Analysis

After a Dip, the Market for Gerhard Richter’s Work Is Back on Solid Footing. Here’s Which Bodies of Work Are Thriving

Market insiders say Richter's market is actually composed of a number of submarkets.

Market insiders say Richter's market is actually composed of a number of submarkets.

Eileen Kinsella

German artist Gerhard Richter is widely regarded as one of the most important—if not the most important—artists of the 20th and 21st centuries.

His distinctive, large-format abstract paintings and Photorealist-style works, many of which embrace dark, complicated moments in history, have made him among the most sought-after—and expensive—living artists of our time.

“Richter is one of the great painters of the 20th, and now 21st, centuries, and there are more than two great threads in his practice,” says Katharine Arnold, a Christie’s postwar and contemporary art specialist. “He’s almost a bit of a polymath. All of those different parts make him an extraordinary and versatile artist.”

But the past few years have not been without their challenges in the Richter market.

In recent years, intense (some might say frothy) demand pushed prices for his abstract paintings to aggressive levels that peaked around 2015, on the heels of a major Tate Modern retrospective.

Depending on which expert you speak to, prices for either cooled down a bit in the aftermath of the show, or demand eventually satisfied supply, after the market peaked with the sale of a $46 million work at Sotheby’s London in February 2015.

Gerhard Richter, Abstraktes Bild (801-3) (1994). Image courtesy Phillips.

Despite the fact that the trade in large Richter abstracts has slowed down a bit, the overall market is still going strong, albeit at a lower level, numerous auction experts and advisors said.

At Phillips’s recent major summer auction, a picture titled Abstraktes Bild (801-3) (1994) hammered at just over $3 million, a hair above its high estimate. (With fees, it went for $3.7 million.)

Since the sale, there have been two more private Richter sales for similar works and at similar prices, says Jean-Paul Engelen, Phillips’s deputy chairman.

But in the past, when demand has risen and driven up estimates, activity has intensified. “Then you hit the point where it breaks, and you have to restart about 20 percent lower. Now it feels very solid again,” Engelen says.

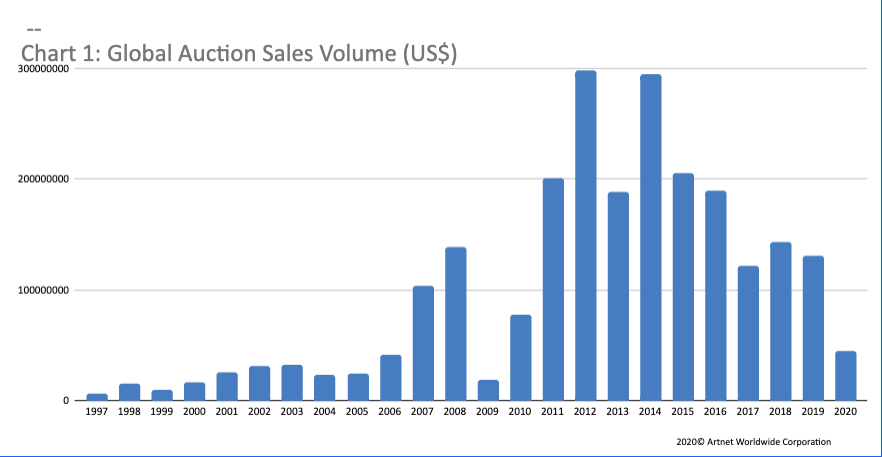

Courtesy of Artnet Analytics.

According to the Artnet Price Database, 25 Richter works have sold for more than $20 million each, and 19 of those were abstract paintings.

David Galperin, a Sotheby’s senior vice president, said the “significant boom in prices for late 1980s abstract works” between 2012 and 2015 was well deserved, given the surge of interest among contemporary collectors. Several experts noted strong demand from Asian collectors in particular during the peak period.

Yet “there isn’t one overall market, but a number of different ones,” for Richter’s work, Galperin says. “He constantly reinvented himself, so there are many discrete bodies of work. Prices at auction reflect that and you see different shifts occurring in submarkets.”

At a certain point, after buyers found the abstract works they were looking for, they shifted to other areas of Richter’s oeuvre, Galperin says, noting that collectors tend to buy the artist in-depth.

He adds that the market for smaller and medium-sized abstract works in the $10 million and under range is particularly robust right now, especially for works from the early 1980s, before the artist abandoned paint brushes altogether and embraced squeegees. Galperin said the area was “undervalued but [was] starting to grow.”

Installation view of “Gerhard Richter: Painting After All” at the Met Breuer, 2020. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by Chris Heins

Even some market experts appear to have been taken aback by the spike in prices for the abstract works, noting the longtime focus of connoisseurs on Richter’s figurative paintings and landscapes.

“The momentum had always been for the figurative paintings,” art advisor Wendy Cromwell says. “We didn’t see a run-up in the way there was with the pricing for abstract paintings.”

The highest price ever paid for a non-abstract was $37 million, for Domplatz, Mailand (Cathedral Square, Milan) (1968), a top tier work by any measure. Experts say nothing of this caliber has come to the market since it sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 2013.

A huge plus for Richter’s market has been careful management, including by his longtime dealer, Marian Goodman. The artist has also kept solid documentation of his work, which is especially useful for aspiring buyers.

“From a market perspective, the fact that there is so much clarity gives [collectors] confidence,” Engelen. “The more clarity, the stronger the market.”

Installation view of ‘Gerhard Richter, Painting After All’ at The Met Breuer, 2020. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by Chris Heins.

For the everyday Richter fan, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Gerhard Richter: Painting After All,” a 60-year survey of more than 100 works, was his first major New York show in nearly 20 years, and one of the most highly anticipated of the spring 2020 season.

But the exhibition prematurely shuttered after only nine days due to widespread shutdowns across the US. (In part because of the planned handover of the Breuer building, where the show was staged, to the Frick Collection, the Met had no option to extend the exhibition upon its reopening.)

A focal point of the Breuer show was the artist’s “Birkenau” series, painted in 2014, for which he took, as his source, smuggled photos by prisoners from inside the notorious Nazi concentration camp in Poland.

The artist’s continued experimentation and reworking of the canvases eventually rendered the imagery unrecognizable, but the work is no less dark for it. Also hung prominently at the entrance was another “history” painting: Richter’s September (2005), a distorted but clearly identifiable image of the Twin Towers in Lower Manhattan, moments before the second airplane hit on 9/11.

“I think Richter regarded this show as one of the most important exhibitions he has ever done in his life,” says Sheena Wagstaff, who organized the show with Benjamin Buchloh. This show was “about demonstrating how far he has been able to use painting, to push it to its extreme in its ability to wrestle with the kind of imagery that the Birkenau paintings are based on.”

As a kind of “coda,” the Birkenau paintings will get their own miniature spotlight at the Met’s just re-opened main building on Fifth Avenue.

“I feel that we have recovered some trace of the exhibition and that this is relevant to this new audience that we have now, which is a totally local audience,” Wagstaff says. “We don’t have tourists anymore.”