Art World

A New Generation of Idealists Is Learning From the Artist Pension Trust’s Mistakes. Can They Deliver on Its Promise?

In the final installment of our two-part series, we examine the legacy of APT.

In the final installment of our two-part series, we examine the legacy of APT.

Catherine Wagley

This is part two of a two-part series on the rise and fall of the Artist Pension Trust, founded on the premise that artists could join together to create a shared nest egg in a precarious profession. What could go wrong? Read part one here.

The promise of financial security first drew many people to the Artist Pension Trust. But they were also attracted to the program’s collective character, in which the success of the few could benefit the many.

It was an inspiring idea: artists contribute work to a pool that would, in the next 20 years, be sold off for the good of the group. In addition to the safety net it offered over the course of an inevitably fluctuating career, artist Shirley Tse, who joined the trust in 2005, said she was compelled by “a kind of collaborative existence that is not competitive—not one against another, but cooperative.”

In a wry twist, perhaps the truest expression of APT’s collaborative spirit has been found in artists organizing to get their work back from the very organization that peddled that utopian vision in the first place. Recently, for example, the legal advocacy committee for APT’s Los Angeles chapter, a group of five artists liaising with lawyer Paul Cossu, sent out a survey to the chapter’s full membership to ensure their demand letter would take into account the needs of all.

While the artists joining forces and lawyering up want first and foremost to determine if their work is safe, there are also bigger, broader questions on their minds. Why had something so promising faltered? Could a venture like this—a trust, or a comparable effort toward sustainability in this precarious profession—actually work? Or is the schism between the market’s whims and artists’ needs just too great?

They are not the only ones asking. Other collectives have watched the struggles of APT artists carefully as they try to realize their own cooperative visions in different, often smaller ways.

York Chang, Requiem from the series “All Dogma Has Its Day”, (2010). Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist.

Some artists doubt APT could have ever worked as envisioned. As L.A. artist York Chang put it, “The fundamental problem with the model is that APT simply doesn’t understand how artwork accrues value.” He continued, “The value of artwork doesn’t just accrue over time like real estate in REITs, nor does artwork have built-in income-streams like mortgage-backed securities.” Rather, he said, the value of art grows in proportion to how well the work is nurtured, exhibited, written about. And APT wasn’t set up to provide that kind of 360-degree care.

***

Early on, when APT began recruiting artists, they relied largely on trusted local curators to make the initial sales pitch. In L.A., Irene Tsatsos, Carole Ann Klonarides, and Pilar Tompkins Rivas were among APT’s advisors. According to a document APT filed with the U.S. SEC in 2005, the plan was to enlist members of the advisory boards and selection committees as independent contractors.

Tse recalls some initial skepticism among artists; even she was confused about whether the organization was legitimate. But a presentation by co-founder David Ross, a former director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, convinced her. “All these people who invited me to join were legit and trustworthy,” she said.

At first, this network of local representatives insulated artists somewhat from APT’s business side. But as APT entered its second decade, infrastructure for supporting the work further dwindled and alleged mismanagement—or, at the very least, lack of management—became more apparent.

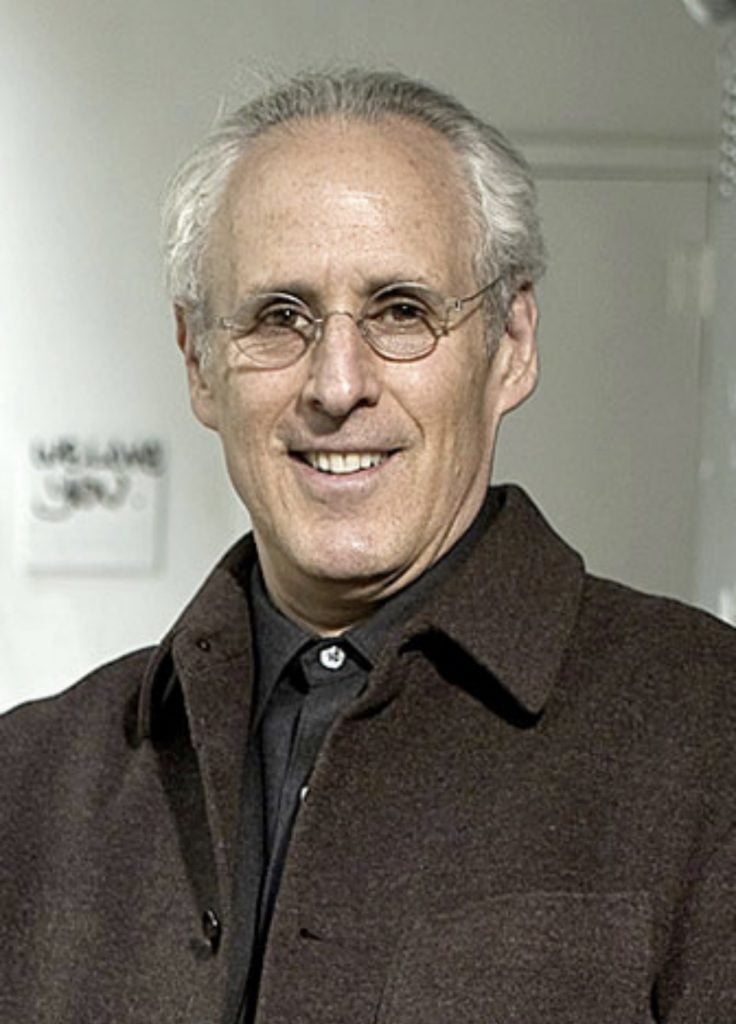

David Ross, a co-founder of APT and the former director of the San Francisco Museum of Art.

Ross, who believes the “people who still respect what APT did probably outnumber those who are complaining about it,” does not think the model itself has fallen short. Rather, he said, it simply remains unproven, as the initial plan had been to allow the artwork to accrue value over 20 years.

“APT hasn’t failed,” he said. “It has failed some artists, because it’s making life difficult for them.” But the “failures are not the failure of imagination; it’s the failure of people to make the appropriate refinements at the appropriate time to keep this moving.”

In 2007, Ross tried to make necessary refinements by founding the APT Institute. “It was kind of my last-ditch effort to say, look, if we’re going to try to really do the most we can for all these works,” he said, “let’s try to set up the equivalent of a non-profit.” The idea was to secure donor funding for exhibitions and publications to boost the profile of APT artists—in other words, to provide some of the services a good gallery does.

The institute did not succeed—Ross cited the 2008 crash as one factor—but “had we been able to make that work,” he maintained, “I think it would have added fuel to the fire.”

Elana Mann, Can’t Afford the Freeway (2007–10), part of the APT collection. HD video still. Image courtesy of the artist.

***

The recession punctured the optimism that had inflated the art market in the early aughts. The plan had initially been to wait for the art in the APT collection to appreciate and to explore other options for revenue generation in the meantime to support operations. But in 2010, APT’s then-CEO, curator and advisor Pamela Auchincloss, told the Financial Times that she was beginning to evaluate some APT works for possible sale. She was also entertaining other possibilities, like setting up a diversified art mutual fund.

In 2012, Auchincloss, who prefers not to comment on APT publicly, left. No one replaced her. APT stopped loaning art to institutions because doing so was too expensive. Storage costs and staff turnover put the trust under increasing strain.

In 2016, after MutualArt and APT merged, APT announced it would sell art from its collection at auction. APT’s first sale at Sotheby’s New York in March 2017 earned a middling $230,000.

Sarah Murkett, who joined MutualArt and then APT as director of sales in 2013, voiced opposition to the auctions and believes she lost her job as a result. “I did not think that there was enough of a market for the works to be able to maximize their value by selling them at auction,” she told Artnet News recently. “I thought the works would sell below their retail value.”

She wasn’t the only one concerned. In April 2017, APT aborted a second Sotheby’s auction of work from the trust after artists and their galleries argued the sale might endanger their markets.

Screenshot of Sotheby’s sale: First-Ever Auction of Artworks from Artist Pension Trust, 2017.

That summer, MutualArt’s CEO Ayal Brenner, who had become a public face of the trust, made an announcement that arguably frustrated artists even more than the planned sale. Moving forward, he said, APT members would have to pay a $6.50 monthly fee to keep their work in storage. If they did not pay, they would have to arrange to transport the work and store it elsewhere at their own expense.

After a group based in the U.S. enlisted lawyer Gregory Clarick to protest, noting that artists’ original contracts ensured APT would cover “safe and secure” storage, the company eventually backed down.

Soon after that, however, artists say communication from the company all but ceased. They stopped receiving the annual reports on their work that they were promised in their contracts (APT co-founder Moti Shniberg told the New York Times these reports were too expensive to produce). Many never heard from their previous APT contacts again.

Murkett, who now leads an art-world recruiting firm, called APT’s initial goals “fantastic, even noble.” But the reality did not match the promise. “By making the artworks in the collection unavailable to the artist members who created them,” she said, “they have violated any sense of trust and are now actively causing harm to this vulnerable group.”

***

Could the APT model work under different circumstances? Given how expensive it is to properly care for a collection, let alone lend art to exhibitions and properly promote it, Murkett is not sure.

“The idea of APT is as a commercial enterprise, assuming enough value creation to support hundreds, if not a couple thousand artists in retirement, as well as the operational expenses,” she observed. If the value accrues over a multi-decade period, then the model would rely on investors paying carrying costs in the meantime. “It’s certainly not impossible,” she concluded, “but it is a risky business model.”

APT co-founder Moti Shniberg (second from right) alongside Glenn O’Brien, Jeffrey Deitch, Judith Benhamou-Huet, Simone DePury, and Neville Wakefield among others in 2007. Photo by Neil Rasmus/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images.

APT’s success depended on its scale—risk had to be carefully diversified across regions, mediums, and markets; the collection had to be large enough, and still exclusive enough, to convince investors that the plan would pan out. Yet with eight international chapters and 2,000 artists, it was difficult to deliver the care each one needed to thrive.

“If there is any operation that can function on behalf of the long-term financial interest of artists, it must be scaled down and capitalized in a sustainable way,” said artist York Chang.

***

Some organizations have sought to realize their own versions of what APT promised. Curator, artist, and consultant Corrina Peipon and artist Debra Scacco founded the still-evolving Contemporary Art League during the first year of the pandemic. They watched APT’s implosion with interest and spoke with participating artists about their experiences.

“The APT example kind of shows that when you isolate artists from all the other sectors of the contemporary art economy, this very quickly becomes pretty problematic,” Peipon said. She and Scacco are not envisioning a fund, but rather a kind of commons where art workers across the field—curators, advisors, artists, preparators, administrators—share resources and knowledge. They hope this resource bank could achieve some of the goals that initially drew artists to APT: a desire for a safety net, and to feel they weren’t in it alone.

Peipon and Scacco spent a year asking California arts professionals what they needed, and found that healthcare, childcare, and access to capital were among the top contenders. “We’re trying to be a support network for very basic quality of life services that just enable people to function well,” Peipon said, explaining that dues will support the member-owned organization, but that these will be on a sliding scale.

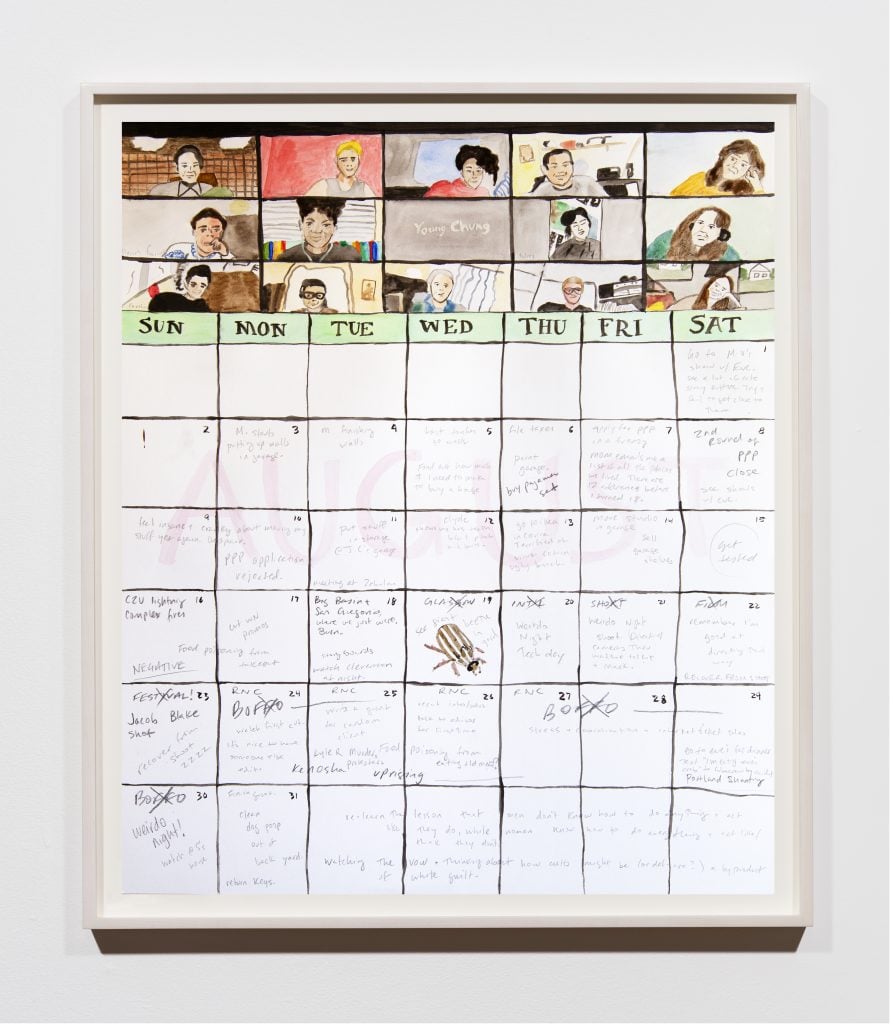

Commonwealth & Council, Family Zoom. Courtesy of Commonwealth & Council.

While the Contemporary Art League takes a more holistic, open approach to collective support, Young Chung and Kibum Kim, who run the Los Angeles gallery Commonwealth and Council, are trying out novel approaches for getting funds directly to artists. The idea came out of the monthly virtual check-in meetings the gallery held for its 30 artists during the pandemic. “We were all talking about our mutual wellbeing and our future together,” Chung said.

They decided to ask collectors to forgo standard discounts and, instead, offer that money to what they’ve christened the Commonwealth Fund. In 2021, they managed to raise $100,000. Though Chung and Kim initially imagined that they would put that money toward artists’ healthcare, they planned a community meeting to finalize how it will be used. They want decisions to be made by the group.

While all artists on the roster participate in the Commonwealth Fund, a second initiative, the Council Trust, works differently (and a bit more like APT). Gallery artists can opt in with a work valued between $15,000 and $20,000, ensuring that everyone enters at a comparable price point. When a work is sold, the profits are split equally between each artist in the trust (unlike with APT, where the individual artist whose work sold got a bigger cut).

“It is about the redistribution of wealth,” Chung said. “It’s about having faith in one another and having to look out for one another.”

Commonwealth & Council, August 2020. Courtesy of Commonwealth & Council.

Against the backdrop of these new, scaled-down initiatives, APT artists are left wondering how to protect and envision a new future for their own work, still out of reach in the company’s storage facilities. If they are able to get it back, where should it live? Are there local institutions that might want to take on each chapter’s work as a discrete collection?

Shniberg, APT’s co-founder, told Artnet News he is “exploring options to pass APT on to a credible institution that understands the importance of this mission and the value of the sharing/risk diversification model,” though it is not yet clear what kind of institution that might be.

L.A. artist Ashley Hunt said he no longer expects any kind of pension or payout. But part of the appeal of APT was that it was a collection that would be stewarded. “Is there someplace where this trove of work that now has kind of a shared identity, at least through this weird blip on 21st-century art history, could have value to somebody?” he wondered. Could an institution or collecting body see this work as articulating something about an era, or even a artists’ shared desire for security and collectivity in a precarious market?

“Maybe the collection,” Hunt supposed, “could be a monument to the failures of late capitalism.”