Museums & Institutions

16 Museum Directors Show Us the Art That Hangs in Their Offices, From Richard Armstrong’s Al Held to Zoé Whitley’s Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Take a step inside... .

Take a step inside... .

Artnet News

Call it a perk of the job.

In the offices of museum directors around the world hang some of the best paintings and prints in existence. Sometimes, they come from the museum’s collection; other times, they belong personally to the administrator. In either case, the objects that grace these spaces are rarely seen but by a select few.

We asked more than a dozen museum directors around the world to pull back the curtain and show us what they get to see every day.

Nancy Graves, White Field: To Janie C. Lee (1974). © 2021 Nancy Graves Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

My office was built to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s design in 1974, and I have tried to honor the spirit of that commission with the furnishings and art. For many years, I enjoyed Kenneth Noland’s great 1959 target Half, but when it went on exhibit in the new Nancy and Rich Kinder Building we replaced it with Nancy Graves’s White Field. While similar in scale and composition, the Graves is so very rich and rewarding, a palimpsest of maps, marks, signature scribbles, and enigmatic coded references to the work of her friends and contemporaries in the New York art world as well as the scientific advances that thrilled and fascinated her.

For me it represents a very exciting period in the history of American painting, dating from 1974, the very moment when I decided to pursue a career studying contemporary American art and architecture.

—Gary Tinterow

Mario Cini’s Portrait of Giovanni Poggi, Odoardo Giglioli, Carlo Gamba, and Nello Tarchiani (1919). Courtesy Uffizi Galleries, Florence.

To have my predecessor of a century ago, Giovanni Poggi, and three outstanding art historians and museum administrators of the past look over my shoulder at Pitti Palace while I write and sign my papers gives a great sense of institutional continuity through the ages.

—Eike Schmidt

Director Linda Harrison’s office at the Newark Museum of Art. Photo courtesy of the Newark Museum.

I choose art for my office exactly as I choose art for my home. I must want to live with it. Both at home and my office, I prefer the interest of hanging pieces salon style. I love getting lost in a wall crowded with juxtaposed objects. A way to have refreshing mini-breaks throughout a day packed with back-to-back meetings. It’s also a great icebreaker when visitors step into my office. They’re often drawn to a particular piece and thus our conversation begins.

There are ten pieces of art hanging in my office. Here are three I most look forward to seeing every day:

Hanging behind my desk is the striking BundleHouse:Borderlines #2 by Nyugen Smith (2012). Smith is a first-generation Caribbean-American artist based in Jersey City. I instantly fell in love with his work and how he approaches sharing stories through the Black diaspora.

Another piece that inspires me is Louise Nevelson’s Day Night IX (1973). When I’m stuck on a particularly thorny challenge, I look into the blackness of the sculpture and know there are endless possibilities for a solution.

Finally, Bascha Mon’s painting Dolmens-Locmariaquer (1991)—a favorite that for some reason reminds me of Big Sur on the magnificent California Coast.

—Linda Harrison

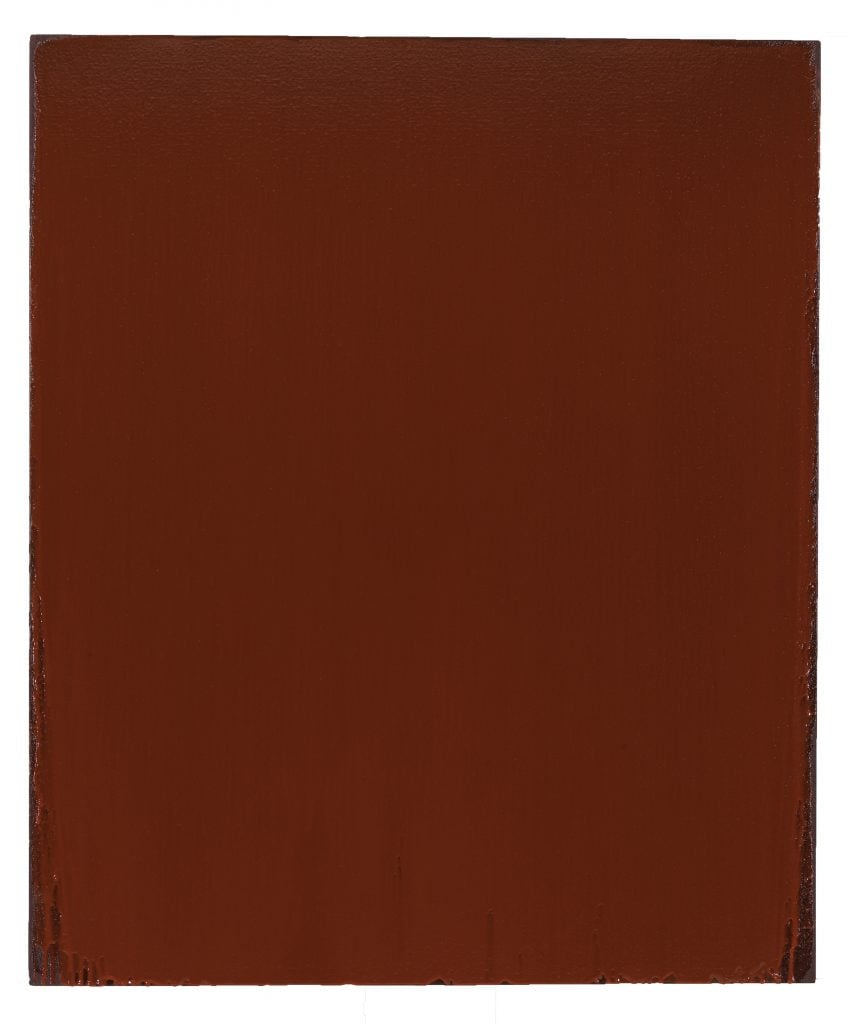

Joseph Marioni, Crimson Painting (2009). Photo courtesy of the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., gift of Wade Wilson, 2011.

It is fun for me to see Joseph Marioni’s red painting in my office. It is a beacon, summoning me back into the space after this long shutdown. It is a beacon of friendship, in that I know Joseph, and have respected his practice deeply ever since I admired his works in the eighties when I lived in Basel. It is a beacon of beauty―”liquid light” as his paintings have been called―radiant, delicate, meticulously applied layers of acrylic paint; monochrome yet richly varied in veils of translucency and opacity. It is a beacon of authority, the objectness of the painting unambiguously established through the precision of the shape of the stretcher and the exactness of the stretching of the canvas. The painting demands slow looking. It reminds me of the centrality of the artwork and the artist to our museum practice.

—Dorothy Kosinski

John Baldessari, THAT’S NOT BAD… (2015). Photo courtesy of the Broad, Los Angeles. ©John Baldessari.

The work that currently hangs in my office is That’s Not Bad… (2015) by John Baldessari. In it, Baldessari mines the relationships between images and language, a theme of his practice since the 1960s. It seems symbolic of Los Angeles, possibly a scene where people are reading scripts, and someone is giving notes. It looks like a moment of stress or conflict, which is totally undercut by the non-sequitur he places in all caps at the bottom: “That’s not bad. Like a mailman.” It’s a compelling painting, and its arch sense of the absurd reminds me of John and the many funny asides he shared with me whenever I saw him.

—Joanne Heyler

This is Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s 2012 etching, Siskin, in my office, which faces the canal. The light is wonderfully diffuse and—for any works-on-paper conservators out there—the work is never in direct sunlight!

I distinctly remember coming to Chisenhale to see Lynette’s solo exhibition “Extracts and Verses” when I was still a curator at the V&A. The V&A acquired one of these stunning etchings at the time, which I ended up writing about in the book I co-authored with Gill Saunders, In Black and White: Prints from Africa and the Diaspora. To be able to live with it every working day is a real joy and reminds me of the tremendous contemporary legacy I get to build upon here at Chisenhale.

—Zoé Whitley

I knew Juhana Blomstedt personally. We shared a deep love for Paris, where he lived for a while, and where I was born. Blomstedt’s works are among the youngest in Ateneum’s collections.

—Marja Sakari

Trevor Schoonmaker at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. Photo by J Caldwell.

I accepted the director position at the start of the pandemic and haven’t really given much thought to decorating the office. But I needed something on the wall during zoom meetings so I put up a couple of posters from exhibitions I’ve organized in the past, “Black President” and “Birth of the Cool,” two early shows that played important roles in my development as a curator. There’s also a little radio sculpture, some LPs that I’ve been fortunate to contribute to, and loads of art books.

—Trevor Schoonmaker

Portrait of Bruno Candé by Francisco Vidal. Courtesy Beatrice Leanza.

This drawing by Francisco Vidal was realized as part of his ongoing initiative to support a critical conversation around post-colonialism in Portugal, and to create new narratives that celebrate equality, inclusivity, and diversity. The portrait is of Bruno Candé, a young black actor that was murdered in Lisbon in July 2020.

—Beatrice Leanza, Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, Lisbon

In 1973, when I went to work for Al Held as a studio assistant, I sanded through two paintings in two days. It was humiliating and anger-provoking on both our sides. So I was fired.

A few days later, he called asking me to take over the desk, and act as a secretary in the studio, and I did this for next two years or so. My first exposure to the creative process in the hands of a strong living artist. It was life-changing.

—Richard Armstrong

One of the paintings I love living with in my office is Darby Bannard’s 1967 painting By the River. Bannard graduated from Princeton in 1957, one year ahead of Frank Stella, with whom he experimented with hard-edge abstraction while they were undergraduates. The painting fills the wall, enveloping us in its sunlit colors.

—James Steward

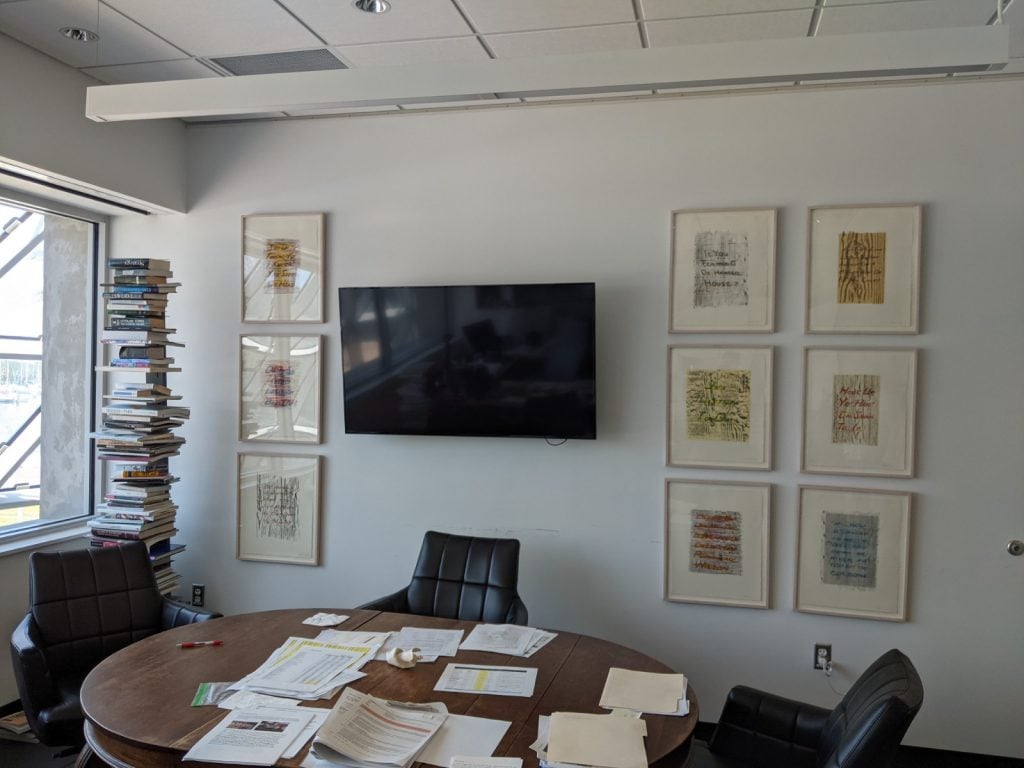

Interior view of Hank Hine’s office at the Dalí Museum with works by Ed Ruscha.

Ed Ruscha’s Sayings from Pudd’nhead Wilson, a set of ten lithographs with quotations from an enslaved character from the Mark Twain novel, and Graciela Iturbide’s Nuestra Senora de las Iguanas, a photogravure of an Juichitan woman with iguanas braided into her hair, were selected out of love and admiration.

The Ruscha work probes American identity, race, and joins language with image—as ambitious an artwork as I know. The Iturbide photograph presents the woman figure as a titan, of mythologic status, and connects us to the beauty of animals, as well.

—Hank Hine

I have long been a fan of Martin Puryear’s work, and this print is one I knew I could look at everyday and not get tired of. Sometimes I focus on the background, sometimes I see the center form in three dimensions, sometimes I notice how he has played with positive and negative space to shift the visual perspective. At first glance it looks simple, straightforward, but great artists often make work that enriches you the more time you spend with it, and this is one of those works.

—Amy Gilman

Nannette Maciejunes with the work by Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, gifted to the Museum in 2005.

In 2005, the Columbus Museum of Art nominated Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson for a YWCA Women of Achievement Award, which she won. This work of art is a thank you note to the museum, painted on deer skin paper and mailed unassumingly in an envelope. We framed the note and it has hung in this spot ever since.

—Nannette Maciejunes

Erik Neil with Michal Rovner’s Culture #4 (2003) in his office at the Chrysler Museum.

I keep a large print, Culture #4 (2003), by the artist Michal Rovner right over my desk. Many years ago, I curated a small show of her work, which I find beautiful and complex. I enjoy the multiple meanings of “culture” at play, and also relate to this image’s sense of ordered chaos.

—Erik Neil, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk

Adam Levine’s office with Alice Neel’s Nancy and the Rubber Plant (1975) and Cecilia Beaux, After the Meeting (1914). Courtesy of the Toledo Museum.

I chose works that speak to the quality and diversity of our 20th-century collection. I am particularly struck by the Cecilia Beaux work (gifted by one of the most influential people in our museum’s history, Florence Scott Libbey) and the presence of Alice Neel’s Nancy as she sits beneath her rubber plant. Gustaf Fjaestad’s Silence – Winter (1914) behind my desk was a perfect winter selection for our world of Zoom meetings: an immersive winterscape reminding us of the world outdoors.

—Adam Levine