This is part one of a two-part series on the rise and fall of the Artist Pension Trust, founded on the premise that artists could join together to create a shared nest egg in a precarious profession. What could go wrong? Read on to find out, then continue to part two here.

A year ago, deep into the pandemic, nearly 150 artists began strategizing. They were among those who had joined the Artist Pension Trust (APT) in the years since its 2004 inception, and they were worried.

Over the past two decades, APT collected more than 13,000 artworks with a combined value estimated at $500 million from its 2,000 members—artists who had signed on hoping to invest in their own futures as a kind of insurance policy against the market’s inevitable ups and downs. But by 2017, nearly all communication from the fund’s founders had ceased. Instead, the artists found themselves confronting a kind of zombie corporation, unable to obtain basic information like where their works were stored, or even receive responses to their emails.

The New York Times picked up the story, and in July it published an investigation that detailed where APT claimed to be storing their work: warehouses in Liverpool, New York, and Leipzig, Germany. A day after the Times story ran, painter Jane Fine received a phone call from a lawyer, Laurence Eisenstein. Eisenstein, a collector who owned a large painting of Fine’s and whose law firm has helped recover Nazi-looted art, wanted to help APT artists get answers.

Eisenstein wasn’t quite sure how much he could do, but agreed to helping a group, which would not require much more effort than helping one artist. Fine assembled 15 APT members, the majority based in New York (she included two artists, Dawn Clements and Kanishka Raja, who are deceased, because she was particularly concerned about the future and status of their artworks).

With Eisenstein’s help, the group specified their demands. They wanted their work back; they wanted APT to pay for shipping; and they wanted their work removed from MutualArt.com, an art analytics website that is also APT’s parent company. They wanted out of contracts they believed APT had violated.

Jane Fine, Bad Signs (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

Then they were faced with another problem: to whom should they serve papers?

“The main issue is, what is APT at all?” Fine told Artnet News recently. These days, only one part-time staffer responds to emails, private sales advisor Ashley Dillman, who also works as a real estate agent. MutualArt is registered as a British Virgin Islands company, and thus difficult to sue. And Moti Shniberg, the entrepreneur who co-founded APT and MutualArt, says there is no longer any active management at the company. “It’s such a mystery,” Fine said. “What are they trying to do?”

“I doubt they are going to give us our work back,” she added.

Shniberg, who responded to Artnet News’s questions via email, confirmed Fine’s fear, claiming that returning some artists’ work “would lead us to reneging on our contractual obligations to all of these artists.” Instead, Shniberg said, he is “exploring options to pass APT on to a credible institution” and stressed that he is doing so with no desire to profit.

But while APT may now appear only to exist as two unmanaged troves of artwork in long-term storage, the fund is also proprietary intelligence—and has been from the start.

***

APT began taking shape in early 2004. Shniberg has said the idea came from talking with an artist friend in the back of a New York City taxi and realizing that artists by and large have no pension plan. What if they were to invest in a fund based on the prospective future value of their own work?

This idea formed at a moment before the Great Recession, when optimism about the art market was running high. New data suggested art could be a leverageable asset: in 2002, finance scholars Jianping Mei and Michael Moses published “Art as an Investment and the Underperformance of Masterpieces,” a paper in which they debuted a new index for measuring art sales and proposed that art could be a “more glamorous investment” than fixed-income securities—in other words, not only was art sexier than a treasury bond or money market investment, it could also be more profitable. When Shniberg first patented APT’s risk management model, he cited the Mei-Moses study.

Moti Shniberg. Photo: © 2014 Patrick McMullan Company, Inc.

For artists, however, the appeal was more utopian: a model that allowed them to help themselves while looking out for others. As curator Carole Ann Klonarides put it to Artforum in 2004, “Let’s say an artist is extremely successful. Then they’ll be able to say, ‘I’ve also helped out my community of artists.’”

As APT took shape, Shniberg partnered with Israeli risk management expert Dan Galai, his former professor at Hebrew University (“I decided I had nothing to learn, so I dropped out,” Shniberg told Wired in 2005). Galai had studied under Milton Friedman, Ronald Reagan’s unofficial economic adviser, and co-created an index to track stock volatility in the 1980s.

The initial plan they devised was this: for 20 years, artists in the trust designate one work for APT annually; when the fund sold an artist’s work, 40 percent would go to that artist, 32 percent would be split among the collective, and 28 percent covered APT’s administrative fees. This way, even if the market for one artist’s work wanes—as happens to most at some point over their careers—they’ll have some money coming in. A big enough pool of artists would diversify the risk. APT promised to handle storage and give artists regular condition reports.

Shniberg and Galai then reached out to David Ross, the former director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Ross said that the “shorthand” Shniberg and Galai used compelled him: they talked about setting up a structure “that will allow the best aspects of market capitalism and a kind of socialism to be combined to support artists in ways that they weren’t being currently supported. And quite frankly,” he added, “still aren’t being supported.”

Ross signed on as co-founder and president. APT launched in 2004 and 2005 with chapters in New York and Los Angeles. Once a chapter reached 250 artists, it would close. Over the next five years, APT began chapters in London, Mexico City, Berlin, Beijing, Mumbai, and Dubai.

Early on, the press focused more on how APT would buck the “starving artist” stereotype than its founders’ backgrounds. Artist and writer Gregory Sholette was among the first to question the model in print, noting Galai’s indirect ties to Reaganomics in a 2008 Artforum essay. At the time, Sholette saw APT as further evidence of artists’ turn from collectivity toward private market mechanisms.

“What interested me about APT was how it plugged into the neoliberal plot,” he told Artnet News. “Everyone is their own little bundle of collateralized risk.”

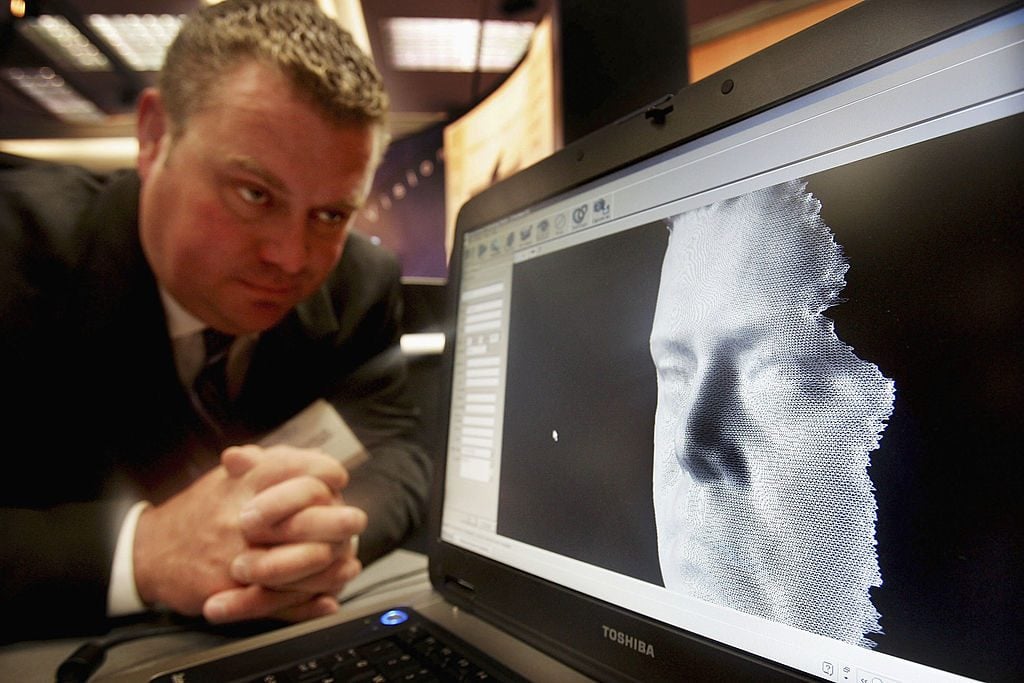

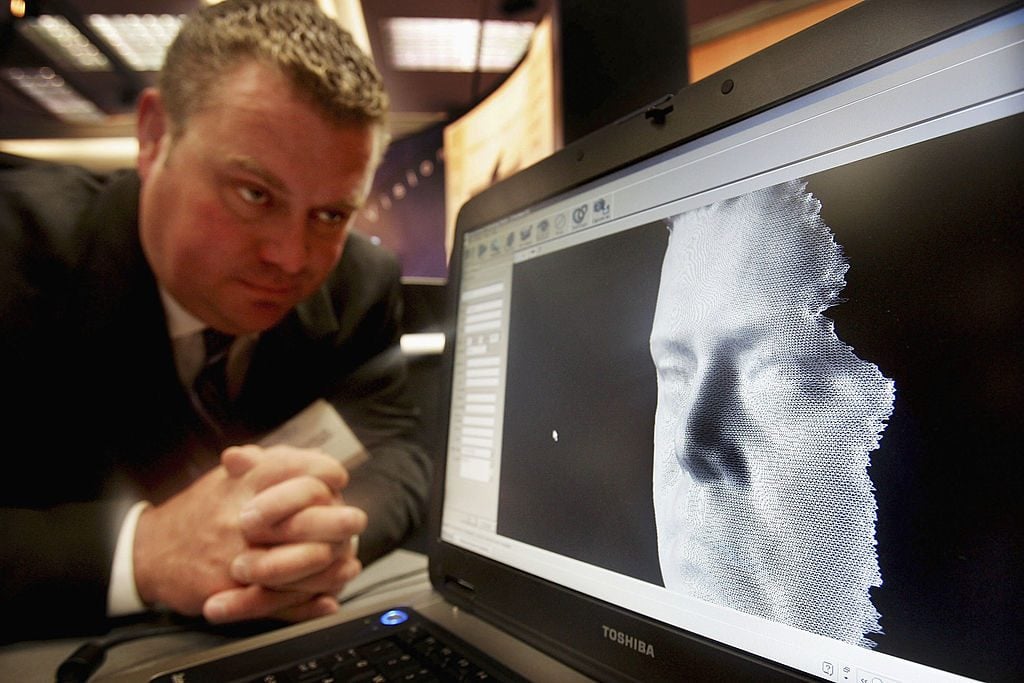

A 3D facial recognition program demonstrated during the Biometrics 2004 exhibition and conference October 14, 2004 in London. (Photo by Ian Waldie/Getty Images)

After all, APT was the brainchild of a serial entrepreneur who was in the business of devising patentable new financial and technological models. Shniberg first made money in the late 1990s with an Israeli company called Image ID, which developed a program for recognizing patterns within images. Since then, he has started a profusion of projects involving facial recognition, relationship mapping, image identification, phenotype tracking, and data collection.

These include Vizi Labs, which later became the facial recognition site Face.com; FDNA, which uses artificial intelligence to detect disease-causing genetic variations; CyberMDX, which provides cybersecurity for medical devices; and Seed-X, which uses A.I. to analyze genetic traits in seeds, touting itself as a “game-changer for the entire farm-to-fork industry.” In 2017, he co-founded Plowshare Ventures, a venture capital fund focused on defense and commerce, with two former military officers, one of whom is now Israel’s deputy prime minister. (Plowshares has since dissolved.)

One common denominator across Shniberg’s ventures is a reproducible, and thus patentable, model or algorithm. He has applied for at least 38 applications across the U.S., Australia, India, China, the Republic of Korea, Canada, and the European Patent Office since 2001. In 2012, he and his Face.com partners sold the patent for their facial recognition and relationship-mapping program to Facebook for an estimated $60 million.

He filed his most notorious trademark application on September 11, 2001, at 5:37 p.m. Eastern time. The towers had just fallen, and he decided he wanted to trademark “SEPTEMBER 11, 2001” to advertise “entertainment in the nature of visual and audio performances, and musical variety, news and comedy shows,” according to the application. The USPTO denied the application, calling it “misdescriptive,” as the public would assume the trademark referred to the terrorist attacks.

Shniberg told Artnet News that his only motivation was to ensure any commercial value “would go back and benefit the people that [were] actually hurt.” He added that Artnet News’s previous coverage of the trademark application was suspect, since its parent company, Artnet, also runs an auction database. Shniberg further noted that his work with APT and MutualArt “does not relate to my other activities in any way,” as he has no ambitions to profit from APT, and only “cares about the company and the mission.”

***

Ironically, it was an artwork by an artist APT was recruiting that prompted greater scrutiny of the venture.

In 2010, artist Walid Raad made APT and its founder the subject of a lightly fictionalized, performative lecture, which prompted some of his peers to begin questioning Shniberg’s motivations. Raad, who is from Lebanon and based in the UAE, was invited to join the Dubai chapter of APT in 2007. He was intrigued for the same reason others had been.

But once Raad started looking into Shniberg, he learned that Image ID, Shniberg’s first company, had close ties to Israeli intelligence. As an artist who left Lebanon just after the Israeli invasion, he found this information disturbing—and at first, he just wanted APT to be transparent about its Israeli intelligence ties when recruiting Arab artists, who could in fact be endangered by this association.

Walid Raad in “Question the Wall Itself” at the Walker Art Center. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

Eventually, he says, he met with Shniberg himself, whom Raad described as “the most beautiful man I have ever seen.” Shniberg, he said, scoffed at his concerns. “In Israel,” Raad recounted Shniberg telling him in the 2010 performance, “the tech sector is often linked to military intelligence. Please don’t tell me that you are one of those naive left-wing, head-in-the-sand pontificators who actually think that the cultural, technological, financial, and military sectors are not, and have not always been, intimately linked?”

While most of the details Raad related on stage—about the financial model and the IDF ties of APT’s founders—check out, he has called the performance a fiction. Even if his quotes were not verbatim, the gist was clear: the world of international venture capital had little interest in an artist’s ideals.

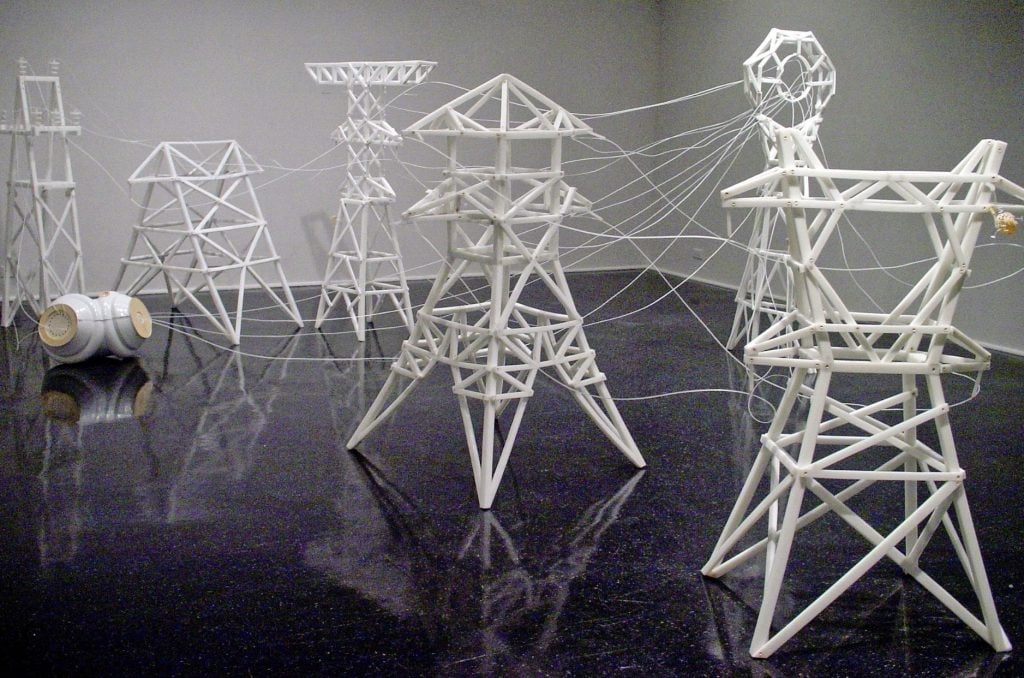

When Raad performed this lecture at RedCat in downtown Los Angeles, APT artist Shirley Tse was in the audience. “Everything he showed was not surprising, in a way,” Tse recalled. “But I’m like—pardon my French—fuck. And I was seriously thinking about pulling out, from an ethical standpoint.”

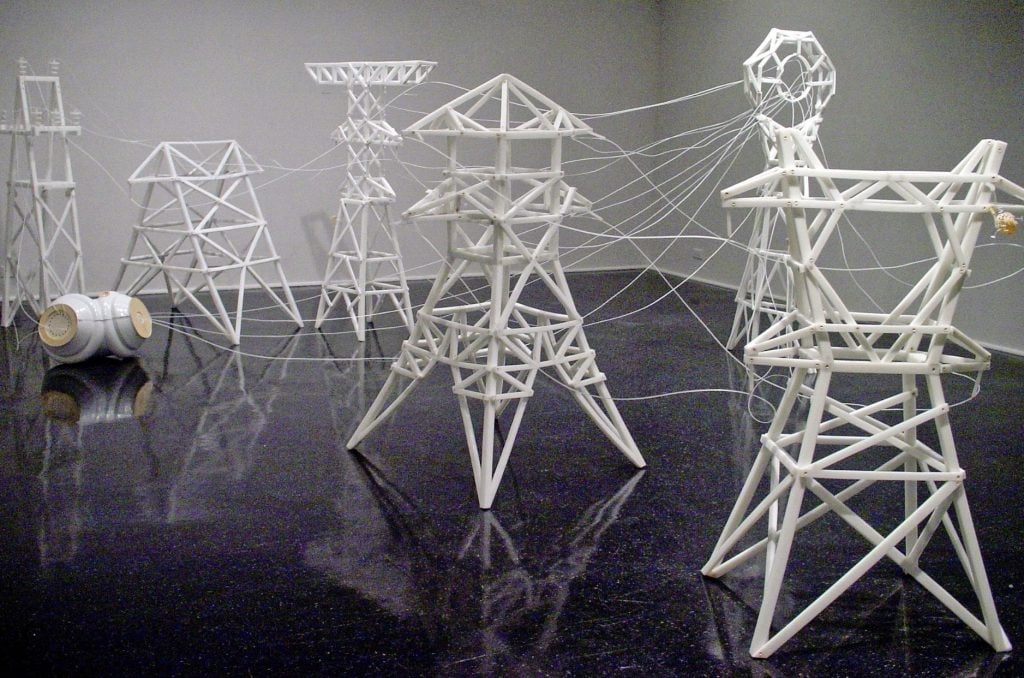

Tse had entrusted APT with her installation-sized sculpture Power Towers and couldn’t afford to transport and find new storage for the work. Around the same time, with the establishment of MutualArt.com, Tse started to notice the interest of APT’s founders shifting toward data collection.

“I think they realized—as they’re gathering this pool, as they’re expanding globally, beyond L.A. and New York—that they can map this inventory of artists and their work and their value, and how they develop, and we would all tell them when we have shows, and keep them abreast of our development,” she said. “At some point, I guess they switched the focus from physical assets to information assets.”

Shirley Tse, Power Towers, (2004). Installation View at the Pomona College Museum of Art. Image courtesy of the artist.

In fact, early patents suggest that information assets were a primary focus from the start. During the first two years of APT’s existence, Shniberg filed multiple applications to patent APT’s investment model.

The first, filed on January 7, 2004, before the trust had begun formally accepting artists, patented the “business model for the diversification of risk in connection with works of art [which] includes accepting from various artists works of art to be pooled in a collective investment fund.”

The “summary” section of this patent application describes how databases will be used to “store information about the artists, the works of art that are pooled in the collective investment fund, financial instruments issued to each of the artists in consideration for the works of art contributed by the artists to the fund, and revenues obtained on behalf of the fund through commercialization of the works of art in the fund.” In other words, a key component of the plan for APT had been to record data about the artists and their work’s trajectories and markets. The patent application also adds that such an effective database should cut down on the need for personnel, suggesting an efficient automated system fueled by information.

By 2007, Shniberg had launched MutualArt.com, an art-world analytics website with software designed by Israeli data scientist Ronen Feldman, who famously coined the term “text mining” but had no previous art experience. Yet the relationship between MutualArt and APT—and which aims they served—has always been muddled.

MutualArt INC was the name under which APT was founded—trust-related patents were assigned to MutualArt INC as early as 2004, and Shniberg said they used the name for the market website partly because he had already trademarked it. But in early interviews promoting the website, Shniberg rarely mentioned APT. He maintains that MutualArt “was always intended to serve the whole art market, and not just APT.”

Then, in 2016, MutualArt.com and APT merged. The press release claimed that the union would “expose the APT collection…to MutualArt.com’s key audience.” Images of APT works were uploaded to the site, as well as recent auction data for APT artists, though many did not sell regularly at auction, if at all.

At the time of the merger, it wasn’t clear to outside observers what it all meant: art-market commentator Marion Maneker wrote that it was “not readily apparent” how APT and MutualArt could help each other, nor, he added, “is there an obvious business model for either company as a separate entity or combined.”

A work by York Chang, New Mumbai, from the series “All Dogma Has Its Day” (2010) in the APT collection. Image courtesy of the artist.

Although APT artists told Artnet News that they do not feel that the MutualArt.com site serves them well, potentially even undermining their works with its inconsistent jpeg quality, missing images, and clunky navigation, Ross, who sat on MutualArt’s board of directors early on, saw some potential—especially if the goal really was exposure.

He thought that one way of generating revenue for APT was to harness the trust’s “remarkable network” of curators and artists. Their vast knowledge could be shared with MutualArt’s paying subscribers, and then the resulting funds could be used to support APT artists. Instead, in a move Ross considered a misstep, soon after the merger, MutualArt leadership opted for another way of generating income: selling APT art at auction. (See part two of this story for more on the fate of the auction strategy.)

Meanwhile, Shniberg continues to spin. He told Artnet News that “possibly focusing on digital works, using NFTs,” could improve the APT model in the future, further cutting down logistical costs. Yet the artists have more pressing concerns, namely their physical artworks—whose integrity may be at risk or value decreasing in storage.

In addition to the 15 artists pooled by Fine and Eisenstein in New York, artist Shaun Leonardo has hired lawyer Robert Cosgrove, and a group of artists from the Los Angeles APT pool have begun working with lawyer Paul Cossu. So far, 61 Los Angeles artists have signed retainer agreements, in addition to the five artists serving on the group’s legal advocacy committee. “We are collectively seeking to obtain a condition report on our work,” explained L.A. artist York Chang, “and to retrieve our work from APT.”

The next step is to serve a demand letter to the company—and then hope their art will come back to them safely, sometime soon.

Continue to part two here.