People

7 Scientific Pioneers Who Were Also Artistic Visionaries, From the Inventor of the Morse Code to the Founder of Neurobiology

Who says you can only have one calling?

Who says you can only have one calling?

Katie White

Art and science are often thought to fall on opposite sides of the left-right brain divide, but history has proven time and again that many of the brightest minds are polymaths.

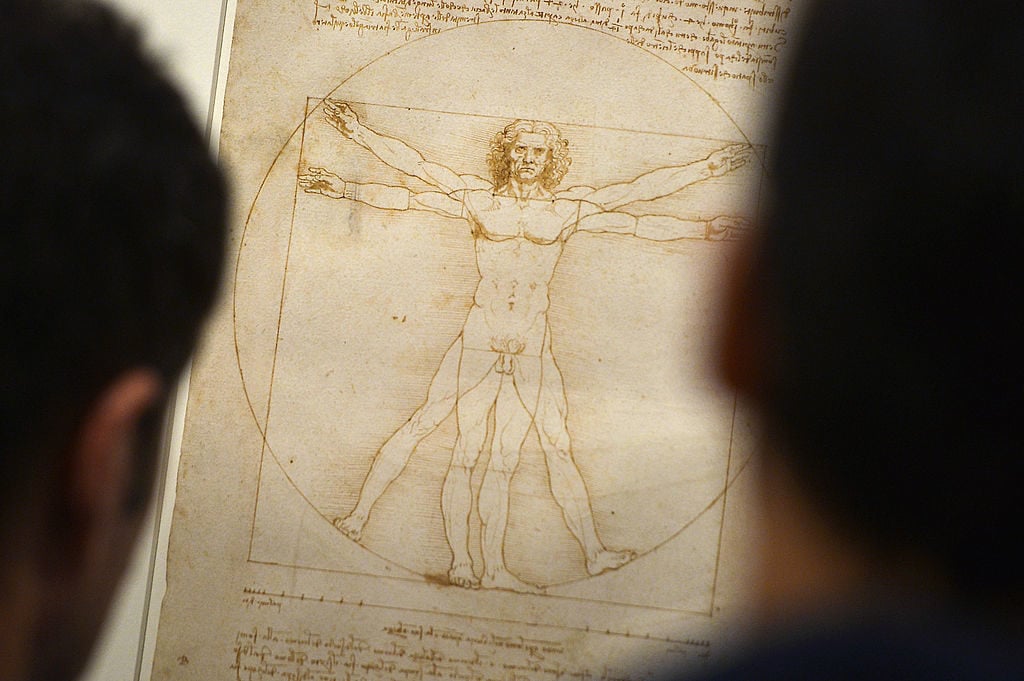

Leonardo da Vinci, the greatest of all the artist-scientists, once wrote, “To develop a complete mind: Study the science of art; Study the art of science. Learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.” His suggestion is being taken even today, with many medical schools requiring soon-to-be doctors to take art and art history classes, while contemporary artists including Trevor Paglen, Anicka Yi, and Neri Oxman find influences in astronomy, biology, and geology.

From adventuring woman botanists to the drawing-enthused father of modern neuroscience, learn more about art history’s great scientific minds below.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Caterpillars, Butterflies (Arsenura armida) and Flower (Pallisaden Boom: Erythrina fusca), Plate 11 from Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (1705). Collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, public domain.

Scientific Contributions: A 17th-century naturalist and botanist, Merian was one of the first European scientists to directly observe insects. When she started her research, insects were still commonly referred to as “beasts of the devil” and were thought to spontaneously generate from mud. Her most influential studies detailed the metamorphosis of caterpillars into butterflies—a phenomenon that was largely undocumented before her investigations. She penned a two-volume book on caterpillars, with each accompanied by 50 plates of engravings, and is today considered one of the pioneers of the field of entomology.

Artistic Pursuits: Before her scientific investigations, Merian first earned acclaim as a botanical artist, publishing a three-volume series, each of 12 illustrated plates of flowers, in 1675. As was common at the time, these decorative illustrations, which were not drawn from direct observation, were intended to be used by upper-class ladies as designs for embroidery, drawings, and paintings. Merian’s interests extended far beyond the parlor, however; an adventurer to the umpteenth degree, she traveled to Dutch Surinam on a self-funded journey in 1699 (raising many eyebrows) and documented a wealth of flora, creating some of the first color illustrations of the New World.

Samuel F. B. Morse, Gallery of the Louvre (1831–33). Courtesy of Terra Foundation for American Art,

Scientific Endeavors: As a student at Yale, Samuel Morse studied philosophy and math, but dreamed of a career as an artist of great history paintings. After that dream cooled, he went on to pursue his interest in the burgeoning field of electromagnetics—and for the future of telecommunications, his shift in studies was a godsend. Morse would go on to develop both the telegraph and the Morse code, absolutely dazzling the world when, on May 24, 1844, he sent the biblical line, “What hath God wrought?” from the US Capitol in Washington, DC, to Baltimore, with his new invention.

Artistic Pursuits: Though his career in the arts was overshadowed by his stunning accomplishments in the field of communications, Morse made a serious go at art, studying under the painter Washington Allston, and then with Benjamin West at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Large-scale Neoclassical paintings of myth and history scenes were his passion, and the most famous of his works is the monumental Gallery of the Louvre, measuring an impressive six by nine feet. Returning to the United States, he found the American public unreceptive to his style, which he blamed on a culture of prevailing bad taste.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Lucybelle Crater and her 45-year-old husband’s photo-Bell friend’s sonshine, Lucybelle Crater (1970-72). Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery.

Scientific Endeavors: Ralph Eugene Meatyard extended both of his careers, as a photographer and an optician, from a scientific and philosophical fascination with light and vision. Born in Normal, Illinois, Meatyard served in the military before becoming a licensed optician in 1949. A position with an optical firm would bring him to Lexington, Kentucky, in 1950. This firm also owned a photography company, which introduced the doctor to the medium. Profoundly influenced by Zen Buddhism (and a pen pal of the Trappist monk Thomas Merton), Meatyard would spend some three months looking through an unfocused camera to attain what he called a state of “No-Focus,” in which the appearance of an object was detached from its meaning.

Artistic Pursuits: Meatyard began taking photographs in the 1950s and would pursue the practice until his early death in 1972. His photographs were unusual for the time, and often included blurred figures, and, later, portraits of his children and himself wearing odd, monster-like masks. Meatyard earned little critical acclaim in his lifetime, though his works was presented alongside those of Ansel Adams, Aaron Siskind, and Harry Callahan in “Creative Photography,” an exhibition curated by Van Deren Coke for the University of Kentucky. His peculiar style often left him relegated to a regional style of Southern Gothic, though his posthumously published photo-book, The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater (named after the main character in Flannery O’Connor’s short story, “The Life You Save May Be Your Own”), earned him increasing institutional attention.

Anna Atkins, (clockwise from top left) Peacock (1861), Laminaria phyllitis (1844–45), Papaver rhoeas (1861), and Alaria esculenta (1849–50). Courtesy of Hans P. Kraus Jr., New York (top left and bottom right); the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Scientific Endeavors: This English botanist Anna Atkins was fascinated by the delicate and diverse varieties of algae to be found in the waterways of Great Britain. In 1843, Atkins published the first half of her scientific reference book, British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, using light-sensitive materials to capture her specimens, thereby establishing photography as a scientific tool.

Artistic Pursuits: Atkins is regarded as the first person to publish a book illustrated with photographs and is considered by some to be the first woman to create a photograph to begin with. Moreover, she learned about the photographic process directly from her frequent correspondent Henry Fox Talbot, the man who invented the salted paper and calotype processes, the precursors to modern film photography.

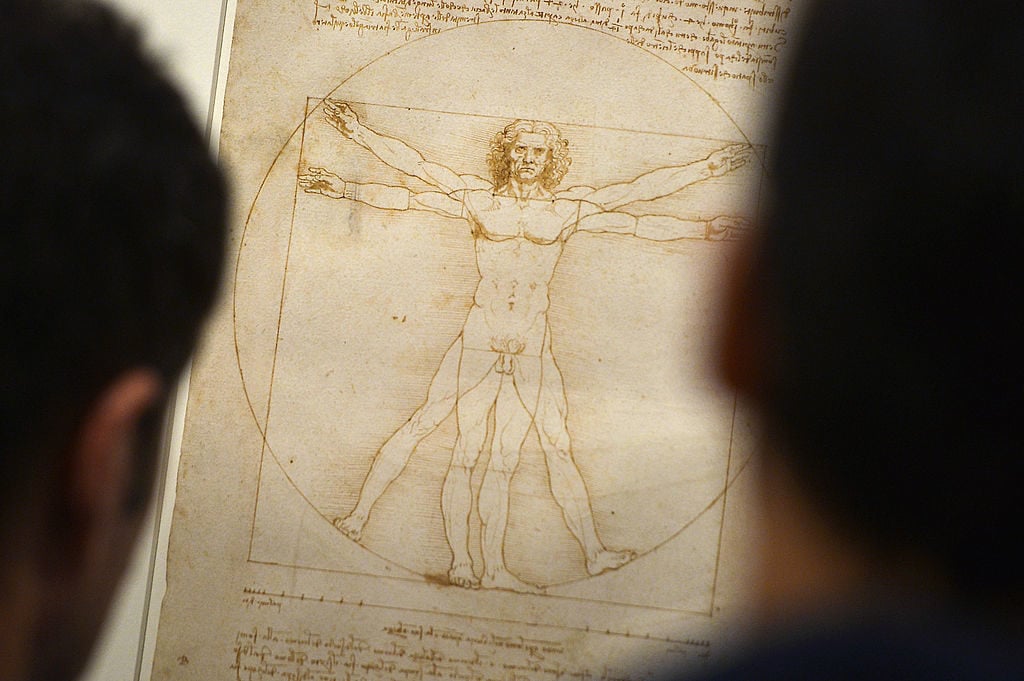

Leonardo da Vinci’s aerial screw design, from folio 83-verso of the Paris Manuscript B. Collection of the Institut de France.

Scientific Endeavors: A true Renaissance man, Leonardo da Vinci was fascinated by anatomy, botany, astronomy, and geology, among an unending litany of other fields. Today he is best remembered for his artistic accomplishments, but his contributions to science were revolutionary and wide-reaching. He posited that the earth was not the center of the sun’s orbit and dissected bodies to learn the inner workings of organs and human bone structure. His notebooks are filled with inventions that could not be realized in his lifetime, including the parachute, helicopter, and even the calculator.

Artistic Pursuits: Da Vinci believed that art, science, and nature were inextricably linked and could not be fully be appreciated except in synthesis—and his contemporaries and later followers seemed to agree. His paintings the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper still draw unbelievable crowds, and his sketch of the Vitruvian Man, another cultural touchstone, is perhaps the best representation of his belief that scientific study could reveal harmony and proportion in the universe.

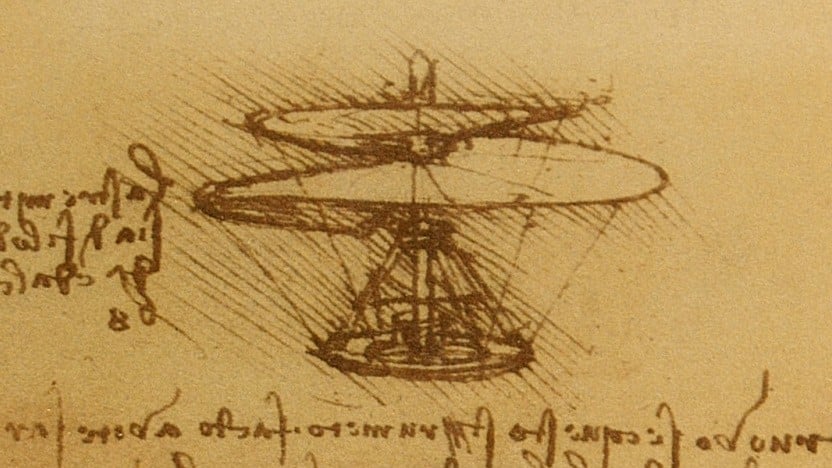

Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s Calyces of Held in the nucleus of the

trapezoid body (1934). Courtesy of Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid.

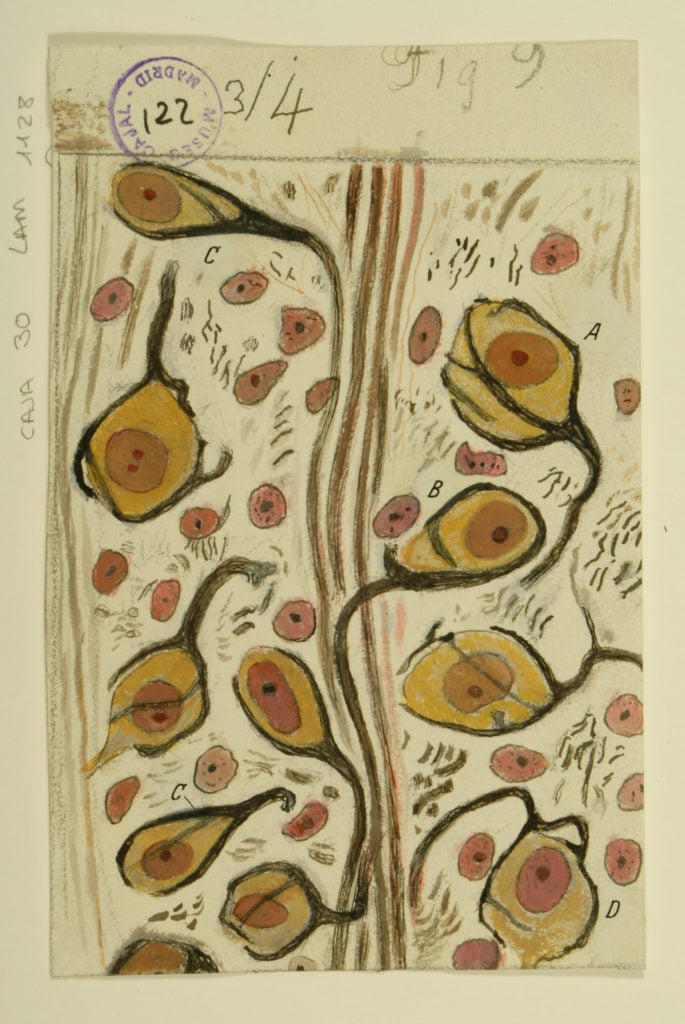

Scientific Contributions: The Spanish-born Cajal has been called the father of modern neuroscience, and in 1906 won the Nobel Prize for his revolutionary research into the nervous system. He was the first person to suggest that the brain is composed of individual cell structures, and his contributions to the understanding of how the brain actually works are still studied today.

Artistic Pursuits: Cajal aspired to be an artist before his father encouraged him to pursue medicine, but his initial passion never waned. During his career, he made thousands of detailed drawings of brain matter based on what he saw through microscopes, and today these drawings remain valued sources for neurological study. His images range in style from Vienna Secession-inspired tree-like branches of the nervous system to inky, amorphic images of neurons.

John James Audubon, American Flamingo from The Birds of America. Courtesy of the Field Museum, Chicago.

Scientific Endeavors: Ornithologists around the world revere his name to this day. John James Audubon was born in Haiti and raised in France, then immigrated to Pennsylvania at the age of 18. His love of birds translated into an impassioned and scientific pursuit, as he studied their migratory habits and depicted them realistically in their habitats. He traveled the US endeavoring to depict all the birds in the county and was America’s leading wildlife artist for half a century. The Audubon Society is named after him and is inspired by his mission.

Artistic Pursuits: Audubon’s depictions of birds were far from purely scientific. He depicted his creatures with delicacy, color, and often bits of flora for their habitats. His Birds of America, a collection of 435 life-size prints, remains the standard for wildlife artistry. An early copy of the mammoth book sold for $11.5 million at Sotheby’s in 2010.