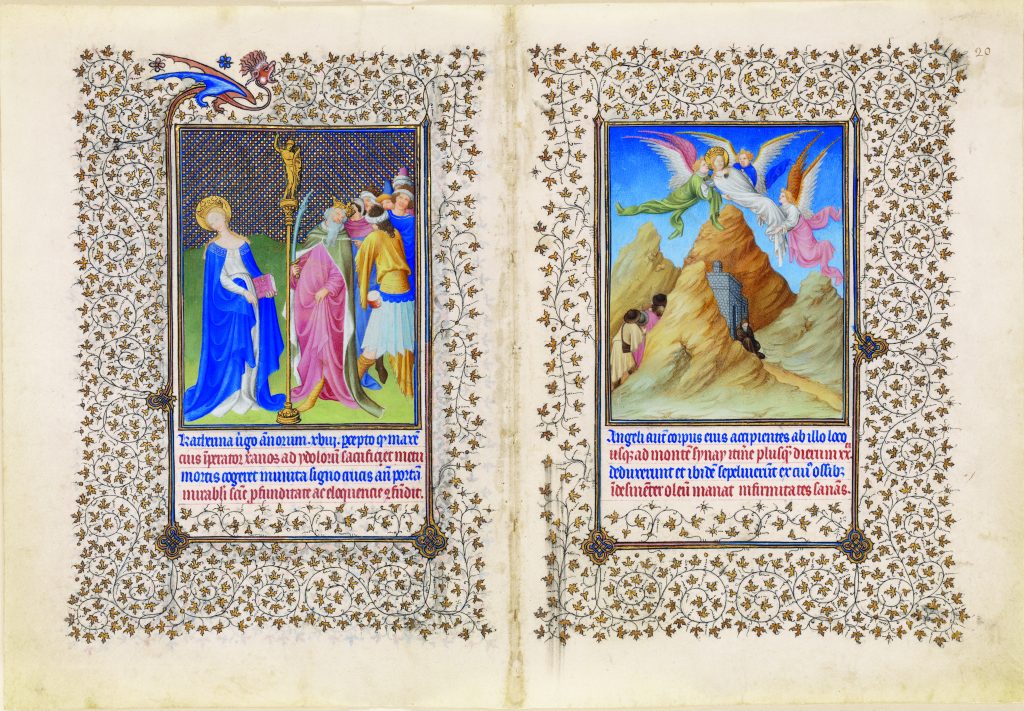

The Limbourg Brothers, the Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, 1405–08/09

The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, 1405–08/09. The Limbourg Brothers. Tempera, gold, ink on vellum.

The Cloisters Collection, 1954. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Probably created in Paris, the Belles Heures, or Beautiful Hours, a private devotional book, is one of the most sumptuous manuscripts to have survived from the Middle Ages. Commissioned by Jean de France from the Limbourg brothers, the most gifted artists of their time, it is the only manuscript completed by them in its entirety. The richly illustrated text is enhanced by seven unprecedented picture cycles devoted to Christian figures or events that held special significance for the duke. Using a luminous palette, the artists blended an intimate Northern vision of nature with Italianate modes of figural articulation. The keen interest in the natural world and the naturalistic means of representing it, so striking in the 172 illuminations, foreshadow the work of Jan van Eyck and the ensuing generations of outstanding 15th-century South Netherlandish painters.

Excerpted from Art =. Discovering Infinite Connections in Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Phaidon.