Art World

Inside the Art Preserve, the Soon-to-Open Museum Dedicated to Showing How Significant Artists Lived and Worked

Located in Wisconsin, the Preserve has an unconventional approach to preserving and presenting art.

Located in Wisconsin, the Preserve has an unconventional approach to preserving and presenting art.

Rain Embuscado

Collecting art is risky business. But preserving art is on a level all its own.

This was the biggest takeaway following a recent, socially-distant tour of Wisconsin’s new Art Preserve. Situated a short five-minute drive southwest of Sheboygan’s historic downtown, the colossal structure, designed by the environmentally-conscious architecture firm Tres Birds, is the culmination of a Kohler family heiress’s passion project, nearly fourteen years in the making. Now, after surviving a few pandemic-driven setbacks, the Preserve is revving up for its grand opening in late June.

Home to a formidable 25,897 art objects by some 180 artists, the Preserve is, by all accounts, a crowning achievement in the late Ruth DeYoung Kohler II’s career as both a local arts organizer and as a midwest community leader. Construction began in earnest in 2016, when Kohler stepped down as director of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center (JMKAC) to focus on the Preserve full-time.

Exterior view of the Art Preserve in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Photo by Rain Embuscado.

To date, JMKAC’s Art Preserve has expanded operating costs to $1.6 million a year—the lion’s share of which is funded by the Kohler Foundation, Inc. along with a small group of individual and corporate donors. Beyond the building, the Preserve extends its institutional support to a number of sculpture gardens and cultural sites across the region.

But its distinguishing speciality is the presentation of “artist-built environments.” This curatorial mission is ambiguous enough to encompass “spaces and places that have been significantly transformed by an artist,” and derives from Kohler’s decades-long affair with preservation initiatives.

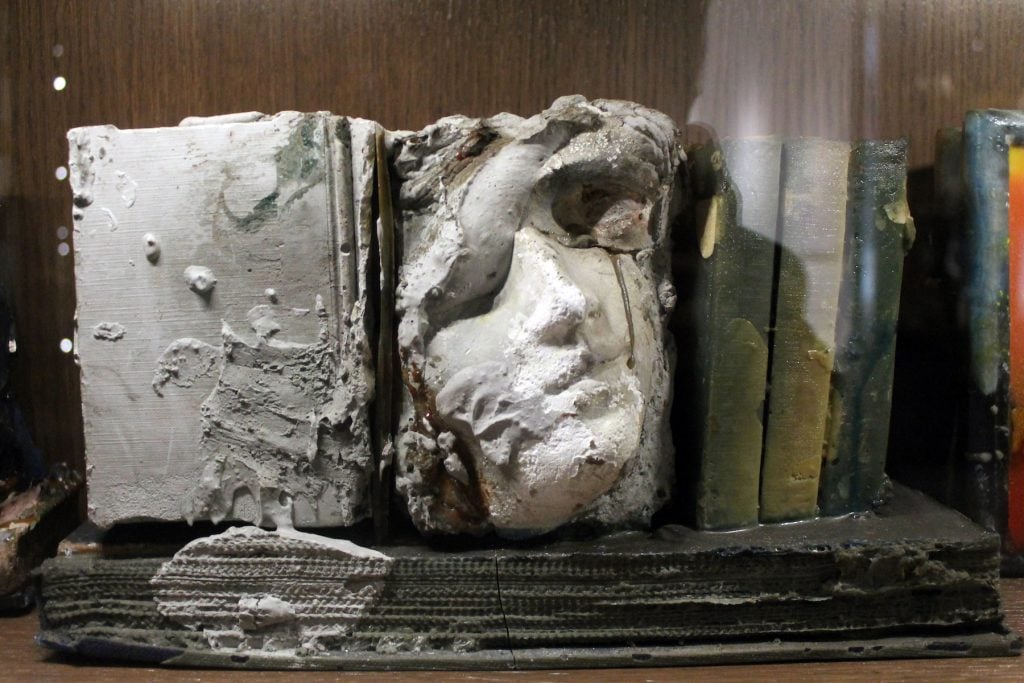

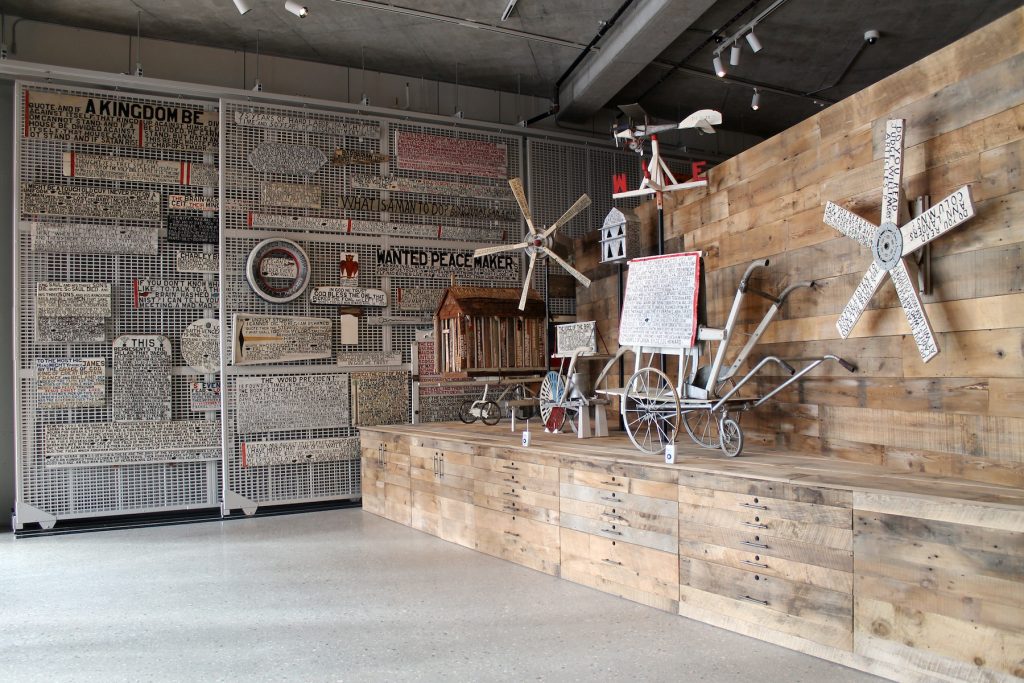

Installation view of Ray Yoshida’s personal collection at the Art Preserve in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Photo by Rain Embuscado.

The works on offer are distributed across three floors, each organized around themes of location and relations between figures. The environments run the gamut from a display of all the little knickknacks an artist collected throughout their lifetime to entire oeuvres to full-on one-to-one recreated versions of studios.

While as a whole the Preserve registers a bit like an arbitrary collection of estates—albeit with a few thoughtful through-lines unifying them—the installations definitely yield nuanced glimpses into the lives and work of the artists represented.

JMKAC’s associate director Amy Horst, who has been with the organization for sixteen years, told Artnet News in a Zoom interview that acquisitions were invariably spurred by sudden and serious practical needs on the part of the artists or their families.

A popular story among the JMKAC’s staffers recounts Kohler’s timely 1983 acquisition of 6,000 art objects produced by native Wisconsinite Eugene Von Bruenchenhein—an artist who, until recently, did not command the art world influence to secure his estate. The Art Preserve’s associate curator, Laura Bickford, told Artnet News that in addition to delivering Von Bruenchenhein’s body of work from uncertainty, Kohler’s decision also created an opportunity to support Von Bruenchenhein’s wife, Marie.

Saving estates in dire straits happened to be Kohler’s thing. Fred Smith, another Wisconsin-based artist, had assembled over 230 concrete sculptures around his home by the time of his death in 1976. In what would be Kohler’s first preservation effort and acquisition through the Arts Center, the site was spared with the coordinated effort of local community leaders.

Installation view of Nek Chand’s “Rock Garden” sculptures at the Art Preserve in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Photo by Rain Embuscado.

Similar acquisition stories applied to a suite of Nek Chand’s “Rock Garden” sculptures, Loy Bowlin’s Beautiful Holy Jewel Home, and the personal effects and collections of Lenore Tawney (which, at the time of my visit, had not yet been installed).

The greater bulk of the Preserve’s holdings comprise mostly unknown, self-taught, and outsider artists. Emery Blagdon’s Healing Machine, for example, was little more than a local legend in central Nebraska. Blagdon’s dazzling kinetic assemblages, made of minerals, sheet metal, magnets, and other mechanical odds and ends, had previously been housed in a nondescript shed in Stapleton, Nebraska. Within the formal context of the Art Preserve, Blagdon’s work gains a kind of institutional recognition that would have been otherwise unavailable to him.

“Kohler really was moved by artists, and by things that brought awe and wonder,” Horst told artnet News. “The Art Preserve was just a natural extension. The decisions that have been made for the Arts Center have not been made in line with art market ideals.”

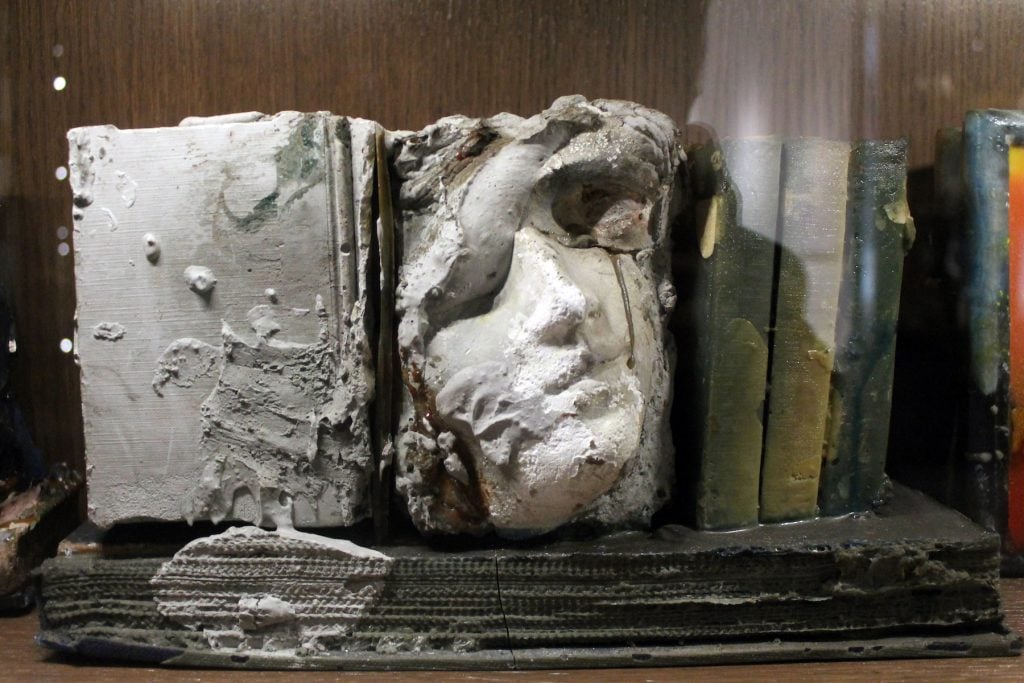

Installation view of Frank Oebser’s Little Program at the Art Preserve in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Photo by Rain Embuscado.

Wisconsinite Frank Oebser, whose mechanized marvels occupy a corner of the first floor, spent his twilight years animating larger-than-life-size sculptures of cows, scarecrows, and birds in the barns and sheds of his family’s dairy farm. In an operation he dubbed his “Little Program,” his creations could jingle, rattle, and shake for curious visitors with the push of a button.

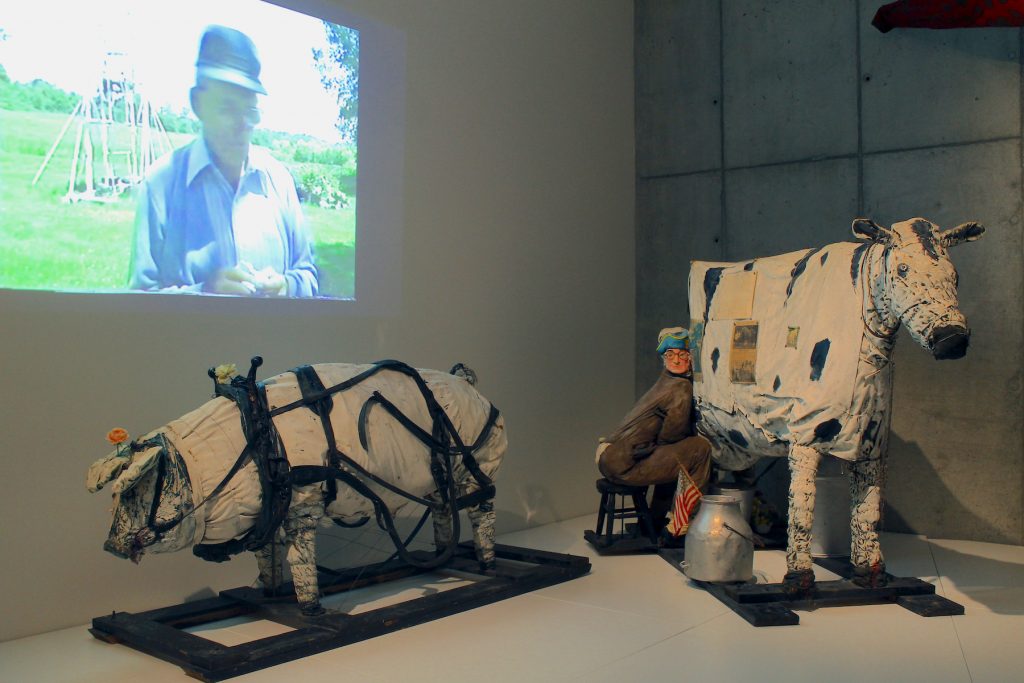

Installation view of select works by Jesse Howard at the Art Preserve in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Photo by Rain Embuscado.

Oebser didn’t consider himself an artist. Neither did Missourian Jesse Howard, who articulated his thoughts on everything from local politics to Bible verses of the day on practically any surface he could find. (Ray Yoshida, a prominent mentor of the Chicago Imagists, happened to own a work by Howard—and the connection is emphasized by their respective exhibitions’ proximity on a floor of the Preserve.)

“If you look at the history of exhibitions at the Arts Center, it’s been giving a voice to [artists] who don’t have voices in institutions,” Horst told Artnet News, explaining the focus on self-taught figures.

View into the preservation lab at the Art Preserve in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Photo by Rain Embuscado.

For a place like Sheboygan, where deep political and cultural divides are palpable in a population of 48,000, the distinction between professional and vernacular or insider and outsider doesn’t really seem to matter. In fact, Horst explained that the JMKAC and the Art Preserve have been attempting to leverage their platforms to unify the public around shared values.

“We have to acknowledge our community,” Horst said. “While the majority of the content creators at the Arts Center are liberally-minded, we make sure we’re out in the community communicating with and understanding where the community is, and finding opportunities for our community to see each other and other ways of being inclusive and equitable.”

Building bridges between disparate realms is no easy feat—but this, perhaps, will be Kohler’s enduring legacy.