Art World

Need Some Hugspiration? Here Are 4 of Art History’s Most Romantic Embraces, From a Pair of Stone-Cold Lovers to a Gilded ‘Kiss’

Sometimes we all just need a hug.

Sometimes we all just need a hug.

Caroline Goldstein

So many people around the world have been deprived of human touch this past year, and the physical connection that comes with a good hug. As Valentine’s Day approaches, that longing may come into even starker relief. So whether you’re alone for the holiday or celebrating with a loved one, we’ve rounded up three of the most enduring depictions of embraces in art history to honor the spirit of physical affection—which we all hope to share again soon.

Antonio Canova, em>Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1787–93). Collection of Louvre Museum, Paris.

The story of Cupid and Psyche is a classic tale of lovers overcoming endless obstacles, including betrayal, separation, disapproving parents, a near-death experience, and the fact that she was a mere mortal and he the god of love. Of course, in the end, love does indeed conquer all.

In the second century, Lucius Apuleius’s novel Metamorphoses detailed the tumultuous relationship, which became a popular theme in artworks across mediums. The tale begins with Psyche, a beautiful girl born to nobility and treated with the deference of a goddess, who was punished by the vengeful Venus for attracting such devotion as a mortal. She sends the god of love himself, Cupid, to curse the young woman, but upon laying eyes on Psyche, Cupid falls hopelessly in love with her. He visits her nightly and implores her not to look at his face, lest she realize who her lover is. Unable to resist, Psyche betrays her beloved’s confidence and peeks through the shadows to see him.

Yet again, Psyche is punished, this time forced into a deathlike slumber. Cupid, though, cannot bear to live without his beloved and awakes the sleeping woman, kneels beside her, and wraps his arms around her. That is the moment Italian sculptor Antonio Canova immortalized in his famous marble, Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss.

When Flaubert saw the work, he, too, couldn’t resist physically kissing the statue himself. The French novelist recalled first placing his lips on “the armpit of the swooning woman stretching out her long marble arms to Cupid. And then the foot! The head! Her face! Forgive me, but it was my first sensual kiss for so long; indeed it was something more; I was kissing beauty itself.”

Renoir is best known for his portraits of everyday life, rendered in the thin, loose brushstrokes common in the Impressionism of the 19th century. But by the time he composed Dance in the Country and its companion piece, Dance in the City, the artist was at a crucial turning point in his career.

“In 1883 there was a kind of break in my work,” Renoir said years later. “I had come to the end of Impressionism and I arrived at the conclusion that I knew neither how to paint nor draw. In a word, I was at an impasse.”

That desultory analysis belies the success of the jovial Dance pieces, which were commissioned by the legendary art dealer and patron Paul Durand-Ruel and now hang in the permanent collection of Paris’s Musée d’Orsay.

The artist had recently returned from a trip to Italy, where he had stayed with his friend, the painter Paul Cézanne, and immersed himself in the work of Raphael. He had come to the conclusion that he would stray from the main tenets of Impressionism and follow Cézanne’s groundbreaking path. In Dance in the Country, the figures are more clearly defined, and though the scene is bathed in warm light, it emanates from the woman’s dress and straw hat rather than a traditional light source.

Renoir’s good friend Paul Lhôte served as the model for the gentleman, dressed smartly in a dark suit with his arm securely wrapped around his partner. The woman is believed to be Aline Charigot, who later married the artist and continued to serve as his model and caretaker as his health deteriorated. The woman’s gaze meets directly with the viewer’s and she smiles with flushed pink cheeks, perhaps sharing an intimate moment with the man as an audience forms around them.

The embrace is one of companionship and commitment, perhaps her direct gaze a sign of fortifying support for Renoir as he ventured out In new directions in work and love.

Perhaps the first image that comes to mind upon hearing “embraces in art history” is Gustav Klimt’s most famous work, The Kiss (Lovers), completed during his so called “Golden Period” in the early 20th century.

Painted in the lavish style of Art Nouveau, and the epitomizing work of Vienna Secessionists, the canvas gleams with applied gold leaf, giving it an aura of majesty and preciousness. The couple, who may be modeled after the artist and his lover Emilie Flöge, are so tightly entwined, with a halo illuminating their joined frames, that they appear to be one singular being. This expression of devotion is enhanced by the mysterious environment they inhabit: a golden background wherein the couple is perched on the edge of a flowery patch, as if they are the only two people in existence.

The man, dressed in flowing robes adorned with spirals and dark geometric patterns has his head, crowned with leaves, bent over the woman to kiss her cheek, his hands cupped around her head. She, in turn, wears similar robes with a floral motif that recalls the natural shapes popularized in the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movements. The woman appears besotted by her companion, closing her eyes and sinking into his frame, one arm wrapped around his neck.

The work is actually a synthesis of the many stylistic advances within art, including Japanese prints and Byzantine mosaics, culminating in a timeless, sensual image.

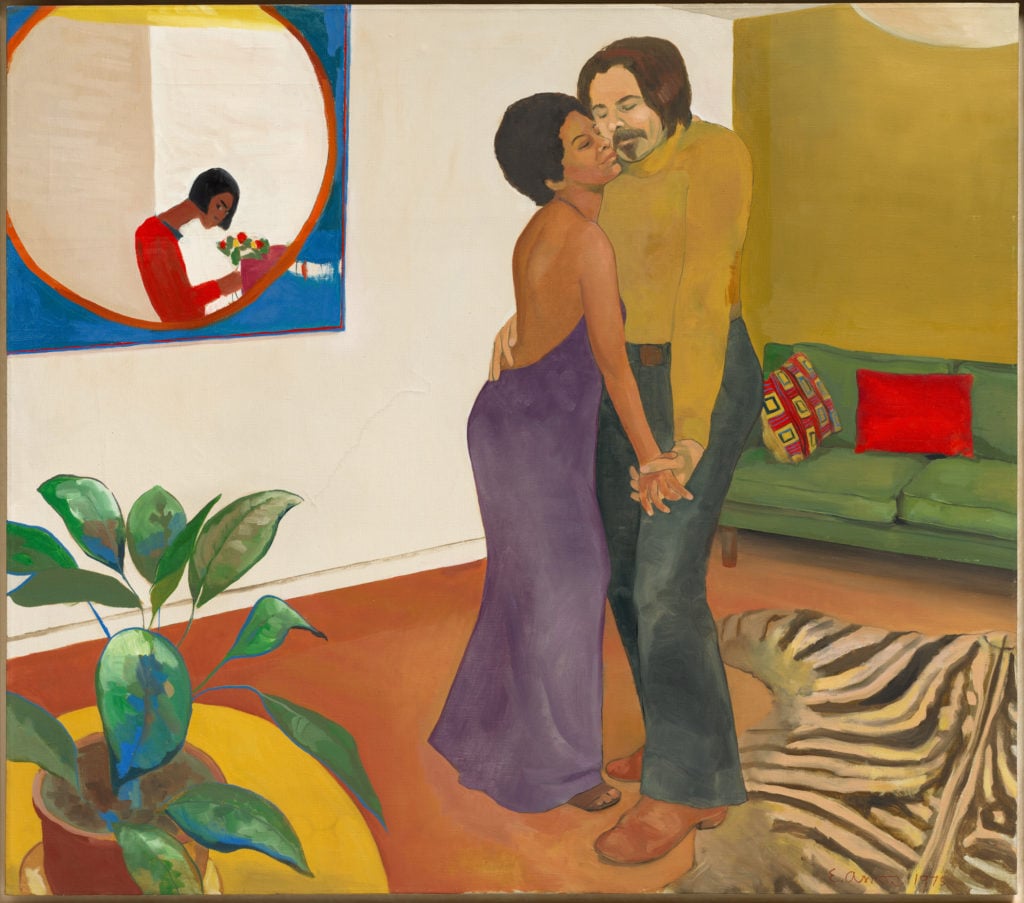

Emma Amos, Sandy and Her Husband (1973). Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Gorgeous and stylish, Sandy and Her Husband is a painting of aching everyday intimacy. The couple sways together in their stylishly appointed apartment, fingers woven together, eyes closed, lost in a song we can’t hear and sharing a moment. Their apartment is decked out in full ’70s style, in the artist’s lush palette.

For our money, it’s one of the most romantic of all contemporary paintings.

Amos, who was associated with the famed Spiral group of Black artists and spent decades chronicling Black life in her sharply observed art, is having a moment right now. And partly that moment is owed to the magic of this painting, which was a centerpiece of “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85,” a hit show at the Brooklyn Museum from a few years ago. It was quickly acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art.

“I hope that the subjects of my paintings dislodge, question, and tweak prejudices, rules, and notions relating to art and who makes it, poses for it, shows it, and buys it,” Amos wrote in her artist statement.

You can tell that the quiet rapture of the painting is special to Amos, because she’s painted herself into their apartment: the image of the wall to the left behind them is her own self-portrait, Flower Sniffer (1966).