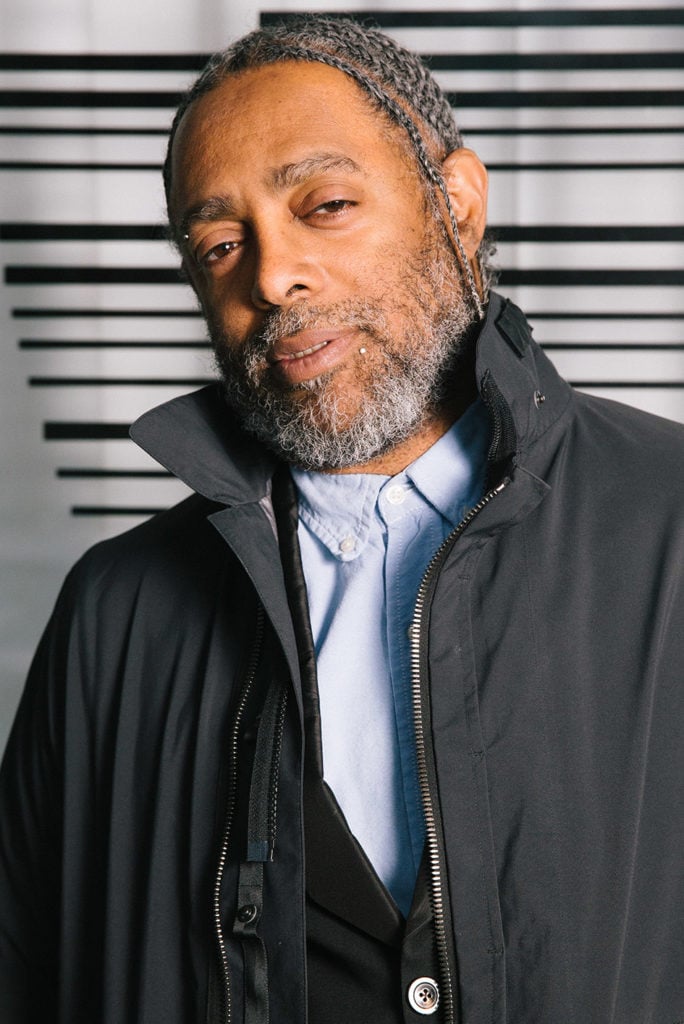

People

‘Black People Figured Out How to Make Culture in Freefall’: Arthur Jafa on the Creative Power of Melancholy

The American artist talks Basquiat, Kanye, Oprah, and the Dana Schutz controversy.

The American artist talks Basquiat, Kanye, Oprah, and the Dana Schutz controversy.

Kate Brown

A massive Confederate flag hangs in front of a smaller United States flag, both dyed black, the star spangled banner trumped. One wishes it was the other way around but it isn’t, and this is exactly Arthur Jafa’s point.

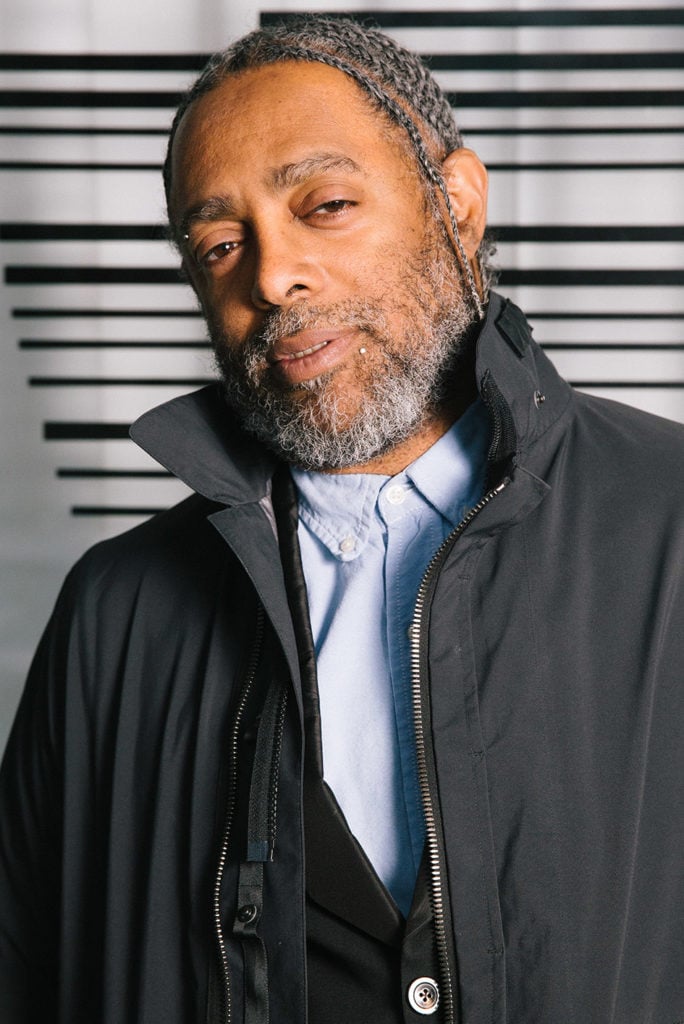

In Jafa’s exhibition-meets-video installation A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions at Berlin’s Julia Stoschek Collection, the 57-year-old US artist radically recontextualizes historical narratives of blackness. His searing works feature sequences of footage from segregation-era America to Jimi Hendrix guitar solos and African Fang masks, peppered with brutal crime scenes from racially-provoked murders. Cut to the singer Nina Simone, a still from Ridley Scott’s Alien, and then Mickey Mouse, here an all-black character, his white mask removed.

The gesture is something that Jafa describes as “affective proximity.”

Jafa shared the recurring question in his practice at the press conference before the show opened on February 11: How does one make art that has the power, beauty, and alienation of black music? And how would it be if black people were loved as much as black music? In fact, making music, he said, is the only place one can be black “without being marginal.”

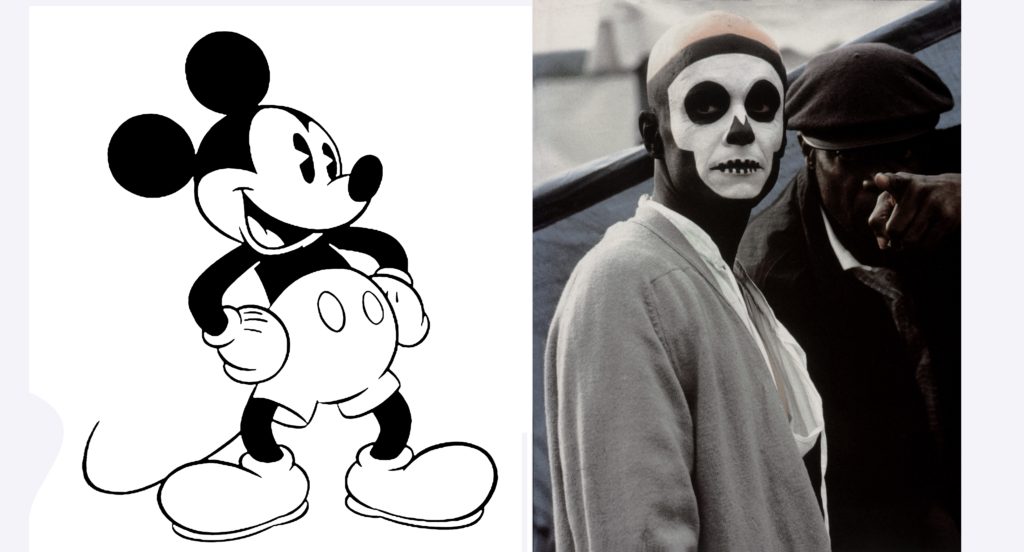

Music is deeply intertwined in Jafa’s life and work. Some weeks before the opening, he was in Berlin in the production studio with Kanye West. Music permeates the spirit of his sculptures, his large-format photoworks, and his collaged films. Take the 2013 film and sound installation APEX: It’s an explosion of rapid images set to an aggressive techno track by DJ Robert Hood. Images pulse by in alternating scenes of absolute horror, science fiction, and fashion. It moves too fast to fully grasp, but this is the desired effect. It leaves an impression instead that is gut-wrenching, picturesque, unforgettable, and totally real.

Arthur Jafa’s Mickey Mouse Was a Scorpio (2016). Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise.

Jafa’s installation in Berlin has traveled from London’s Serpentine Galleries, where it was co-curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Amira Gad. The show also features work by Norwegian artist Frida Orupabo and New York-based photographer Ming Smith, who Jafa invited to collaborate with him.

The re-tweaked exhibition in Berlin comes amid a refugee crisis overwhelming the continent and angry nationalism. It comes as nations finally cracking open the door on their dark histories of colonialism and the restitution of African artifacts. And it comes, of course, as the world watches America in what seems to be a resurgent civil rights movement.

Nothing has been seen in Germany quite like this before. It’s definitely uncommon to see artistic representations of the Nazi salute outside of historical museums, but here in Jafa’s multi-room exhibition, there’s a massive photograph of a hundred black school children with their hands raised in salute. The image was taken in Virginia around the time of the Civil War.

artnet News spoke with Jafa about identity politics, the Dana Schutz controversy, being mistaken for Jean-Michel Basquiat at Gagosian Gallery, and his doubts about Oprah Winfrey’s White House potential.

Still from Arthur Jafa’s APEX (2013). Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise.

There is less awareness in Europe about its role in the slave trade than there is in North America, where the conversation is in a much more advanced place. Did that change your approach to this exhibition?

I am not trying to adjust what I’m doing for one context or another. I have certain romantic ideas about Berlin that are more connected to art and music, and how techno was received there in the ’80s and ’90s. I was always intrigued by the proposition of black artists operating in Berlin.

To me, the question is not to try to tweak the work to have a specific effect, but rather to let the work be itself and see what the effect is. Often, I’ve used my work as a primal site for the introduction of black African artifacts into the West, and all the implications of that—the cascading effect that was caused by philosophy, art aesthetics, phenomenology. In a sense, the African artifacts functioned as a kind of precursor to black bodies actually being living and active bodies in the West. I have always been really interested in that: The African artifact as a radically alienated artifact. I am trying to make the blackest, most alienated work possible and see what happens when you drop it into a different context.

Very early on when I first had conversations with the Julia Stoschek Collection, there was a little back and forth: They wanted it to be a good show. I don’t want it to be a good show, because I’m not trying to operate inside of a frame of “good” or “bad.” It’s really not what I’m actively interested in. I said, “disabuse yourself of that; we’re not going for ‘good’ here. Whatever that might be, we’re not going go for it.”

This exhibition comes at a time when there are heated debates about who gets to represent what. In terms of your success and your practice, how do you feel about the discussion around identity politics?

I’m not even sure I completely know what it means. Honestly, my mind falters in the face of the term. It fatigues in the face of the term. I kind of just don’t care. But I don’t like either/or answers.

I’m sort of at war with linear thinking. What I mean by linear thinking is not so much like linear versus non-linear. I mean the tendency to have narrow relationships between two things. For example, “I am a black man, so if I become president I am going to be good for black people.” Or, “I am a black person, so I make black art.” I try to avoid that.

It’s a profound conundrum for human beings, that the basis of a lot of our problems are caused by associative thinking. People project things onto you based on what they assume you might be, tethering you to all these kinds of associations. That’s the worst kind of thinking, but what’s so paradoxical about it is that it’s also the basis of human intellect. You can’t get rid of associative thinking. I think it’s important for us as individuals and as aggregate individuals not to resist associative thinking, but to resist the conclusions drawn.

The issue is not to stop being black or trans or female, or whatever you are, just so that you can be seen as a human being. The issue is to be what you are: black and trans and female and all the other qualities that you are, and not just assume them but assert and demand that you are given the same privileges and leeway as any other legitimate human being, as a fully vested subject.

Arthur Jafa’s APEX (2013). Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York City, Rome.

Speaking of techno, your films feature the music heavily, and you also cut and layer images together in a way that I relate to techno as well. Can you expand on your interest in that?

It’s like club music to me. Techno, which I love obviously, I see as being a very specific product of Detroit and black people’s relationship to technology, because we were the first technology. We are the technology that drove the American industrial engine. Our relationship to technology is very particular. What I would say is that club music—of which techno is a part—is DJ-based music. It’s not instrumental. The mix is it. The mix is in the face of linear thinking, it is in opposition to reductive thinking.

What do you hope people get out of your work?

I have sometimes said that I want to produce a work that has a kind ontological integrity, such that its “thing-ness” is indisputable. I’m less interested in making art and more interested in making things. Things that have a certain power and a certain kind of resilience. When people look at things, those things are worn down by the gaze. So how do you make a thing an artifact that can resist that wearing away that happens, when it’s constantly being bombarded by the gaze, specifically the white gaze. How does a thing maintain its integrity in face of the white gaze?

Speaking of the white gaze, how do some of the ideas you have shared about black cinema and the gaze connect to painting? I am wondering your thoughts on the Dana Schutz Open Casket controversy, for example. Schutz said she related to the image of Emmett Till as a mother—Was this the wrong thing to say?

“Wrong” in regards to the fact that she got her ass kicked. It seemed completely legitimate to me. But again, there are some skirmishes that I am not trying to get into because some of those skirmishes can’t be resolved in a debate. People are in different places.

I have always been somewhat perplexed by the fact that Dana Schutz is getting her ass kicked for her work, but my work is completely full of black people getting killed. Violence against black people is a very prominent aspect in a lot of my work. Is it simply because I am a black man that I get to say that? On a certain level, that’s a little problematic to me. If I want to say something about someone who is trans and I am not trans—first of all, I am a libertine, so I’m going to do what I want to do and I am prepared to fight motherfuckers about it—it can’t be so reductive as that. It doesn’t seem like that’s the way to go forward. It’s too reductive. Do I think the history of black representation or white representation of black people is fucked up? Absolutely. But I’m not prepared to have anybody say that I can only make films about black people.

The Dana Schutz issue was interesting to me. Henry Taylor had a painting of Philando Castile in the same show and no one said anything about it. In the instance of Philando Castile, he was murdered and he, in a way, wasn’t consensually taped. His girlfriend was just filming him. Emmett Till’s mom actually put him on display. One could argue that her doing that already moves it into the realm of an image that is circulating and is intended to circulate in a certain sense. I get why Schutz didn’t defend herself. People were talking about burning paintings. Even if you want to go down that road, there are about a billion other things you should burn before we get to her painting. A whole bunch of cinema, a whole bunch of shit. If you even buy into that logic, Schutz’s painting would be so far down the list of things you want to destroy. You wouldn’t get to it in a hundred years.

Arthur Jafa’s APEX (2013). Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York City, Rome.

You also spoke about melancholia and success with regards to Jean-Michel Basquiat, who you knew personally. Was he depressed by the success that he experienced?

He was very happy about the success, but he was depressed because he won the lottery and it didn’t change his life. He achieved a lot of his goals, but not his objectives. Strategically, he got placed in this collection, that gallery, and this magazine, but that was not happiness and it didn’t offer the solution that he thought it was going to offer. It didn’t offer the antidote.

Do you remember the first time you heard about Basquiat’s work?

I remember around the time. I think I might have seen something in GQ, strangely enough. It wasn’t a picture of him, but a drawing. It was fierce. It was electric.

Did your reaction have anything to do with seeing a black artist featured in a magazine then?

It wasn’t like I looked at it and thought, “that’s a black man.” So many of the figures in his work are black in a cultural sense, but they are not black figures in the sense of a rendering of a person. Most of them are skulls from Grey’s Anatomy and his work is very voodoo. I saw it and I recognized the energy of it. It could have proven to be the work of somebody who wasn’t black, but I saw that reproduction and I think it had a blurb that said “…a young black artist…,” or something like that. So yes, but I didn’t even see him.

Later I read about him and his first show in Los Angeles. It was at Larry Gagosian, which was then a tiny little gallery. I was on my way back to New York from visiting some friends in LA, and I was curious to see this stuff in person. I was flying out on Friday and the show opened on a Saturday or something, so I just drove down. I was walking around and this white lady came up and started talking to me in a way that I just wasn’t used to. She was being super casual. Then she asked me if I wanted to have dinner. The guy who was installing nearby burst out laughing and she was confused. She said, “Is this not the artist?” What other reason could there be for a young black man with his hair uncombed to be standing in a gallery? I think I met him six months after that.

Arthur Jafa’s APEX (2013). Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York City, Rome.

As an artist who thinks a lot about black cinema, I wonder what you make of a televised spectacle like the Grammy Awards?

I don’t have an opinion about it. I didn’t see the Grammys not because I was protesting it, but because I wasn’t interested. I was hanging out with Kanye West in Berlin when the Grammys were happening. I’m not going to be in my room watching the Grammys when Kanye is downstairs recording.

My brother told me the media were making a big deal that Kanye wasn’t at the Grammys, that he was hanging out in Berlin. There was a picture of him hanging out in a restaurant by himself. It gave this vision that he was here being depressed. It’s so misleading.

I’m sure you heard about Oprah’s speech. What did you think of the reactions to it?

Oprah for president? Maybe, but we should already be disabused of the idea that if we put a black person into office it’s going to fundamentally change anything for black people. We just did that and it didn’t fundamentally change anything for black people. People talk about Black Lives Matter, which is a response to black people being wantonly shot like dogs in the street, as if that came up under Trump. That came up under eight years of Obama. People very conveniently lose sight of that. I doubt anybody could be elected into that office who is going to be smarter than Obama. They would have killed him first before letting him do anything that was going to cause any fundamental changes. So is Oprah going to be better than Obama? In what world? She’s a billionaire. In what world is she going to be better than Obama and not because Obama is so great. At the very least, that wouldn’t seem to be a viable way of thinking. The question is not who’s on the Grammys, not who’s in the president’s chair. It becomes a question of what we are doing. Not the extraordinary exceptions to us.

This kind of cultural production that your focuses on is also a product of lack of canons, or as you have said before, about creating with an absence of materials. Would you call it a pastiche?

It’s a pastiche. But at the same time, when you use the word ‘pastiche,’ it has a slightly negative connotation, as if it is less authentic. Black being is completely bound up in untenable circumstances. Black people figured out how to make culture in free-fall. We are a nation, but we have no land. There is no Constitution of Black Culture. How do you make culture and community in the absence of all of these things that would simply be a given necessity to create community? It’s one of the more fascinating questions of the 20th century and 21st century. Where is the black community going, that big and abstract notion in and of itself?

Consider this migrant crisis. That was our whole history for the past couple hundred years. We know what it means to try to make culture and continuity and build family in the absence of a landmass where you can lay your head, and in the absence of border security. We have already experienced the worst manifestations of several hundred years of callous slavery, in which people could take the person you love, and you never see them or know what happened to them, and the psychoanalytic implications of that. It’s a completely different kind of anger and hurt in a way that sits in your soul differently.

Black people have had to experience this over and over again for centuries. That’s why we are the way we are. It’s super specific. We are at the cutting edge of the most egregious kind of abuse of human beings collectively. It’s not the same context, but some of these similar things are being played out on other bodies now.

Ming Smith’s Mother and Child (circa 1977). Courtesy of the artist and Steven Kasher Gallery, New York City.

Can you expand on the contemporary relevance of blackness, as a canon of philosophy?

I think, in some ways, it behooves everybody to study blackness. Someone like Fred Moten has been super articulate about it: Black people have a privileged relationship to blackness, but its not a proprietary relationship to blackness. Blackness is not the same thing as black people. It’s a new kind of formulation. We came from Africa, but I don’t think it’s a product of Africa. I think if that was the case, it would have popped up in Africa.

Avant-gardism bears some relationship to blackness. To be improvisatory or to be avant-garde is the difference between life and death. Everybody around you had to be avant-garde just to be alive. To teach yourself to read was breaking the law. Your relationship to law is thrown into question. Law and order is thrown into question on a fundamental basis. That’s a different way of being for human beings, to be fundamentally at odds with social order. That’s a new set of circumstances. Human beings have always experienced tragedy, but the blues is something different from tragedy. Blues exhibits certain characteristics that we would associate with melancholia.

Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York City, Rome.

Could you call it melancholic resistance?

We’re resisting and we’re melancholic. So in that sense it is. There is something to be said for the fact that if you have no resistance, you have no life. Humans are born into the world, looking for the most life. They’re looking for love. They’re looking for joy. But the whole idea for black people is, at its core, if you don’t resist, you die. On some level structurally, and inside of a white supremacist environment, black people are associated with death. When I see Jean-Michel’s work, it’s saturated with death. That’s one of the reasons why the work is powerful. I’m trying to understand the basis of his work’s power, how to understand the basis of black musical expressivity as a way to think about how to make a powerful artifact.

How do I make a thing that not only reminds me of blackness or seems to be a manifestation of blackness, but how do I make a thing beautiful and powerful and alienated as well? How do you make a thing that triggers a complicated discourse with artifacts? To get at the meaning of not just being a black person, but also a human being. Because black people are human beings too. I have to remind people sometimes. We are human beings. And to another human being who may not be black, how do you create a thing that embodies blackness in a way that will catalytically force you into some deep, hopefully nuanced and productive consideration of what it means to be black, and to, particularly, be human.

Arthur Jafa’s LeRage (2017). Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise.

Arthur Jafa’s Ex Slave Gordon (2017). Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise.