Art World

12 Habits of Highly Effective Artists, From Creative Exercise to Living in Airplane Mode

George Condo, Liza Lou, and other artists tell us the everyday rituals that help them create their best work.

George Condo, Liza Lou, and other artists tell us the everyday rituals that help them create their best work.

Rachel Corbett

What makes some artists more successful than others? Talent, luck, and hard work certainly play a part, but there are other, subtler habits that many of the greats seem to have in common. We asked 11 artists about their work routines and the way they structure their lives to see how these everyday rituals, big and small, make them tick. Below, see the 12 habits that help these artists create their best work.

Airplane mode. Courtesy Apple.

Martha Rosler calls it the “third-space effect”—a work environment so controlled that the “world shrinks to a bubble around myself, without the distractions of my daily life or environment or people.” One place she has this feeling is in airports. “I wrote one of my most-cited essays largely at the Atlanta airport way back in 1980 or ’81. I have often found myself able to concentrate in airports, but only if the waiting area isn’t packed, or if I can sit in a place that has tables,” she says.

Of course, flying itself offers even more complete containment. “I have the least distractions on airplanes,” says artist Hank Willis Thomas. Even at home, he says, “Sometimes I mimic this by turning off my phone and internet.”

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Staying focused on work is easy when everyone thinks you’re out of town. “I just put an out of office reply on my email address,” says the painter George Condo. “Usually I just pick random dates for when I supposedly will be back.” Indeed, as of this August, Condo’s auto responder says he is “out of the studio until the 4th of July.”

National Public Radio headquarters. Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images.

Why is NPR playing around the clock in so many studios? “Making a painting has no soundtrack,” says the painter and writer Walter Robinson. “It’s not something you need to construct out of words, like art criticism, say, which is the other thing I’ve spent a lot of time doing.” That’s why so many artists listen to talk radio while they work. Robinson, however, actually prefers audiobooks or Bloomberg to NPR. (“Public radio strikes me as unbearably middlebrow.”)

The sound of the radio can also contribute to Rosler’s sacred “third space.” “I like to have a background noisemaker or soundtrack,” she says. “I regard all this as a controllable curtain of noise insulating me from the surrounding uncontrollable universe.”

Other artists prefer music, though they don’t always seem to care about what kind. The painter Angel Otero says he “always” has it on: “Jazz, salsa, bossa nova, trip-hop, hip-hop—depends on the mood.” Condo, meanwhile, just plays the same John Coltrane Live in Sweden CD every day. “I just go in and click it on, and it plays over and over, then I do the same thing the next day.”

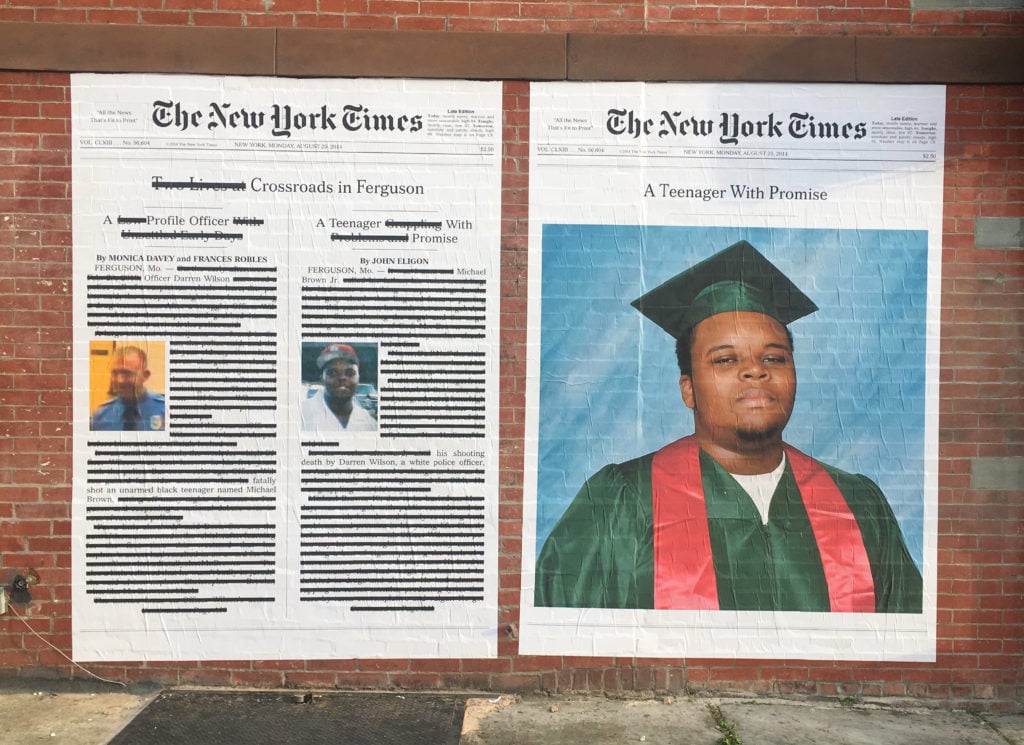

Alexandra Bell, A Teenager With Promise (2017). Image courtesy the artist.

Yes, even when it’s bad—especially when it’s bad—artists can learn from the communication methods employed by the media. “I have found the news inspiring, both because of its power to manipulate our emotions through selective presentation of information and for the seductive fashion in which it is presented,” says Willis Thomas. “I am also inspired by our president and many of our leaders. They remind me why I do what I do and why I need to do and know more.”

Tim Youd retyping Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (July 2017) at Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York.

The habit most commonly shared among artists is a commitment to answering emails first thing in the morning—and then not thinking about them again. “I wake up early and answer emails, but then the rest of the day I try to work more creatively,” says Shirin Neshat.

If one doesn’t learn to separate these two aspects of an artist’s work, says Zoe Buckman, “the administrative side of the art practice can eclipse the making of the art practice.”

“This is my form of procrastination,” says Betty Tompkins. “In the morning, I do emails, walk, social media, and errands.” In the afternoon, she’s ready to paint and draw.

Marinella Senatore, Protest Forms: Memory and Celebration Part II. Performance by Graham 2 from the Martha Graham School. Courtesy of the Queens Museum. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

Exercise has long been associated with improved mental functioning, and there’s no reason it can’t also be approached creatively. “I practice Indian Clubs and Iranian Meels training several times a week,” says the painter Billy Childish (both are cone-like weights, the latter dating back to the Persian Empire), “as well as prayer and yoga.”

“My biggest inspiration comes from studying African dance, which I have been doing for many years,” says Neshat. “It has become my secret ritual.”

Polly Apfelbaum assembling Mojo Jojo at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2013. Image © PAMM.

Art-making is often a solitary activity, requiring enough self-discipline to structure one’s own time. “I work eight hours a day consistently—and if I don’t manage it during the day, I make up for it in the evening,” says Liza Lou. “It’s a lot like being an athlete: you train under all conditions. Just get in the studio no matter what you feel like.”

For those up to the responsibility, this freedom can be wonderfully simplifying—there’s no one to blame if work doesn’t get made, but there’s also no one to answer to. “I have always had a very DIY way of working—no complicated technology, very few studio assistants,” says Polly Apfelbaum. “So I can always pick up and go and carry the work myself.”

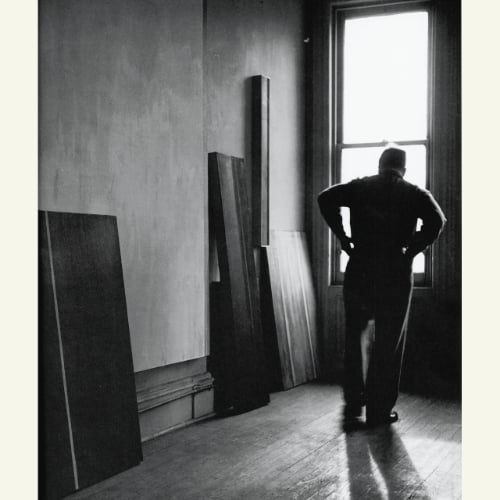

Barnett Newman, 1951. Photo: Hans Namuth © 1991 Hans Namuth Estate © 2013 Barnett Newman Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Barnett Newman complained that his wife Annalee didn’t understand that he was working when he was sitting in a chair looking out the window and smoking,” says Walter Robinson. “He’s my model.”

Studies have shown that creativity tends to occur when we’re not trying, which makes it important to let one’s mind occasionally drift from work. “In the summer, I go into the backyard and fiddle with the plants to remind myself about the cycles of the larger world,” says Rosler.

Like Newman and Robinson, Condo says he often finds himself just “sitting and staring.” When that gets old, he might “pick up a guitar or viola da gamba while the paint dries.”

“I rarely, rarely, make work on the weekend,” adds Buckman. “I need my weekends to be a mum, friend, human because there’s ample creativity in those roles and they need to be cultivated too.”

Shirin Neshat and her husband, writer Shoja Azari, collaborate on many projects. Photo by Slaven Vlasic/Getty Images.

We are only as productive as the people around us, social science shows, so it’s important to pick our partners wisely. “My first husband was domestically demanding,” says Tompkins. “My advice would be to have a partner who wholeheartedly supports what you do and respects both your time and your space to be alone.”

Neshat echoes this sentiment, saying that her husband and collaborator, Shoja Azari, is the first person she turns to when having a problem with her work: “He knows me and my work better than anyone I know, and he is usually super blunt and always very helpful.”

Selections from Shirin Neshat’s reading list.

“I read as much as I can because it helps me relax and escape my own work,” says Neshat. “I try to keep up with new writers. At the moment I am reading On Beauty by Zadie Smith and Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.”

Other artists look to history for inspiration. Childish reads Vedanã, “the ancient Indian path of self knowledge,” while Otero enjoys paging through rare, old exhibition catalogues.

“Lately I’ve been looking at the 19th century, fin de siécle, at the problems artists faced—in particular, women’s struggle—and noticing how much has changed and what has not,” says Liza Lou.

An artist at work. Photo by RODNAE Productions, public domain for Pexels.

Buckman is sensitive to jet lag, but when traveling from London to New York, she finds it can actually work in her favor. “I’m awake at dawn, will meditate, and then hit the studio for a few hours before anyone’s awake,” she says. “It feels really good in those moments and I have greater clarity. I feel kind of unstoppable but calm, and I often wish I could live my life on a rhythm like that.”

Billy Childish, in his studio. Courtesy the artist.

“I can paint and do interviews at the same time, as I don’t paint with that part of my brain,” says Childish. “When I go to paint I should obey the painting, not my wishes for the painting.”

“Whatever comes to mind is a good thing,” says Condo. “Don’t think before you work, work before you think.”