Art History

Why Narrative Art Speaks Louder Than Words

Filmmaker George Lucas is building a museum of narrative art. But what is this genre exactly?

Most people know George Lucas as the writer-director of the original Star Wars trilogy, as well as a producer of many films and series that make up the franchise’s extended universe. In recent years, he’s also been working on building a museum in Los Angeles, which is set to open in 2026.

As its name suggests, the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art will be dedicated to collecting and showcasing the narrative art form across fine art, photography, comic art, and illustrations. Already in its collection are works by artists ranging from Judy Baca and Diego Rivera to Norman Rockwell. The diverse line-up hints at the sheer breadth of narrative art, which can boast a history that matches that of art-making itself. Here, we unpack its what, when, and how.

Photo: Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times via Getty Image.

What is narrative art, anyway?

Narrative art can be loosely defined as art that tells a story. These visual representations can come from religion, mythology, history, literature, current events, or even personal experience.

No two pieces of narrative art are the same. While some depict entire stories from beginning to end, others focus on a specific scene that, in the eyes of the artist, encapsulates what the underlying story is about. Most narrative art, like most narratives, contain norms, values, and lessons that reflect the culture and time period of the artist.

When and where did narrative art originate?

Some argue that narrative art emerged with some of the earliest known cave paintings. This is a contested view, since it’s virtually impossible for us to know whether these paintings functioned as illustrations of specific events or oral traditions.

The Narmer Palette. Photo: Amir Makar / AFP via Getty Images.

One of the oldest works of art depicting a known narrative is the Narmer Palette, a gray-green siltstone slab from the 31st century B.C.E. that shows the eponymous pharaoh unifying Upper and Lower Egypt, donning two crowns, and marching in a victory procession under the watchful eye of Hathor, goddess of the sky, women, fertility, and love.

Are there different types of narrative art?

Just as there are different types of narrative, so too are there different types of narrative art. Although classifications are continuously debated, art historians generally distinguish between narrative art that’s monoscenic, continuous, synoptic, panoptic, progressive, and sequential.

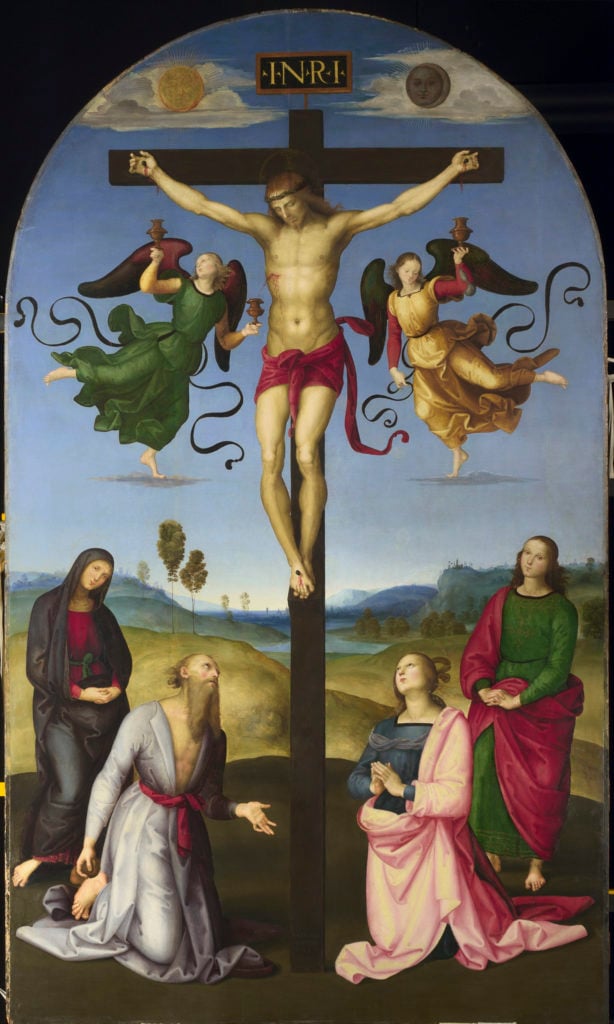

Monoscenic narrative art depicts a single scene as opposed to an entire story. Usually, artists select what they view as the important part of a story, such as the climax or inciting incident. A well-known example of monoscenic narrative art is the Crucifixion—Christian religious art that depicts the death of Jesus.

Raphael, The Crucified Christ with the Virgin Mary, Saints and Angels (The Mond Crucifixion) (ca. 1502-3). Photo: The National Gallery, London.

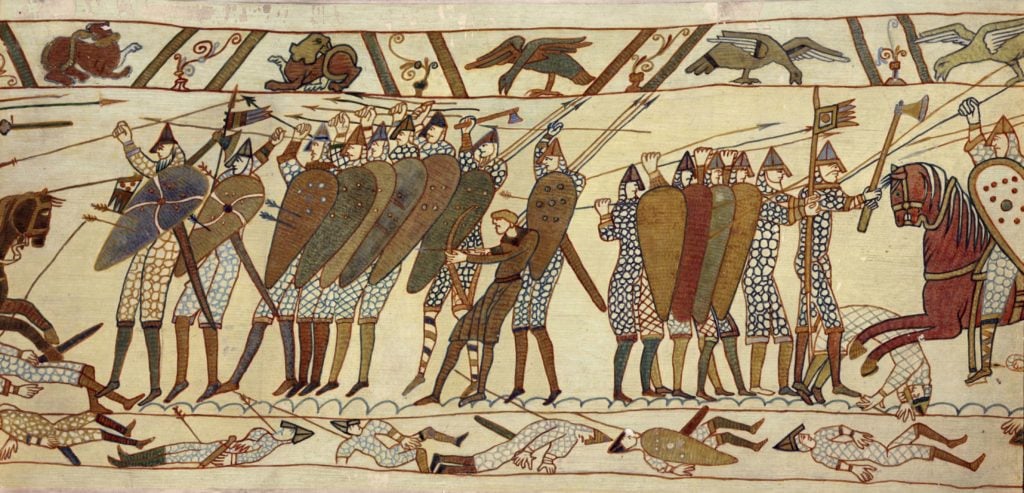

Continuous narrative art depicts multiple scenes from a story in a single frame, allowing viewers to read the artwork as they would a text. Examples range from classical antiquity, such as Trajan’s Column in Rome, a memorial that recounts the Dacian Wars, to the early medieval Bayeux Tapestry, which, save for at least two missing panels, depicts the Norman Conquest of England.

A section of the Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered cloth 231 feet long depicting the Norman Conquest of England and the Battle of Hastings. Photo: Spencer Arnold/Getty Images.

Synoptic narrative art, like Lorenzo Ghiberti’s bronze relief The Creation of Adam and Eve, The Temptation and Expulsion from Paradise, shows the same set of characters performing different actions without a clear sequence, while panoptic or panoramic narrative art, such as the marble friezes of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, depicts a clear sequence of actions without repeated use of the same characters.

Lorenzo Ghiberti, Creation of Adam and Eve (1425-1452). Photo: Getty Images.

Progressive and sequential narrative works of art are relatively modern creations, closely associated with early French and Swiss comic artists like Rodolphe Töpffer. Unlike continuous, synoptic, or panoptic narratives, the individual scenes of progressive and sequential narratives are meaningless on their own, and have to be viewed in succession for the tale to be fully appreciated. Sequential narrative art is virtually identical to progressive narrative art safe for one crucial difference: the inclusion of frames or, in comic-book speak, panels.

It’s important to remember that these classifications are not mutually exclusive, and that certain works of narrative art borrow elements from two or more.

Who are some of the noteworthy creators of narrative art?

One of the greatest narrative artists in history was the 17th-century Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn. Rembrandt was a Baroque painter, part of art movement that emerged after the Renaissance. Baroque art is characterized by elaborate compositions and exaggerated gestures reminiscent of theatre, which Rembrandt studied to improve his own storytelling abilities. These are on full display in his 1636 painting Susanna, which depicts the Biblical heroine at the moment she is discovered in a compromising position by two men intent on abusing her.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Susanna (1636). Photo: Mauritshuis / Rembrandt House Museum.

Another noteworthy example by one of the great practitioners of narrative art is French Neoclassical artist Jacques-Louis David’s 1787 painting The Death of Socrates, which depicts the Greek philosopher at the moment he is about to commit suicide at the order of the state. Reaching for a goblet of hemlock, Socrates uses the occasion to teach one final lesson to his loyal students: that death is not to be feared by the philosopher. In the corner of the composition sits a figure thought to be Plato, who recorded Socrates’ life in writing.

Is narrative art still popular in the 20th and 21st centuries?

During the late 19th and early 20th century, the advent of photography motivated visual artists to experiment with form and color as opposed to subject. Abstract art doesn’t tell stories so much as it makes statements about what can and cannot be considered art, and how meaning is created in the eye of the beholder.

That’s not to say narrative art disappeared completely. In fact, some of the great photographers of the 19th and 20th centuries have used their art form to tell stories, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, who sought to capture the “decisive moment” in his photographs.

And look at the paintings and illustrations that will be featured in Lucas’ museum, like those by Norman Rockwell, Diego Rivera, and Judy Baca.

Though his work is sometimes rejected as kitsch, Rockwell was a masterful illustrator whose images tell elaborate if highly romanticized stories about ordinary people, including families, friends, and groups of workers. His 1943 work Freedom of Want shows the Platonic ideal of a Thanksgiving dinner, but also comments on the Second World War, illustrating one of President Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms, articulated in his 1941 State of the Union address—freedom from fear, freedom from want, freedom of speech, and freedom of worship.

Norman Rockwell, Freedom From Want (1943). Photo: Norman Rockwell Museum Collections.

Mexican artist Diego Rivera is best remembered for his sprawling murals, many of them illustrations of major political events like the Mexican Revolution or the Bolshevik Uprising. His 1931 painting Agrarian Leader Zapata lionizes a Mexican revolutionary leader who fought not for power or prestige, but for the autonomy of his small agrarian community in the state of Morelos.

Diego Rivera, Agrarian Leader Zapata (1931). Photo: Collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Baca is best known for her Great Wall of Los Angeles, a 13-feet-long mural in the San Fernando Valley that recounts the entire history of the state of California through a BIPOC, feminist, LGBTQ lens, moving from Indigenous history to colonization to the arrival of Jewish refugees, the economic hardship of the Dust Bowl, the internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War, and the Zoot Suit riots, among many other events.

Judy Baca, La Memoria de Nuestra Tierra: Colorado (1999), detail. Photo: SPARC Archives/SPARCinLA.

These and other important examples of narrative art take part in what could be classed as revisionist histories—retelling history in a way that emphasizes the voices of racial and ethnic minorities, for example Jacob Lawrence’s works that depict the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to the North.

Looking back even further in history, we could consider Robert Colescott’s painting that lampoons Emanuel Leutze’s great canvas Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), depicting the Revolutionary War; Colescott’s painting George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook (1975) ingeniously and hilariously puts the Black inventor in place of the first American president, elevating African American histories to the same level as those of white people (the painting is featured in the Lucas Museum’s collection).

As history continues to unfold, one thing is for sure: narrative art will continue as a vital art form, with more and more stories to tell.

For as long as there has been art, revolutionary movements have continually reshaped its creation and perception. Artcore unpacks the trends that have shaken up today’s and yesterday’s art world—from the elegance of 18th-century Neoclassicism to the bold provocations of the 1990s Young British Artists.