Art History

4 Art-Historical Masterpieces That Would Not Have Existed Without the Great Love Stories That Inspired Them

Learn more about the sculpture that broke ties between Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel, among other artistic upheavals.

Learn more about the sculpture that broke ties between Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel, among other artistic upheavals.

Katie White

Love affairs are an art form all their own when two creative spirits become romantically entangled. Though the myth of the artist as a solitary genius endures, many of history’s greatest painters and sculptors found artistic inspiration in a muse, rival, collaborator—or someone who happened to be all three. Though these artists’ epic love sagas often flamed out in spats of professional jealousy, infidelity, and addiction, they also—while they lasted—sometimes gave birth to great works of art.

To mark Valentine’s Day, we decided to share the stories of four love affairs—and how they shaped masterpieces of art history.

Raphael, La Fornarina (1518–1520). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Unconfirmed Bachelor: When Raphael died in 1520, he was, officially speaking, a bachelor who was engaged to the niece of a powerful Vatican cardinal. But rumors over the centuries endured that he had a mistress, one Margherita Luti, a baker’s daughter from Siena. If true, the disparity between their respective positions would have been almost unimaginable—Raphael was a true celebrity of the Renaissance, known everywhere he went, and she, an unknown laborer.

An Artistic Nuptial Clue: Many art historians believe Raphael’s painting La Fornarina (which can be translated The Baker’s Daughter) provides clues into his relationship with Luti and even suggests that the two wed in a secret ceremony. In the painting, a woman looks out from the canvas with a hypnotizing gaze, a diaphanous veil falling across her bare stomach, placing her hand atop her breast. It is a romantic riddle filled with possible allusions to nuptials. First, there’s a brooch pinned to the woman’s silk turban, an adornment commonly worn by a bride. Meanwhile, the brooch’s pearl can be read as an allusion to the sitter’s name: Margherita is the Latin word for pearl. What’s more, a ring originally appeared on the sitter’s left hand, but was subsequently covered up after Raphael’s death. Other hints include the presence of myrtle and quince, which are symbols of love, fecundity, and fidelity.

A Cover-Up?: Many believe that after Raphael’s death, his students attempted to obscure Luti’s existence. They painted over both the myrtle bushes and the ring, which were only later uncovered during cleaning. Why? At the time of his death, the school was in the midst of a Vatican commission. If his betrothed, Maria Bibbiena, and her cardinal uncle learned about Luti, the loss of the commission would have bankrupted the studio. In an attempt to silence the rumors, Raphael’s students even had a plaque placed on his tomb in memory of his fiancée. Meanwhile, four months after his death, the convent of Sant’Apollonia in Rome’s Trastevere quarter registered the arrival of “widow Margherita,” the daughter of a Siena baker.

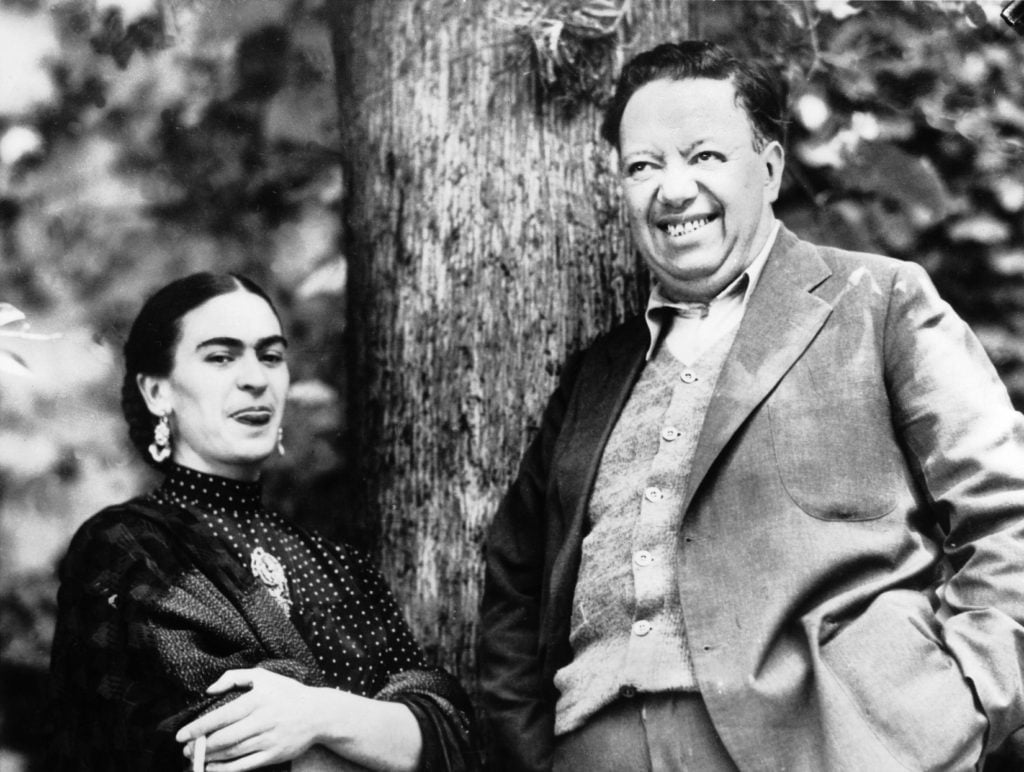

Frida Kahlo, Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931). Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.

A Rocky Romance: The titans of Mexican art wed in 1929, when Kahlo was just 22 and Rivera, 43. Throughout their tumultuous union, each tirelessly championed the other’s artistic vision (Kahlo’s disapproving parents coldly nicknamed the pair “The Elephant and the Dove”). They split in 1939 only to remarry the very next year. “I suffered two grave accidents in my life,” Kahlo once remarked. “One was the trolley, and the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst.”

Portrait of a Marriage: In 1931, two years after they wed (the first time), Kahlo painted what at first glance appears to be a traditional wedding portrait. Entitled Frieda and Diego Rivera and now in the collection of San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, the image was created during their stay in San Francisco, where Rivera had been hired to paint a mural for the city’s stock market. Albert Bender, one of Rivera’s first American patrons, commissioned the painting from Kahlo. But even just two years in, their marriage was in turmoil. Rivera was involved in an intense affair with the American tennis star Helen Wills.

Devils in the Details: Kahlo hints at their estrangement in the painting. Rivera’s body turns away from hers; their hands only slightly touch. She also alludes to the differences in their stature through dress: she is pictured in traditional Mexican attire, while Rivera wears an American-style suit—a mark of his ease, comfort, and success amid worldwide acclaim.

Camille Claudel, The Mature Age. Collection of the Musee D’Orsay.

A May-December Romance: From the very beginning, the romance between Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel was on unequal footing. In 1884, when they met, Claudel was a 19-year-old student, hired as an assistant in Rodin’s studio. He was in his mid-40s with a career on the rise and in a more than 20-year relationship with another woman.

A Talent All Her Own: In the studio, Claudel was tasked with many of the most difficult jobs, such as working on the hands and feet of sculptural figures. She had an influential role in completing two of Rodin’s most famous works, The Burghers of Calais and The Gates of Hell. (Unsurprisingly, she received no credit.) Rodin, for his part, was enamored of both Claudel’s talent and her beauty, making several portraits of her. She sought, mostly unsuccessfully in her lifetime, to be recognized as an independent artist at the Salon. Between 1882 and 1889, Claudel regularly exhibited busts and portraits of people close to her.

Romantic Torment Gets an Outlet: From the start, their romance was overshadowed by Rodin’s partnership with Rose Beuret, a working-class seamstress with whom he had been in a relationship for decades. (They would eventually marry after 53 years, two weeks before Beuret’s death.) In 1892, after years of emotional distress, Claudel put an end to her sexual relationship with Rodin, although they saw each other regularly until 1898, with Rodin offering her a modicum of financial support.

Their ultimate rupture would come in when Claudel debuted her sculpture The Mature Age. It shows a young female figure kneeling behind and clinging to an older male, who is walking ahead with an older female figure. While the sculpture was ostensibly a depiction of someone leaving behind youth for a mature stage of life, it was impossible not to see the parallels to the pair’s relationship. When he saw the sculpture, Rodin was appalled and immediately cut off his support of Claudel. He also might have had something to do with the cancellation of the commission for the sculpture.

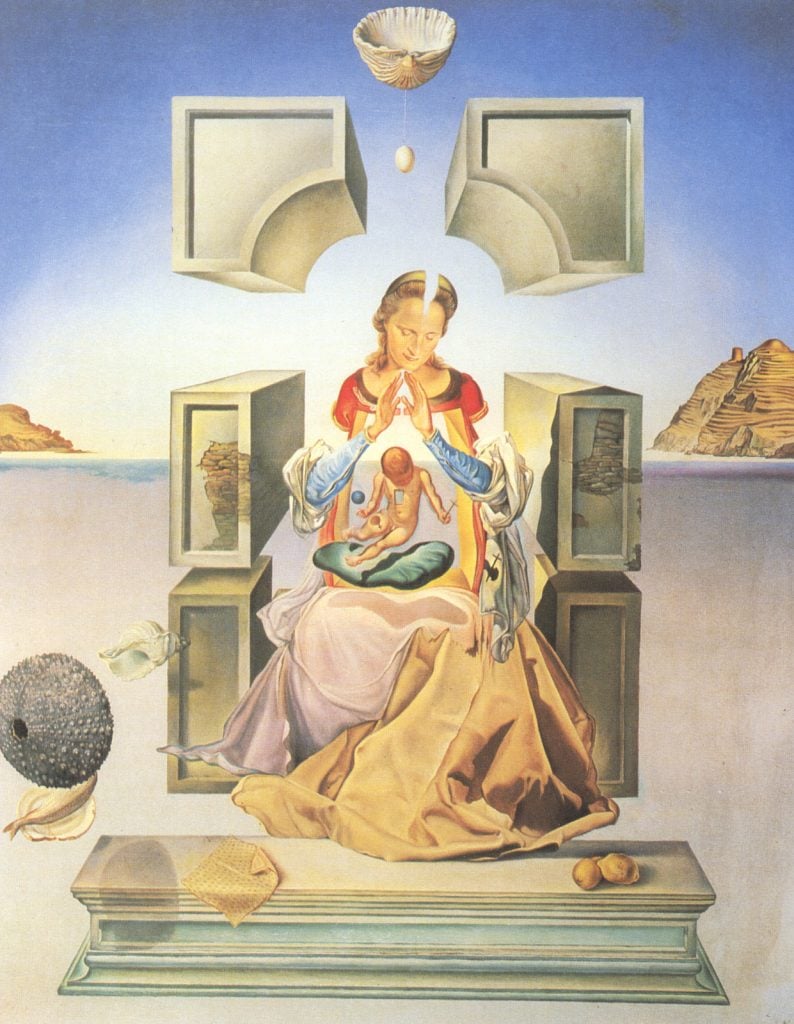

Salvador Dalí, The Madonna of Port Lligat (1949). Collection of Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

An Odd Couple: When Gala and Salvador Dalí met in 1929, they faced certain romantic obstacles: Gala (born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova) was 10 years older than the 24-year-old Salvador, and she happened to still be married to the artist and poet Paul Éluard, with whom she had a daughter. None of that deterred the young Dalí, who was wholly captivated by the Russian émigré. By the 1930s, he had begun to sign many of his works in both of their names.

Muse and Manager: Their love was as collaborative as it was unconventional. While glad to play a supporting role in Dalí’s celebrity, Gala was the managerial mind behind his success, handling his sales, exhibitions, and finances. “It is mostly with your blood, Gala, that I paint my pictures,” the artist once remarked. She often acted as muse and model, pictured famously as a Virgin Mary-like figure in his painting The Madonna of Port Lligat (1949).

Mystic Mother: “She was destined to be my Gradiva, the one who moves forward, my victory, my wife,” Dalí once said, using a term he often employed to describe Gala as a kind of mystic mother. The Madonna of Port Lligat was made in the midst of Dalí’s return to Catholicism (he even requested a papal blessing, which he wasn’t granted). Though the painting’s religious attributes are evident, the various floating emblems of the ocean (the sea urchin and shell) may harken back to the artist’s early years with Gala, when the couple lived in a Spanish seaside shack.