People

Lonely Days Can Make for Great Art. Here’s How 10 Artists Found Inspiration in Isolation, From a Bedridden Frida Kahlo to a Jailed Egon Schiele

Whether in imprisonment or exile, these artists channeled their isolation into creative fuel.

Whether in imprisonment or exile, these artists channeled their isolation into creative fuel.

Katie White

The myth of the solitary genius is being put to the test in 2020 as artists around the world are forced into isolation. Though undue pressure to create while on lockdown may be counterproductive (as the New York Times says, quit stressing!), artists of the past have noted the importance of uninterrupted concentration on productivity. “It seems to me that today if the artist wishes to be serious,” Edgar Degas once noted, “he must once more sink himself in solitude.”

We’ve heard about Shakespeare penning King Lear during the plague and Sir Isaac Newton developing calculus in quarantine. Throughout history, visual artists, too, have channeled experiences of confinement into artistic growth.

Here are 10 artists who found creativity during imprisonment, exile, and other periods of isolation.

Ruth Asawa holding a Form-Within-Form sculpture (1952). Photo Imogen Cunningham © 2017 Imogen Cunningham Trust, artwork © Estate of Ruth Asawa.

Ruth Asawa is famous for her enigmatic, almost mystical woven basket sculptures, which she likened to medieval chain mail. She went on to become a student of Josef Albers and an arts education advocate who spearheaded the creation of San Francisco School of the Arts. But before all that, the California-born Asawa had her earliest artistic experiences while she was a teenager interned in Japanese detention camps during World War II. First entering a camp in 1942 at the age of 16, she lived at the Santa Anita racetrack for five months before being sent to Rohwer, Arkansas, for her 18-month detention. Though she was forced to live in repurposed horse stalls and tar paper-covered barracks, the teenage Asawa nevertheless managed to find some inspiration by befriending several Disney cartoonists (also interned) who taught the artist the fundamentals of drawing. Reflecting on her experiences, Asawa remarked, “I hold no hostilities for what happened; I blame no one. Sometimes good comes through adversity. I would not be who I am today had it not been for the internment, and I like who I am.”

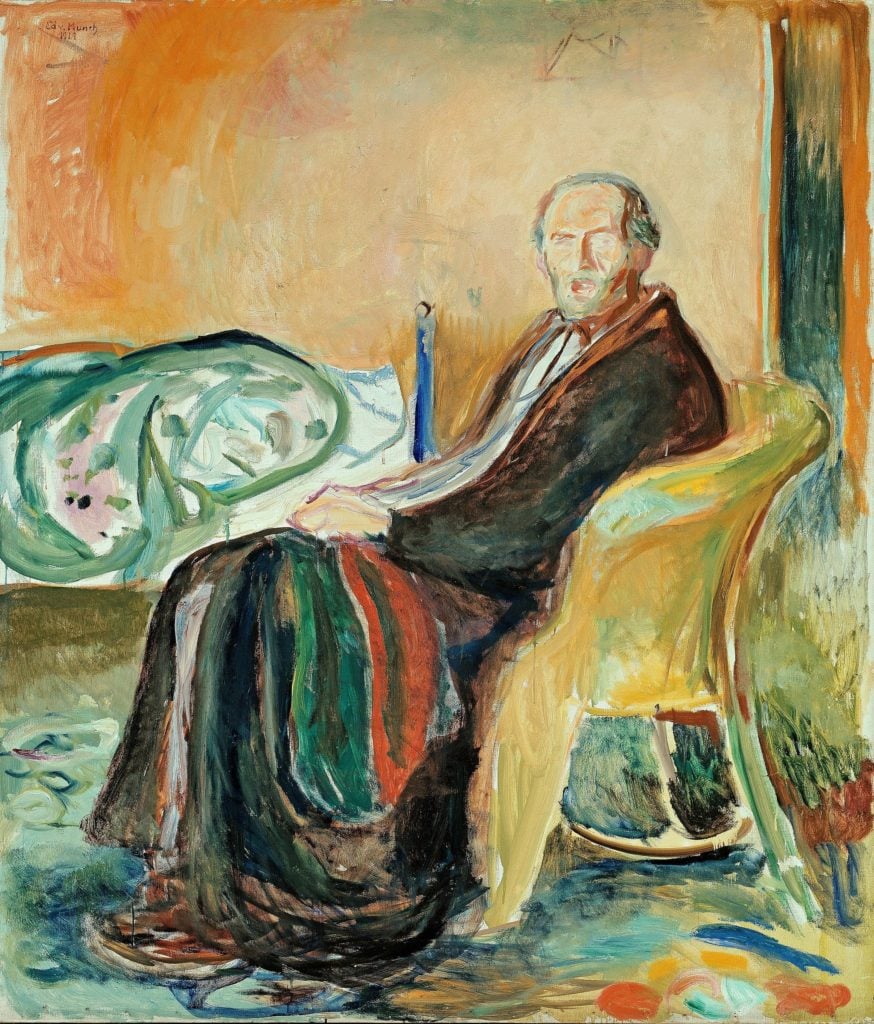

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu (1919).

Though many artists struggled to visually define the ravages of the Spanish Flu, Edvard Munch was not one of them. The painter of The Scream contracted the illness himself, and—with his known enthusiasm for the morbid—unsurprisingly turned his gaze to his own sickly likeness, painting Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu (1919), along with several other convalescent self-portraits. Munch, then in his mid-50s, seems to have had a more resilient constitution than he may have depicted. Unlike Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt, who are believed to have died from complications of the flu, Munch recovered and lived on some 25 years more.

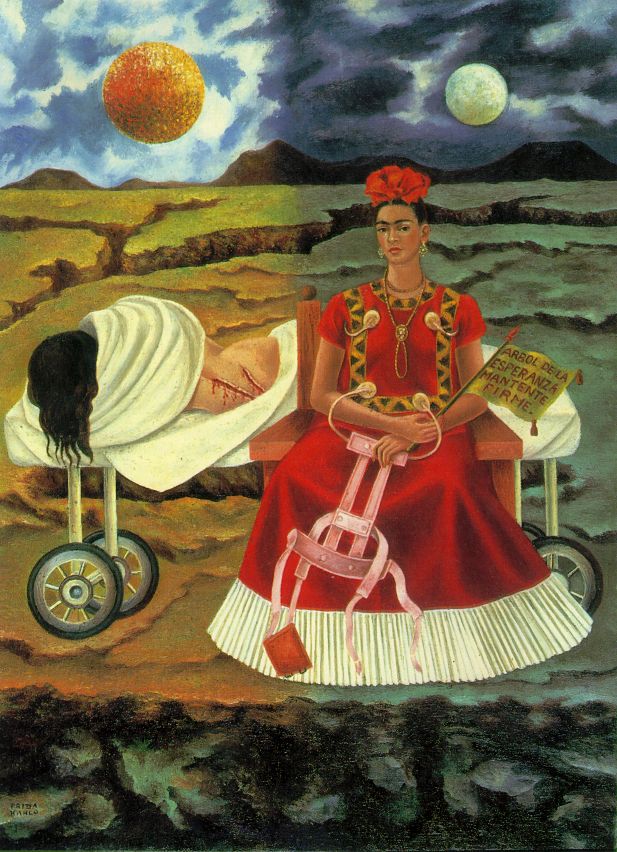

Frida Kahlo, Tree of Hope (1946).

Early in her life, Frida Kahlo suffered two significant physical traumas that would leave her confined to her bed for long periods. At the age of six, she contracted polio. The illness forever damaged her leg and caused her pain throughout her life. Then, 12 years later, as a student, she was severely injured when the bus she was riding on collided with a streetcar, hurling her from the vehicle and fracturing her spine and pelvis. Up until that point, Kahlo had planned to study medicine, but during her lengthy recovery, she turned her energies toward art. She painted her first self-portrait from her bed. Throughout her all-too-brief life, Kahlo would periodically become unable to leave her room due to illness; in order to adapt, she had an easel and mirror made for her bed, so she could continue painting.

Gülsün Karamustafa, Prison Paintings 6 (1972). Courtesy of the Tate.

A powerful voice in Turkey’s contemporary art scene, Gülsün Karamustafa creates works that weave together social-political commentary, autobiography, pop culture, and Turkish folklore through collage, costume, masks, and props (she first worked as a stage designer). During the 1971 Turkish coup, the artist was arrested and imprisoned for assisting political dissidents. After her release, and banned from leaving the country for 16 years, she painted her powerful “Prison Painting” series—15 works made from memory that depict tender, intimate moments in the lives of her fellow prisoners. “I made them in order to remember, in order to be able to keep [what happened] in mind,” the artist later remarked.

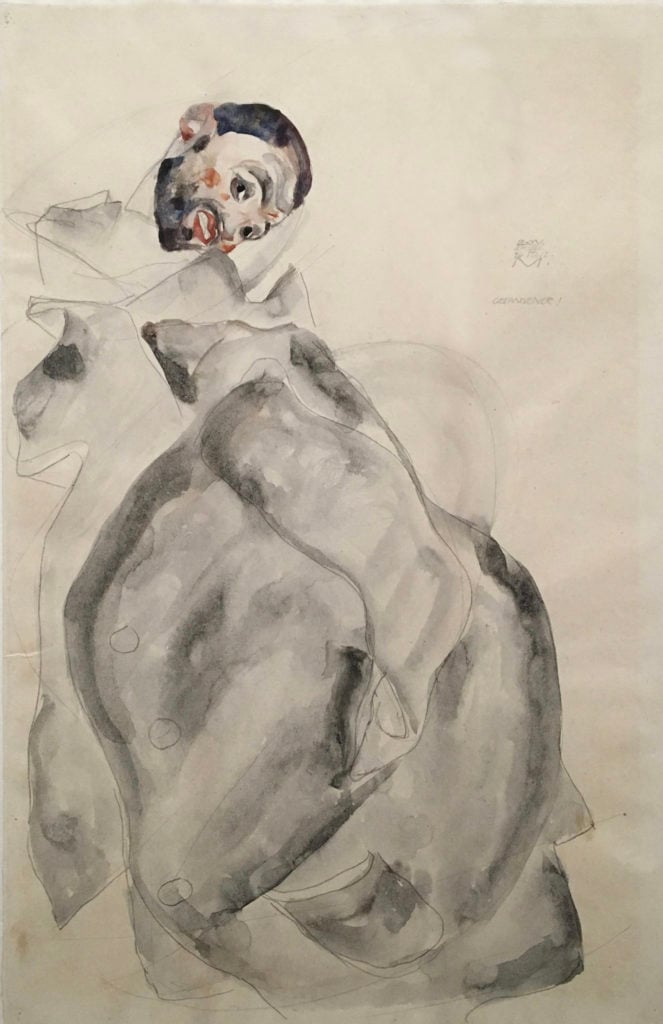

Egon Schiele, Prisoner! (April 24, 1912). Courtesy of the Albertina.

Egon Schiele lived an unconventional lifestyle both by the standards of his time and ours. He and his teenage mistress and muse Wally were often ostracized as they moved throughout Austria. But it was Schiele’s emaciated, contorted, and unflinchingly sexualized portraits that most scandalized the public. In April 1912, that discomfort boiled over when Schiele’s home and studio were ransacked by local constables on the hunt for evidence of immorality. More than 100 of Schiele’s drawings were seized and the artist was imprisoned for 24 days while awaiting trial on charges of pornography.

Schiele’s imprisonment proved to be perhaps the most profound and emotionally damaging event in the artist’s short life, but he channeled his sentiments into his “Prison Drawings”—a series of psychologically raw compositions that are considered among the most important of his career. Though Schiele was ultimately cleared of the charges against him, he was nevertheless sentenced to an additional three days’ imprisonment following the trial for “failing to keep erotic nudes in a sufficiently safe place.”

![Barbara Ess, Fire Escape [Shut-In Series] (2018-2019). Courtesy of Magenta Plains.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2020/05/be_040-2-993x1024.jpg)

Barbara Ess, Fire Escape [Shut-In Series] (2018-19). Courtesy of Magenta Plains.

In 2018, Ess found herself holed up in her apartment with a bad case of bronchitis that lasted for over a month. With a much smaller (and literal) creative aperture, the artist turned to the views from her apartment and the small details of her daily domestic sphere. With that, her “Shut In” series was born—a set of small prints Ess marked up with silver, black, and white crayons and later scanned and enlarged.

Joseph Beuys, I Like America and America Likes Me (1974).

Photo: Joseph Beuys.

In 1974, Joseph Beuys brought the call of the wild indoors with his performance I Love America, and America Loves Me. For three days, the German-born artist lived in a New York gallery with a wild coyote. Beuys considered the coyote the embodiment of untamed American individualism and the confinement was intended as the artist’s symbolic reconciliation with nature. Surprisingly—and after a period of tearing at Beuys’s unusual felt vestment—the animal became tolerant of the artist’s presence, even accepting a hug at the end of the performance.

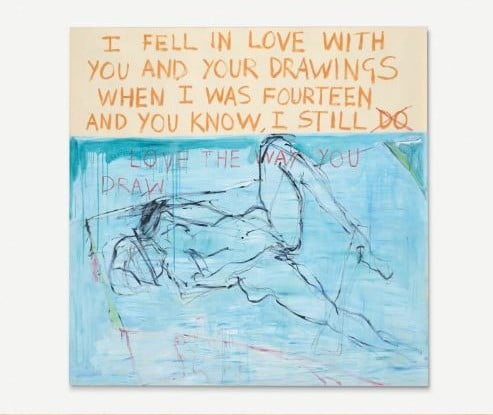

Tracey Emin, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made (1996). Courtesy of Christie’s.

Upping the ante on gallery quarantines, in 1996, YBA Tracey Emin set herself up in a locked Stockholm gallery for two weeks with nothing but a batch of blank canvases and her art supplies. Stark naked (we’re not sure why), Emin could be seen furiously creating through a set of wide-angle lenses installed on the gallery walls. First delving into imagery inspired by artists she loved (Schiele, Munch, Yves Klein), Emin eventually worked through their legacies to arrive at her own deeply autobiographical visual language. The project, called Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made, resulted in 12 large-scale canvases, seven body paintings, and 79 drawings and sketches—and would prove to be one of the most significant milestones in her career. The body of work sold at Christie’s in 2015 for £722,500.

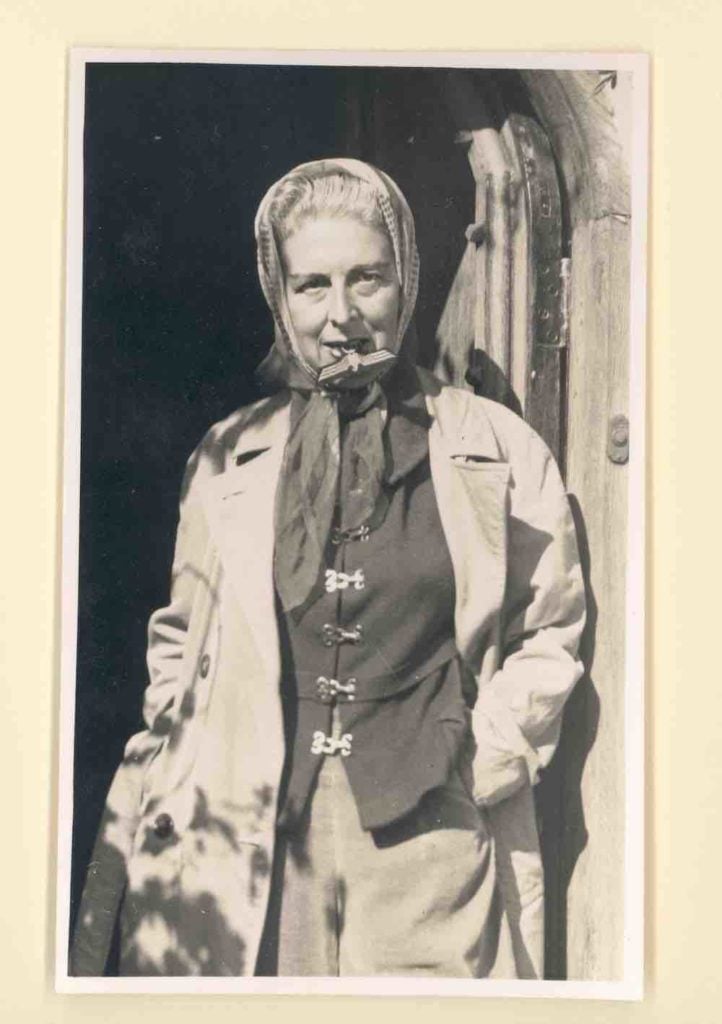

Claude Cahun, Self-Portait (1945).

Stepsisters, lovers, and avant-garde artists Claude Cahun (born Lucy Schwob) and Marcel Moore (born Suzanne Malherbe) sought out isolation—but it didn’t go quite as expected. Facing increased anti-Semitism in Paris (Cahun’s father was Jewish), the pair moved to Jersey in the Channel Islands off of England in 1937, but by the end of the decade it became clear to all that the Nazis would take control of the area. Though many inhabitants fled, Cahun and Moore decided to stay, and—under a military lockdown that lasted from 1940 to 1944—staged Dada-inspired interventions intended to create dissent within German military ranks. (Cahun would dress as a man and sneak notes about the absurdity of war into soldiers’ uniform pockets, for instance.)

When the two were eventually found out and arrested in 1944, Nazi officials had a hard time believing that they had managed the widespread campaign alone. In their 50s at the time, Cahun and Moore were sentenced to death, but the punishment was never carried out. Though they were ready to be martyred for their cause, the lifelong companions would go on to create role-playing, gender non-conforming artworks until the end of their lives. One particularly remarkable photographic self-portrait from 1945 shows Cahun clenching a Nazi eagle badge between her teeth.