Law & Politics

Artist Hank Willis Thomas Pulls Work From a South African Art Fair After a Photographer Levels Plagiarism Charges

The artist says he hopes to have a debate with the photographer who cried foul.

The artist says he hopes to have a debate with the photographer who cried foul.

by

Eileen Kinsella

How much does an artist need to change an image to create an entirely new work of art? And what, if anything, does he owe to the original creator?

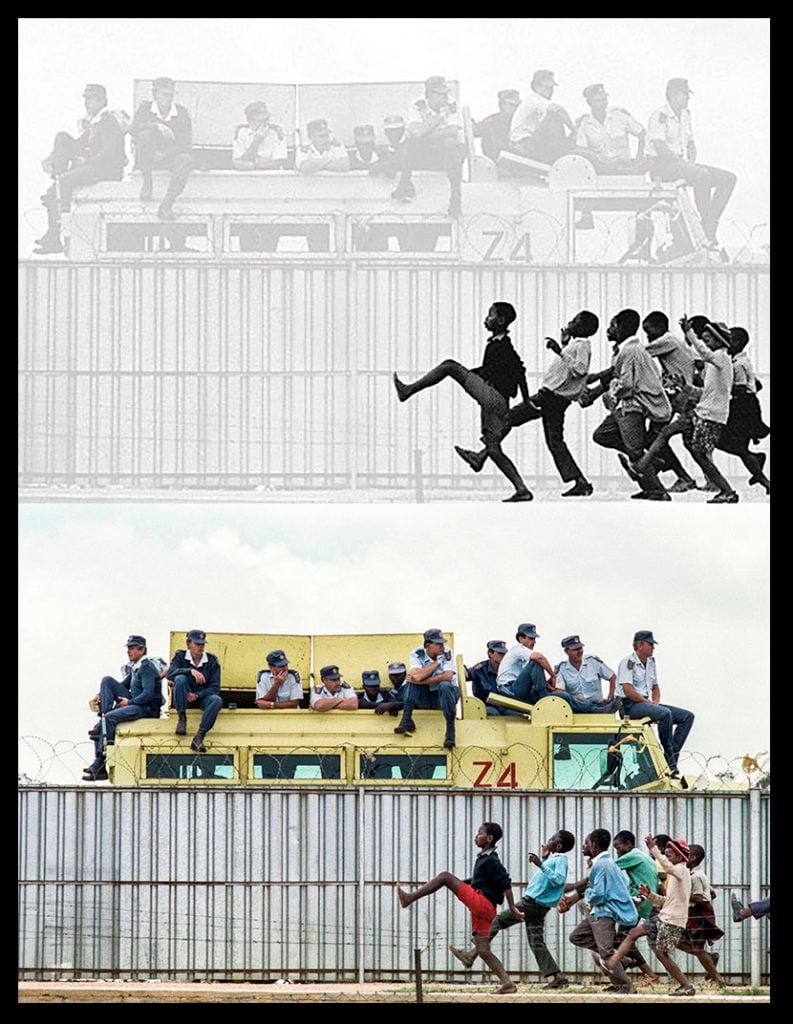

These questions, which have dogged the art world for decades, are at the heart of a new dispute between American artist Hank Willis Thomas and South African photographer Graeme Williams. The photographer was shocked to see a whited-out version of his 1990 image of schoolchildren and police officers, which came to symbolize the end of apartheid, on the wall of Goodman Gallery at the Johannesburg art fair last week.

The day after the fair’s opening, the gallery removed the work from view. Willis Thomas also offered never to show the work again publicly in the future and to loan it to the photographer for up to one year, an olive branch Williams deemed “bizarre.”

Indeed, so far, the photographer is not satisfied with the response. He says he was “astonished” to see the image at the fair and even more “astounded” at the asking price of $36,000, which he says is 25 times the amount of money he has ever earned from the photograph.

Willis Thomas’s changes, he contends, were “minimal”: “It’s theft, plagiarism, appropriation,” he told the Guardian. Williams also claims the gallery was slow to respond to his complaints and that the artist only reached out to him personally after a Facebook post he made about the incident began to attract hundreds of likes.

A representative for Goodman Gallery said the decision to take down the work was the artist’s alone. “He removed the work out of respect for Williams with the intention of entering into a dialogue with the photographer outside of the context of the art fair,” the spokesperson said. Williams insists that there has been “no formal apology or commitment to destroying” the work.

Willis Thomas is known for appropriating images from advertising campaigns and stripping them of context in order to question what the public is truly being sold. More recently, he has begun to remix images of civil rights protests around the world, creating black-and-white compositions that are fully revealed only when the viewer shines a light on the work.

“I can see why he would be frustrated,” Willis Thomas told artnet News. “He said to me that he didn’t feel like I had altered the image enough. The question of ‘enough’ is a critical question. This is an image that was taken almost 30 years ago that has been distributed and printed hundreds of thousands of times all over the world. At what point can someone else begin to wrestle with these images and issues in a different way… much the way that people would quote from a book?”

Willis Thomas says he doesn’t claim to know the answer to these questions, but hopes to have a recorded dialogue with the photographer to explore them further.

The image at issue captures a critical moment in South Africa’s history. It depicts forlorn-looking white policeman seated in a cluster on the roof of an armored vehicle, silently watching a rally in support of Nelson Mandela. On the other side of a corrugated metal wall, a group of smiling black schoolchildren march emphatically forward.

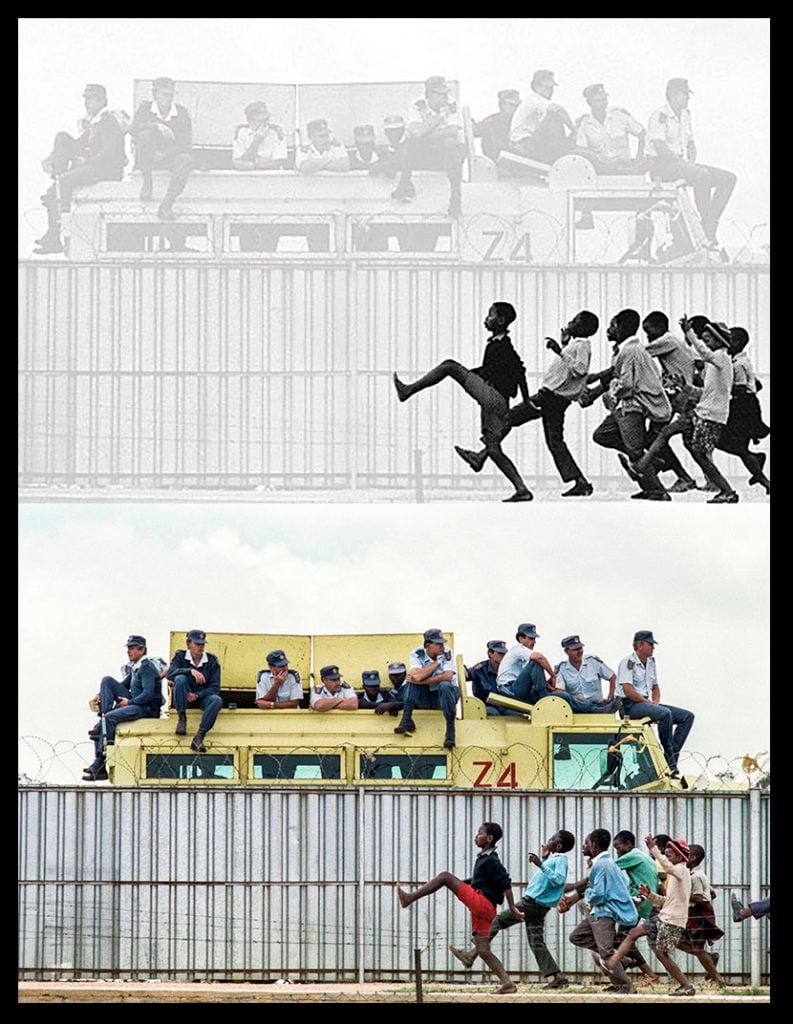

Top: Hank Willis Thomas’s work at the Goodman Gallery booth at Johannesburg Art Fair.

Bottom: the booth following removal of the work. Photo: Courtesy Graeme Williams

The work is now being stored at the gallery. It “has been offered to Williams, who declined the offer,” the spokeswoman said. “Only one edition has been produced of the work. At the moment, there is a conversation between Thomas and Williams regarding what will happen to the work.”

Willis Thomas wants to leave that decision to Williams. “I said, ‘Well you could destroy it, you could sell it, I can send it your other gallery,'” he told artnet News. “It’s not about the commercial side of it…. [It is the] conversation that I actually care about…. Who has the right to represent the historic document of a public event and in what way?”

This is not the first time such a dispute has unfolded. Both Jeff Koons and Richard Prince have been the subject of lawsuits alleging that they did not sufficiently alter another artist or photographer’s image in their own work. “Typically an artist and an original photographer get into this argument and it’s fought out in the courts,” Willis Thomas notes. Disputes over the concept of fair use are often extraordinarily complex because the term is so broad.

Williams says he has received numerous emails from photographers around the world offering support and advice, as well as offers to represent him from copyright lawyers in the US. He is hoping to avoid litigation, but adds, “I have up to now only received an arrogant response.”

Goodman Gallery director Liza Essers says she stands behind Willis Thomas’s work, but is also “very sensitive to Graeme feeling the way he does. One has to respect the fact that photographers like Greame—as a documentary photographer during the apartheid years—were very brave in the work that they did and the images they took in terms of portraying what was happening in the country at the time.”