Art & Exhibitions

10 Critically Acclaimed Art Exhibitions We Wish We Saw in 2020 But Weren’t Able to Because… You Know

This interminable year is finally coming to a close. But we cannot help but reflect on the great cultural moments we missed.

This interminable year is finally coming to a close. But we cannot help but reflect on the great cultural moments we missed.

Artnet News

Need we say more? And so, without further ado…

Steve McQueen, Film Still of Charlotte (2004) © Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery.

It’s been thrilling to watch Steve McQueen break out of the art world to create stunning films like the Academy Award-winning 12 Years a Slave and the new quintet (quintet!) of feature films, Small Axe, that he’s created for Amazon Prime, which I’m working my way through now.

But he got his start as, and remains, a visual artist. I’ve gotten to see a few of these works, like the brutal 7th Nov. (2001), in which the artist’s cousin, Marcus, tells the grim story of accidentally shooting and killing his own brother; End Credits (2012–ongoing), which scrolls through thousands of pages of redacted documents from the FBI file of African American actor and Civil Rights activist Paul Robeson; and Charlotte (2004), in which the artist’s finger, in extreme close-up, pokes at the eye of actress Charlotte Rampling in an exploration of sight and looking.

It stings, though, to miss a show Time Out and the Guardian both gave five stars. I’m stuck in New York, in this same damn studio apartment I’ve been in alone for nine months, so I didn’t get to see this retrospective of three decades.

Oh well, back to Small Axe!

—Brian Boucher

Frank Walter, installation view at Museum MMK, Frankfurt am Main. Photo: Axel Schneider.

I sadly missed a major retrospective on Frank Walter at MMK in Frankfurt am Main—an fascinating subject in any year, but a show that felt even more urgent during this summer of resurgent Black Lives Matter protests.

The Antiguan and Barbudan artist is difficult to categorize—”there is no typical Frank Walter,” wrote the museum’s director, Susanne Pfeffer, in an accompanying show text. His varied work ranges from abstract pieces on cardboard to figurative paintings to sound recordings.

His incredible life and oeuvre is charted through the show. Born a descendant of slaves and plantation owners, Walter went on to become Antigua’s first plantation manager of color in the sugar industry. He traveled to Europe to learn about agriculture in hopes of improving working conditions back home, while also seeking out his German ancestry, though he encountered racism almost everywhere he went. He returned to the Caribbean and exiled himself to a self-built studio until his death in 2009.

Despite the enormity of his practice (he made over 5,000 paintings and wrote 50,000 pages of prose), Walter never had a major exhibition in his lifetime. His work at MMK was shown in dialogue with artists whose works touched on colonial and post-colonial subjects: There are Marcel Broodthaers’s enigmatic palm trees installed at the entrance; Kader Attia’s broken and restitched mirror; and Howardina Pindell’s accounts of racist violence throughout her youth in the 1980 film work Free, White and 21.

–Kate Brown

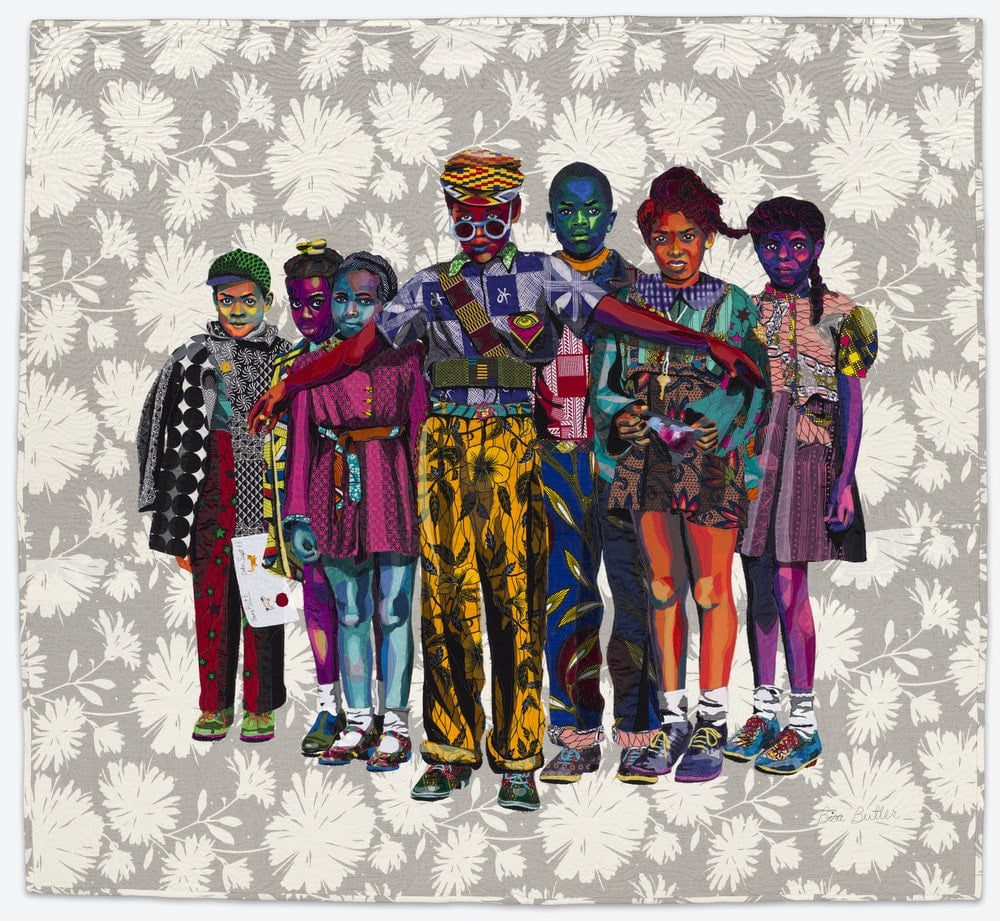

Bisa Butler, The Safety Patrol (2018). Photo courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago, Cavigga Family Trust Fund.

I first discovered Bisa Butler in 2018 at the Pulse art fair in Miami. I was invited to stop by the day before the show’s opening for a one-on-one tour with then-director Katelijne De Backer. When I asked her about the fair’s highlights, she led me straight to the booth of New York’s Claire Oliver Gallery, which had pre-sold four of Butler’s figurative quilted works to museums such as the Art Institute of Chicago.

The works were stunning. Figurative compositions in boldly unconventional color combinations, made entirely of quilted fabrics, they were a powerful argument for the worth of a traditionally marginalized medium. Butler uses thousands of tiny pieces of vibrantly patterned African fabrics to create striking portraits based on historical photographs of Black men, women, and children, celebrating both African American quilting traditions and Black identity.

It was the best thing I saw at any of Art Basel’s satellite fairs that year. Two years later, I was so excited to learn that a whole show of her work was coming to the Katonah Museum of Art that I highlighted it as an exhibition to watch in a story we published on March 9—the second-to-last day I went into the office, shortly before our worlds were turned upside down.

The show’s opening was delayed until July, but by the time I felt safe enough to venture out, there were no tickets available in a time slot that worked for me. After closing in early October, it traveled to the Art Institute of Chicago, where it is on view until April 19. So there’s still a glimmer of hope for me—but I’m not holding my breath.

—Sarah Cascone

Agnes Pelton, The Ray Serene (1925). Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The strain of late-19th to early-20th-century spiritualist art that has recently captivated museum-goers hardly seemed imaginable before the Guggenheim’s surprise hit exhibition, “Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future,” which last year became the museum’s most-visited show ever.

But then, on the heels of that exhibition, came the Phoenix Art Museum’s critically acclaimed retrospective of the paintings of Agnes Pelton, another “rediscovered,” tacitly feminist pioneer of Modernist abstraction who worked with occult traditions.

That show traveled to the Whitney Museum in New York, opening on the inopportune date of March 13, 2020, the day the White House declared a national emergency.

Pelton, who was born in 1881 (just two decades after Klint), pursued her interests in theosophy, astrology, and yoga before retiring to the desert landscape in California, where she completed the paintings that made up the heart of the Whitney show. I have never gotten to see Pelton’s work in person, but many of her most salient themes—solitude, a return to nature, and the collision of cosmic forces—seem like they would have felt especially pertinent this year.

—Rachel Corbett

Jacob Lawrence, Massacre in Boston (1954). Photo courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Compared to the earlier “Migration” series (1940–41), Jacob Lawrence’s “Struggle: From the History of the American People” series (1954–56) is much, much less well known. Strangely, this might be because its overall subject matter is more well-trodden territory, embracing the overall history of the United States rather than honing in on the specific drama of Black life. “I think the general public didn’t know what to do with it,” curator Lydia Gordon has said. “He’d gone beyond the boundary of how he was defined and understood, as a Black artist depicting Black history.”

“Struggle” has a patriotic though unsettled tone, in some ways making it even more an essay in the contradictions of what W.E.B. DuBois called “double consciousness“, the sense of being torn between Black and American identities. So, on the one hand, Lawrence’s multifaceted, expressionistic retelling of the story of the United States put his stamp on familiar civics beats like the Founders at the Constitutional Convention, Hamilton’s duel, or Madison going to war with the British in 1812. But it also lingers pointedly on images like a fallen Crispus Attucks, the Black Native American worker who was the first to die in the Boston Massacre. One panel even enigmatically dramatizes a slave uprising that never happened.

In this Hamilton: The Musical era, when liberal hunger to re-narrate the past through a more inclusive lens sit in sometimes uneasy tension with demands to look unsparingly at just how brutal and oppressive that past really was, I think there’s something illustrative about how unresolved Lawrence’s overview is, zigging and zagging through US history in this Cold War-era series, cutting a path as restless as his own lines. And aside from being interesting as a document, this series is also, of course, a chance to see Lawrence at work as a great painter—all the more reason I wish I’d had the chance to see it in person.

—Ben Davis

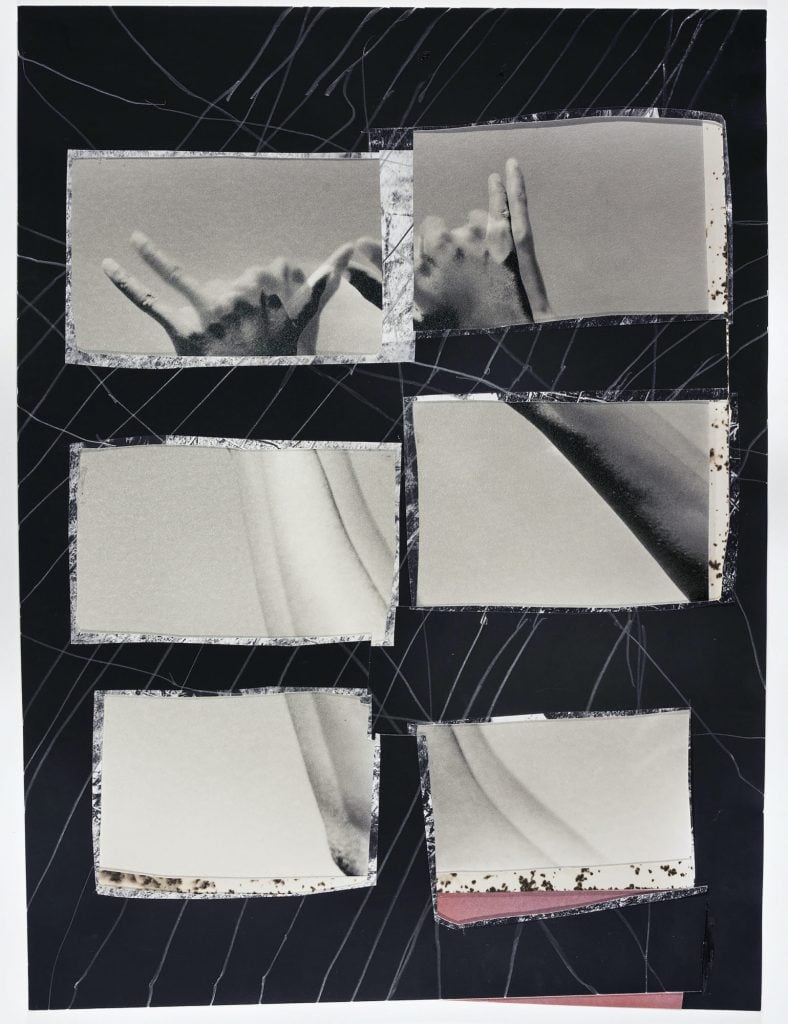

Dionne Lee, True North (2019). Courtesy of the artist. © Dionne Lee.

Agree with it or not, MoMA’s long-running “New Photography” series has earned a reputation as a bellwether for emergent trends in the medium, christening many an “artist to watch” in its 35 years. This year’s iteration, pushed online by the pandemic, arrived rather quietly in late September on MoMA’s online Magazine platform. You can still view it there, but it’s hard not to imagine the virtual show as a shell of what it would have been in any other year.

It’s not just the detachment that comes with viewing art online, or the screen fatigue; it’s that “Companion Pieces,” as the show is called, concerns itself with the physicality of photographs and their context. Many of the artworks—from quant still lifes in wallet-sized frames to canvas colleges that run the length of a wall—demand to be viewed in person.

“Rather than thinking of them as discrete images or art objects,” the exhibition’s curator, Lucy Gallun, told me last month, “I was thinking about how images don’t live in isolation and how artists have recognized that. I felt like I was seeing many artists take up this idea of one image being dependent on another, or looking back to an older picture to say something new about today.”

Gallun’s show is unlike any other in the “New Photography” canon, and it’s a shame it didn’t get the rollout it deserves. Still, much of the work transcends the limits of its presentation—particularly a pair of contemplative, dialogic series by Indian artist Sohrab Hura and the politically-inclined photomontages of Dionne Lee. It’s all well worth the (free) price of admission.

—Taylor Dafoe

Installation view, “Artemisia” at the National Gallery.

There are shows that people say are once-in-a-lifetime that actually get revisited, in one form or another, 10 years later—and then there are shows that really, truly probably won’t come around again. I hope the National Gallery’s show of work by Artemisia Gentileschi is the former. The institution’s first-ever exhibition dedicated to a historical female artist brings together 29 luminous works by the Old Master, who rose to fame in the 17th century by painting women in ecstasy, exacting revenge, and making art.

Until recently, Gentileschi was known largely for her dramatic life story; specifically, the trial of her art teacher for her rape (the court records are included in the show). But this show—at least as far as I can tell from the photos and catalogue—complicates that narrative. We can revel in her craft, her ability to render emotion, action, and light—and even grasp her true savvy. Embracing her notoriety from the trial, she seemed to brand herself as a painter of vengeful women.

A show with that kind of complex, ambitious, talented protagonist is one I hope will be renewed in another season.

–Julia Halperin

Installation view of ‘Gerhard Richter, Painting After All’ at The Met Breuer, 2020. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by Chris Heins

It was only about week or so into the citywide New York shutdown that I spoke with Sheena Wagstaff, the head of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Modern art department and the organizer of “Gerhard Richter: Painting After All.” The 60-year survey of more than 100 works was his first major New York show in nearly 20 years, and one of the most highly anticipated of the spring 2020 season. It had just opened at the Met’s Breuer outpost, and now it was already shut, along with the rest of the city.

“At least it’s up until July,” Wagstaff told me, which seemed a reason to be optimistic at the time. But in the background hung a lingering problem: because of the planned handover of the Breuer building to the Frick Collection, the Met had no option to extend the exhibition.

A focal point of the Breuer show was the artist’s “Birkenau” series, painted in 2014, for which he took, as his source, smuggled photos by prisoners from inside the notorious Nazi concentration camp in Poland. The artist’s continued experimentation and reworking of the canvases eventually rendered the imagery unrecognizable, but the work is no less dark for it.

To the extent that there is a silver lining here, as a kind of “coda,” the Birkenau paintings got their own miniature spotlight at the Met’s main building upon its reopening this summer. “I feel that we have recovered some trace of the exhibition and [it’s] relevant to this new audience that we have now, which is a totally local audience,” Wagstaff told Artnet News. “We don’t have tourists anymore.”

—Eileen Kinsella

Donald Judd, Untitled (1991) Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2019 Judd Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: John Wronn.

In the Park Slope Barnes & Noble, where I spent a lot of time as a teenager, the art book section was quite small. I think most of the books were about Monet, and I hated Monet and his stupid frivolity. But I did like Donald Judd, who I learned about one day after coming upon the art historian James Meyer’s book on Minimalism. His artworks were simple, clean, elegant, and bold. And they were built from ideas that were completely incomprehensible to me.

I’ve written about Judd a lot since then (on his writings, his place in the Minimalist canon, etc., etc.), so I was enormously excited, several years ago, when MoMA announced a retrospective on the artist. The show was long delayed: first scheduled to take place in 2017, it took another three years to come together. And then—what good fortune!—it finally opened just days before New York went into a full shutdown.

I could go see it now. The museum, as of this writing, is open to the public with safety measures in place. But my priorities have changed, and nothing seems more frivolous now than going to a museum in a pandemic.

–Pac Pobric

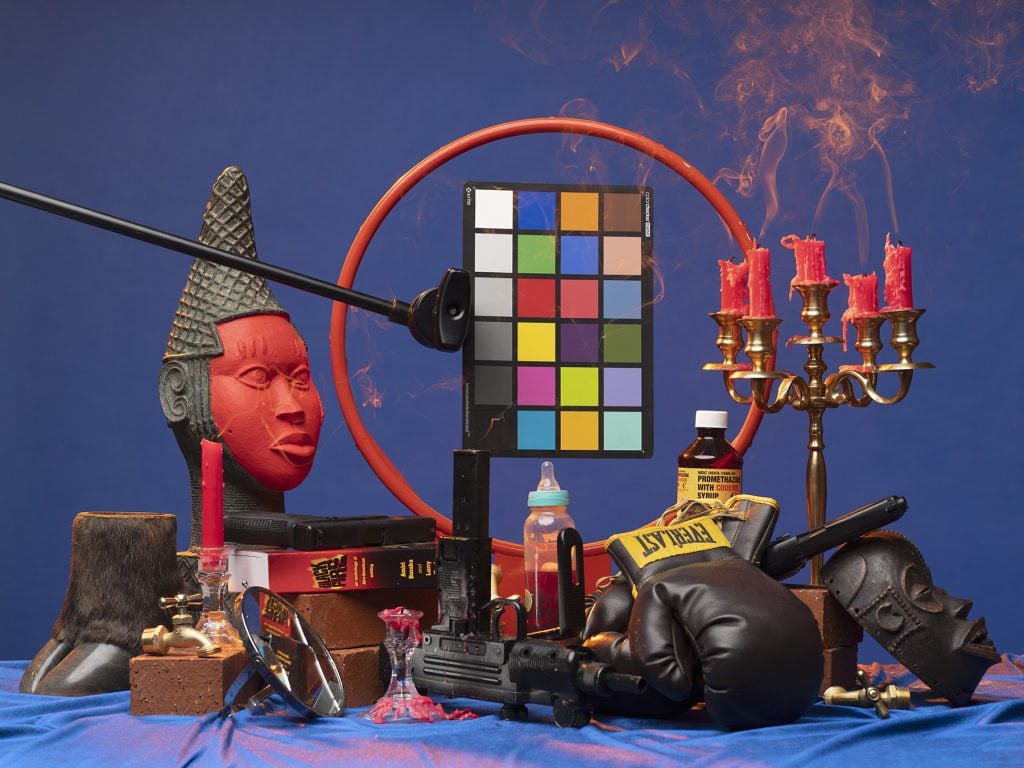

Awol Erizku, Black Fire (Mouzone Brothas) (2020). Courtesy the artist and Ben Brown Fine Art.

In a year defined by the twin forces of the pandemic and the struggle for racial justice, I thought a lot about how a society can’t evolve its policies without first evolving the language and imagery it uses to discuss the underlying issues.

Awol Erizku’s “Mystic Parallax” dovetailed with this line of thinking by using a multiple-media tour de force to channel viewpoints on African and African diasporic culture that disrupt the Eurocentric terms that have dominated the discourse in the West for too long—and caused far too much tangible harm in the process.

Leveraging formats ranging from short films and photo-based works, to sculptures and a soundtrack by Christian Scott, Erizku aimed to advance arguably the most important conversation of my generation in arresting fashion. Energized by influences as diverse as Islam and Trap music, the exhibition animated the fundamental truth of Africa as a vibrant collection of 54 distinct countries, each formed by its own dynamic history and intra-national diversity of peoples now spread around the globe. While it undoubtedly would have made an even stronger impression on me in the flesh, the virtual tour of the show still acts as a sensory treasure and a visceral motivator to bridge the sociocultural divides separating our broken present from a just future.

—Tim Schneider