People

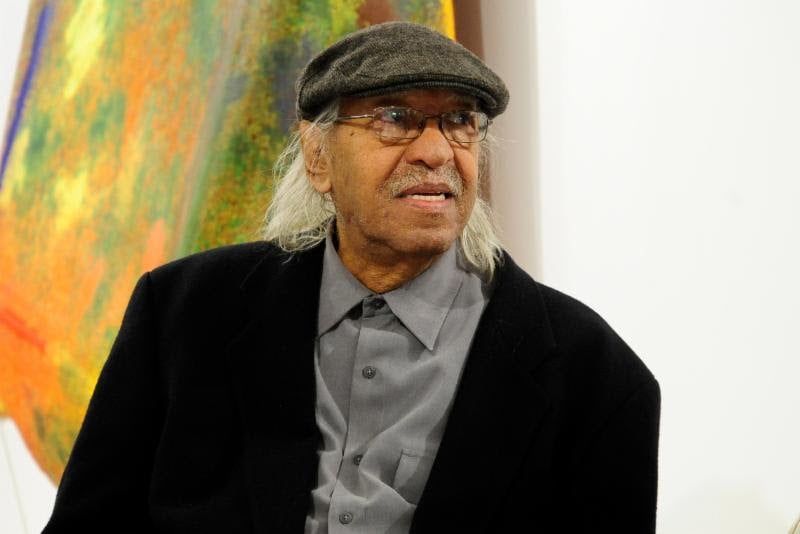

Artist Joe Overstreet, Whose Paintings Jumped Off the Stretcher and Into the Gallery Space, Has Died at 85

Overstreet supported under-recognized artists while tapping into a variety of major postwar American art movements.

Overstreet supported under-recognized artists while tapping into a variety of major postwar American art movements.

Julia Halperin

Joe Overstreet, an American artist who pushed the boundaries of painting by taking the canvas off the stretcher, has died at age 85. During his six decade-long career, Overstreet’s path intersected with many of the most important art movements of the 20th century, from the Beat scene in San Francisco to Abstract Expressionism and the Black Arts Movement in New York.

The artist died on Tuesday night in New York City, his dealer, Eric Firestone Gallery, confirmed. The cause was heart failure.

Although he maintained a healthy distance from any individual movement, Overstreet also worked hard to create space for other artists to build community. An activist and organizer, he teamed up with two other artists to establish Kenkeleba House in the 1970s, a pioneering art center in Manhattan dedicated to showcasing the work of African American and other artists of color who otherwise had few outlets to show in a very white art world.

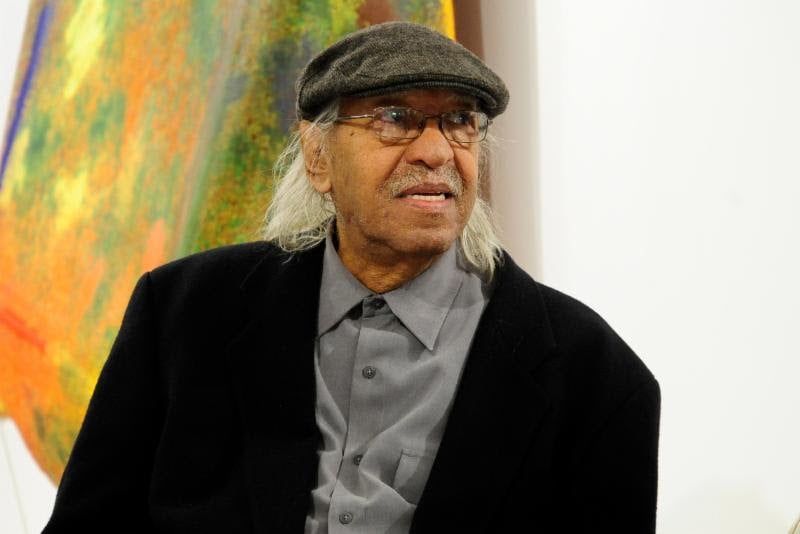

Most recently, Overstreet was included prominently in the landmark traveling exhibition “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” which originated at Tate in London. His work was also included in “Now Dig This!: Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–80” at the Hammer Museum in 2012 and was the subject of a solo exhibition at the New Jersey State Museum in 1996. Last year, Eric Firestone Gallery mounted an exhibition of his “Flight Patterns” series of suspended canvases, made in the early 1970s, which were hung from the ceiling or tied to the floor with a complex systems of ropes and grommets.

“The substance of painting is personal,” Overstreet told the New York Times in 1996, “but experimenting with paint is the fun part. For me, painting the same way year after year would be worse than a prison sentence.”

“Joe Overstreet, Innovation of Flight: Paintings 1967–1972” installation view. Photo courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery.

Overstreet was born in Conehatta, Mississippi, in 1933. His father was a mason, offering him early exposure to architecture. Like many African American people who were part of the Great Migration, he and his family moved several times before eventually settling in Berkeley, California. Overstreet worked as a merchant marine and as an animator for Walt Disney Studios before he began studying art at Contra Costa College and the California School of Fine Arts. During the 1950s, he became a member of the Beat scene in San Francisco and published a journal titled Beatitudes Magazine out of his studio.

In 1958, he moved to New York with his friend, Beat poet Bob Kaufman, and took a job designing displays for store windows. A regular at the Cedar Tavern, he immersed himself in the work of Abstract Expressionists including Jackson Pollock, Hans Hofmann, and Willem de Kooning. The latter artist took a particular liking to Overstreet and is said to have once given him a few works to sell to help him make ends meet.

While some African American artists who worked in abstraction in the 1960s were considered at odds with the Black Arts Movement, which sought to fuse activism and art and to celebrate the black experience with uplifting imagery, Overstreet had a foot in both realms. During the late ’60s, he participated actively in the Civil Rights Movement and worked as art director of the Black Arts Repository Theatre/School in Harlem. In 1964, he created one of his best-known works, The New Jemima, which depicted the pancake mix mascot with a machine gun instead of kitchen equipment.

Also during this time, Overstreet developed his best-known abstract series, “Flight Patterns,” which took the canvas off the stretcher and into the gallery space. The folded compositions resembled origami objects suspended in midair. Of these works, he said, “My paintings don’t let the onlooker glance over them, but rather take them deeply into them and let them out—many times by different routes. These trips are taken sometimes subtly and sometimes suddenly.”

In the 1970s, Overstreet teamed up with artist Corrine Jennings and writer Samuel C. Floyd to establish Kenkeleba House, a space dedicated to supporting art, performance, and literature by African American artists at a time when almost no one else would show them. The space, which exhibited artworks by artists including David Hammons and Norman Lewis, still exists today.

“Joe Overstreet was a pioneer of experimental techniques and processes in painting,” Jennifer Samet, director of research at Eric Firestone Gallery, told artnet News in a statement. “His work explored the realities of African American history, embedding content within abstraction. He was a significant community organizer who influenced generations of artists.”