When I moved apartments a couple of weeks ago, I couldn’t help but admire a tattoo on one of the movers. His name was Joey Rosado, he told me, and he had previously worked as a tattoo artist. Rosado, who is 32, was back at Brooklyn’s Sven Moving, where he had worked before completing his tattooing apprenticeship, while the studio where he worked, Chinatown’s No Idols Tattoo, was closed.

Rosado’s situation isn’t unique. As the coronavirus pandemic swept across the US, many artists and other professionals in the industry found themselves turning to essential work to keep financially afloat.

Across the country in Seattle, curator John Wesley, who is 36, was expecting to celebrate the opening of his new art gallery this past spring. Instead, he found himself taking a janitor job at Whole Foods, before transitioning yet again to running a food bank.

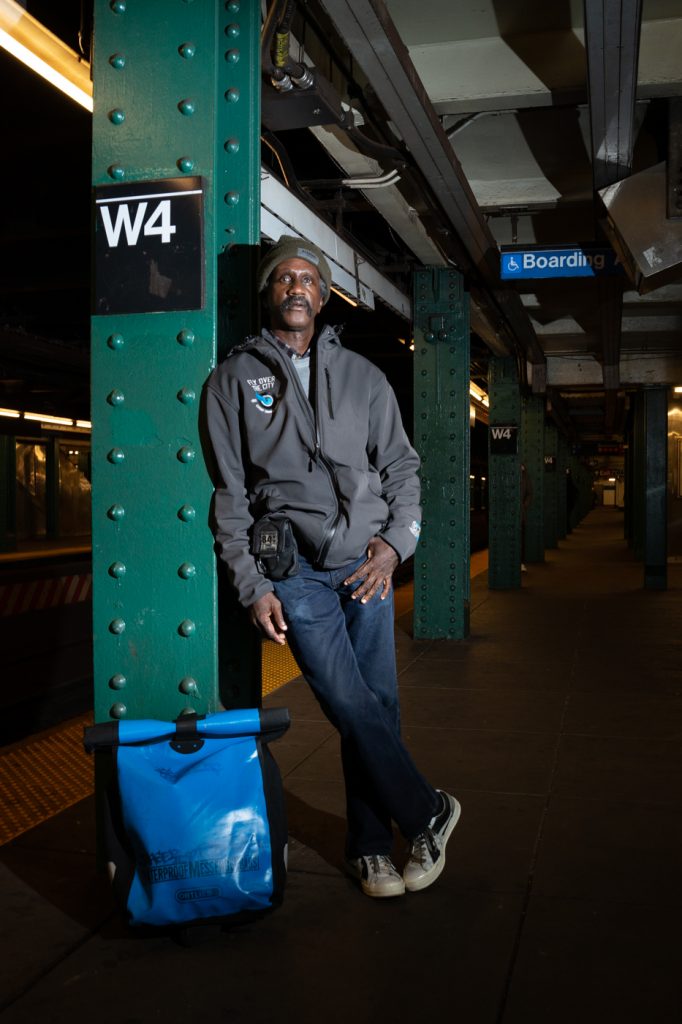

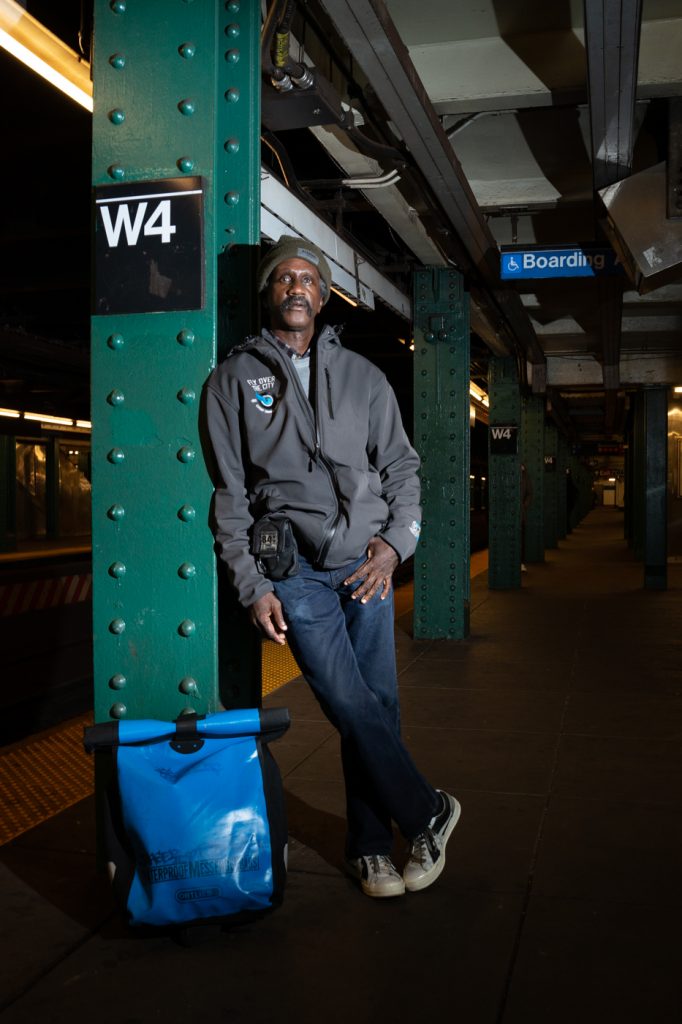

Newark street photographer Kurt Boone has moonlighted as a foot courier, a job now considered “essential,” for 20 years. But even that experience didn’t prepare him for working in the age of coronavirus. “I’ve seen the city in crisis numerous times. But people are dying every day out here. This is serious stuff,” Boone told Artnet News. “As a street photographer, I’m documenting it because that’s what I do, but it’s tragic on a lot of levels.”

Photographer Kurt Boone working as a courier during the coronavirus pandemic. Photo by Nick Sansone.

Individual Challenges

The professional situation that each worker finds himself in comes with personal tolls too.

“I’d been wanting to tattoo since I was a little kid. It was a dream job,” said Rosado. “It was pretty heartbreaking that I wouldn’t be able to do something that I worked my whole life for.”

The tattoo industry won’t be able to resume business in New York until the beginning of phase three of the reopening. Even then, customers will need to prove that they’ve tested negative for the virus, and have their temperatures taken. Everyone will wear masks, and there will be protective barriers between stations. But the shutdown’s effects have already been devastating.

Joey Rosado tattooing. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“New York tattooing is screwed,” Rosado said. “Some shops have closed permanently. Some of the tattoo artists I know have gone to other states to guest spot because they can’t afford to stay here.”

Meanwhile, the Square, the gallery and co-working space Wesley had founded with Kymani Thomas, was set to open in April, until the outbreak hit. “We cried innumerable tears,” Wesley said. “We had both dropped every single thing that we were working on and every other thing that was generating us money and put all of our time and all of our money and all of our heart into the gallery.”

Still, he managed to make some art sales even while working at Whole Foods. “I actually sold a painting from the restroom, while I was cleaning,” h said. “Someone DM’d me ‘I’m interested in this painting.’ I sent them the info and I sold it right there!”

Curator John Wesley hanging ART PROM, a painting by AFRO SPK, at an art and fashion event in 2019. Photo by Yanina Sokolovska.

Boone, who is 60 and suffers from a chronic lung condition, has been worried about how working would increase his risk of exposure to the virus, but felt he had no choice. “If I lose my savings, I have nothing else—I’d be homeless,” he said.

But he’s not earning much of a living at the job these days either. A dramatic decrease in the number of jobs booked, led to his courier income falling from between $300 and $400 a week a month ago to just $50.

Joey Rosado on the Sven’s Moving truck with two of his coworkers. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

New Beginnings

Wesley’s six-week stint at Whole Foods ended on a sour note, but he decided to stay involved in the food industry in a new charitable role. Inspired by his parents, who ran a food bank when he was a kid, and his friend, artist Keli Lucas, who has turned her Brooklyn gallery into a food bank, Wesley formed the nonprofit Seattle BIPOC Organic Food Bank.

The project aims to ensure access to clean water and organic food for every person in Seattle, and will purchase CSA boxes from farms and distribute them to community members in need. So far, Wesley has raised over $40,000 for the cause on GoFundMe.

He also still plans to open his gallery. “The art gallery is the administrative and cultural and spiritual center of the food bank,” Wesley said. “We can still make art and we can still support the artistic community, but we have to feed people too.”

Kurt Boone has photographed New York during the pandemic, including homeless people on the subways. Photo by Kurt Boone.

“The pandemic was the first time that a lot of middle-class and upper-middle-class people started feeling like ‘Hey, ‘I too am vulnerable,'” Wesley said. “We have to build models where we can rely on each other, because we can’t rely on jobs, corporations, or the government.”

The past few months have also been eye-opening for Boone, who has been photographing some of the homeless people on the subway, and otherwise documenting the lockdown. “I would not have had those images if I wasn’t an essential worker. I wouldn’t have been out there,” Boone said. “The whole city shut down. I’d never seen anything like that.”

The Photography Collections Preservation Project is working to get Boone’s work into permanent collections like those of the New-York Historical Society, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the National Museum of American History. He will self publish his latest book, Aerosol Culture: A Day at Graffiti Hall of Fame, next month.

Kurt Boone has photographed plywood barriers covered in graffiti during the George Floyd protests in New York. Photo by Kurt Boone.

Rosado, meanwhile, has developed a new artistic practice after he figured out that he could load a pen into his tattoo gun and draw in a pointillistic style. “I’m also drawing flash to have stuff prepared for when I get back,” he said. “I have a bunch of ideas that I want to do that are inspired by the pandemic and everything that’s going on with Trump.”

Despite the lip service paid to essential workers in the news, Rosado, Boone, and Wesley all said they don’t always feel customers appreciate the risks they’re taking while on the job. “The media has tried to give us respect, but on the ground, not so much. Making my deliveries, I wasn’t getting tips or any extra thank you’s,” Boone said. “I’m used to it. I block out all feelings when I’m on the street—if I look to get respect, I’m going to hurt myself.”